Reality bites: From Mideast to Congress, Biden's next hundred days are harder. Now what?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

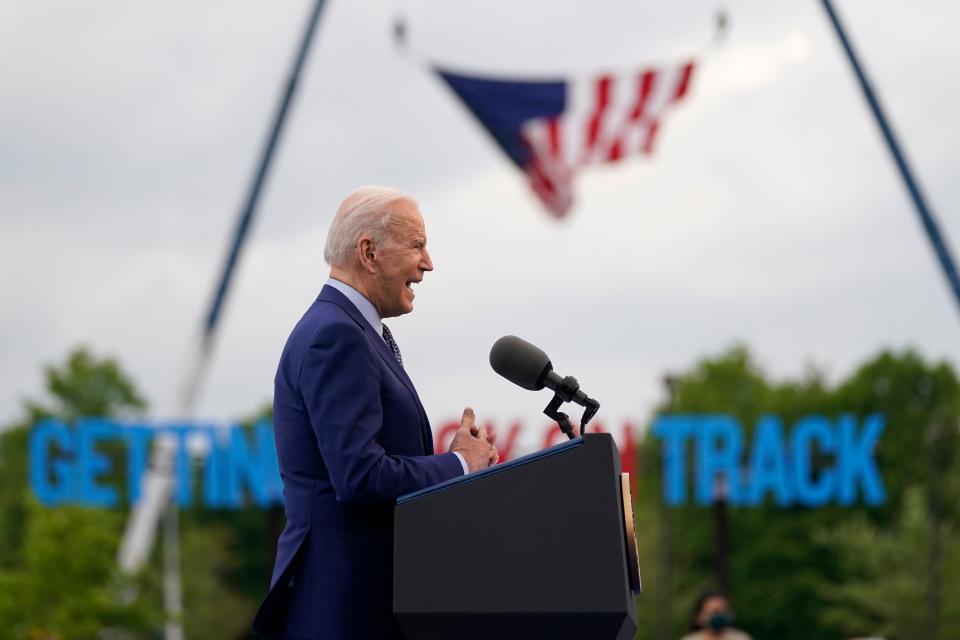

For President Joe Biden, the second 100 days are turning out to be harder than the first.

After a sure-footed start in office focused on the priorities he chose – controlling the pandemic and reviving the economy – Biden last week found himself pulled into the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, a long-running problem he probably can't fix but also can't ignore. White House negotiations with Republican senators on a signature infrastructure bill stalled, a test of the bipartisanship he has promised. Prospects evaporated that Congress could meet Biden's deadline to pass a police reform bill by Tuesday, the one-year anniversary of George Floyd's murder.

And Democrats on the left, largely supportive of the administration so far, made their first big break with the White House, demanding the president do more to confront Israel and protect the Palestinians.

It's the lesson his predecessors in the White House also learned: Sooner or later, reality bites.

The first 100 days:Why Joe Biden's presidency has been so surprising

In their early months in office, presidents are always at risk of being tested by foreign adversaries, challenged by the partisan opponents in Congress and sidetracked by crises of all sorts. Unexpected developments can redefine a presidency in an instant, as the 9/11 attacks did for George W. Bush during his first year in office, or distract presidents from the course they intended to chart, a problem that bedeviled Bill Clinton at the beginning.

Now conflicts and calamities are testing whether Biden has the ability to address them – and the agility to prevent them from overwhelming the causes he wants to pursue.

The former Delaware senator and two-term vice president has had a long time to watch how commanders in chief swim, or sink, in roiling waters. Elected to Congress when Richard Nixon was in the White House, he has seen nine of them up close.

"As you’ve all observed, successful presidents, better than me, have been successful in large part because they know how to time what they’re doing — order it, decide and prioritize what needs to be done," Biden told reporters at his first White House news conference. At that moment, he was holding back demands from activists that he do more, and act faster, to address gun violence, immigration and other issues.

But timing isn't always under a president's control. By Aug. 8, when his second 100 days expire, here are three big questions Biden will have to face:

1. Is it time to give up on bipartisanship?

Bipartisanship scored a victory last week, with the president signing into law a measure aimed at curbing the rise in hate crimes against Asian Americans in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. The closely divided Congress easily passed it.

But there was a bigger defeat on the horizon. While the House approved legislation to establish a 9/11-style commission to investigate the historic storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6, supported by every Democrat and 35 Republicans, the Senate seems increasingly unlikely to produce the 10 Republican votes needed to overcome a filibuster against the proposal.

Related: Capitol Police union warns of departures after Jan. 6 riot and continued overtime strain

What's more, White House talks for a massive infrastructure bill hit a pothole, or perhaps smashed into a roadblock. Republicans on Friday scoffed at the administration's offer to cut the bill from $2.25 trillion to $1.7 trillion – still a breathtaking number, albeit a smaller one. West Virginia Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, the GOP's lead negotiator, said the two sides were moving further apart.

They have not yet agreed on how much to spend, what to spend it on or how to pay for it. Indeed, they haven't been able to agree even on how to define "infrastructure."

Some skeptics, especially on the left, argue Biden is just wasting time, that Republicans aren't negotiating in good faith. "We would like bipartisanship," Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders said Sunday on CBS' "Face the Nation," but he added, "If they aren’t coming forward, we've got to go forward alone."

Going it alone means using a parliamentary device known as budget reconciliation, which limits the provisions that can be included but also averts the threat of a filibuster.

Cedric Richmond, a senior White House adviser who until a few months ago was a member of Congress himself, on Sunday acknowledged that day could arrive for Biden. As long as "there are meaningful negotiations going, taking place in a bipartisan manner, he's willing to let that play out," Richmond said on CNN's "State of the Union." "But, again, he will not let inaction be the answer. When it gets to the point where it looks that is inevitable, you will see him change course."

That said, winning without any Republican support means holding every Democratic vote in the Senate and almost every Democratic vote in the House.

2. Can Democrats stick together?

The Democratic margins in Congress could hardly be narrower. The Senate is split 50-50, with only Vice President Kamala Harris' tie-breaking vote giving Democrats control. The House is divided between 219 Democrats and 211 Republicans, the narrowest margin in modern times. (Five seats are vacant.)

Do the math: In a partisan-line vote, Republicans could block a Democratic initiative by gaining the support of just four Democrats.

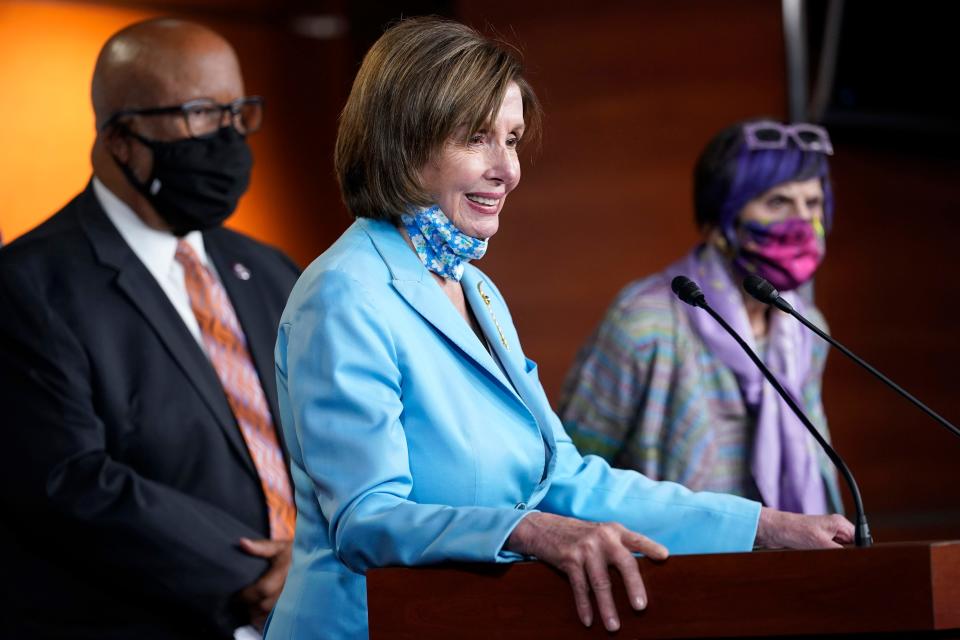

That nearly happened Thursday, when Speaker Nancy Pelosi narrowly avoided what would have been a stunning defeat. Three progressive Democrats voted against a $1.9 billion bill to bolster security at the Capitol. Reps. Cori Bush of Missouri, Ilhan Omar of Minnesota and Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts complained that the bill would provide funding to increase police surveillance and force without addressing systemic problems of racism and misconduct.

The measure managed to pass but only because three other progressives often aligned with them agreed to vote "present" rather than "no." They were Reps. Jamaal Bowman and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan.

In the end, the Democratic bill slipped through, 213-212. But the legislative scramble and the single-vote victory was a reminder of the challenge of holding the disparate Democratic caucus together, a task that is likely to only get more difficult as the midterm elections approach.

3. Is the economy taking off, or faltering?

No development will have more impact on passage of Biden's major legislative priorities now and on Democratic prospects in the midterms next year than the state of the economy.

While the economy at the beginning of the year seemed poised to take off as the pandemic eased, warning flags are raising concerns about jobs, growth and inflation. In April, the economy created only 266,000 jobs, far short of the 1 million expected. A cyberhack of Colonial Pipeline sparked a brief fuel shortage and spike in gas prices in the Southeast. Some economists, including Larry Summers, a former Treasury secretary for President Barack Obama, caution that Biden's huge spending proposals risk overheating the economy.

“When we came into office, we knew we were facing a once-in-a-century pandemic and a once-in-a-generation economic crisis," Biden said when the disappointing jobs report was released. “We knew this would not be a sprint, it would be a marathon."

Within the next few weeks, metrics including the May jobs report and second-quarter GDP will indicate whether the weak jobs report was a blip or a warning, whether inflation is a significant concern, and whether growth is on track.

Because for presidents, everything tends to be easier during booms, and everything harder during busts. During the second 100 days. Or anytime.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Biden's plans interrupted by Mid-East conflict, Republicans, economy