What Really Happened to Baby Christina?

At around 7:00 a.m. on June 16, 1998, Barton McNeil, a thirty-nine-year-old divorced father, woke up on the couch after a muggy, stormy night. It was the beginning of one of those long summers in Bloomington, Illinois, the air so heavy you could chew it.

The evening before, he and his girlfriend, Misook Nowlin, had broken up. They’d gone out to Avanti’s, a local Italian restaurant, and gotten into it yet again. The previous year, Nowlin had been convicted of domestic battery against McNeil, and he was due in court the next day to testify at her sentencing hearing.

Nowlin wanted McNeil to speak on her behalf, and at first he’d planned to. Even though he’d testified against her at trial, he felt sorry for her and didn’t want her going to prison. But at the restaurant his feelings had changed. She’d confessed that jealousy had driven her to snoop around his garbage and his phone records, convinced he was having an affair. He ended the meal early and left, furious. Besides, it was his night with his three-year-old daughter, Christina, and he had to pick her up at his ex-wife’s house.

Mulling the fight over in the morning, McNeil couldn’t shake the image of Nowlin trembling with anger as they paid the check, or of her pleading with him to talk it through as he rushed from the restaurant. She’d even followed him out of the parking lot. When he stopped the car and demanded to know what she was doing, she said she wanted to warn him his tailpipe was smoking.

McNeil, medium height, lanky, and balding, stretched out on the sofa and felt his lack of sleep—after the fight, he’d been up late online chatting with a woman in the Philippines. Now he heaved himself upright and stumbled to his desk to check his email. Nothing of interest.

McNeil traipsed to the bathroom and called out to wake Christina in the bedroom next door. It was time to get up and get dressed. She didn’t stir. McNeil, a prep cook at the nearby Red Lobster restaurant, had less than an hour to drop Christina off at daycare and get to work.

He smoked a cigarette on the toilet and called to Christina one more time. Still nothing. So he took a shower, then checked his email again, and finally crept into the bedroom. There she lay, wrapped in the swirl of her flower-patterned sheets, a copy of Go, Dog. Go! beside her. Her eyes were open, her skin clammy and the color of slate.

McNeil froze. His stomach churned. Panic took the wind out of his lungs.

He scrambled for the phone and dialed 911.

“911, what’s your emergency?” answered the dispatcher.

“I need an ambulance! I need it fast. 1106 North Evans. My daughter is dying...” McNeil wheezed.

The dispatcher’s voice was monotone. “Okay... you got to help me out here now.”

McNeil whimpered in agreement.

“Try to stay calm. How old is your daughter?”

“Three.... I think she’s dead!”

McNeil attempted CPR, but blowing into Christina’s mouth made a hideous, whining sound; blood ran from her nose, and her body sagged in his arms. “It’s Christina, it’s Christina, it’s Christina!” he howled. “Ohhhhhh, Christina!”

The paramedics arrived minutes later, and McNeil sank to the kitchen floor, stupefied. They shouted instructions to each other over the thud and clatter of their work. Patrol officers trampled through the living room. McNeil could still see Christina lying in his Red Lobster T-shirt and her white underpants with the word MONDAY written across them.

Paramedics remember him wailing, “frantic,” but that they saw “no tears.” When officers asked him for the number of Christina’s mother, his ex-wife Tita McNeil, he had trouble remembering it, even though he called her home almost daily.

According to police, when she eventually arrived, she screamed at McNeil, “What did you do to my child?” (McNeil does not recall this.) She then crouched next to Christina’s limp body and began stroking her daughter’s arm. McNeil sat beside her, staring, disconnected, disbelieving.

Just after 9:19 a.m., the coroner’s office removed the girl’s body from the apartment. Less than fifteen minutes later, believing they’d seen nothing suspicious, the police released the scene.

The place was empty. Friends had taken Tita away, and the authorities were gone. McNeil sat on his porch smoking cigarette after cigarette. How could he go back inside and face the things Christina had left behind? Her nebulizer. The book she had been looking at the night before. The tiny white dress hanging on his bedroom door that she would have worn that morning to daycare.

From the front porch, McNeil thought he saw—could it be her?—Nowlin. She’d shown up earlier that morning while the police were there and he’d asked her to leave. Now she was back. Nowlin pulled over a few doors down from McNeil’s home and approached him. She was cold and matter-of-fact, which wasn’t at all like her. But the strangest thing of all came next: McNeil claims she said, “Well, could Christina have been murdered?” (Nowlin denies having said this.)

After a brief conversation, which Nowlin says took place inside but McNeil insists happened outside, she left for work, as if nothing unusual had happened.

McNeil was confused. Had Christina been murdered? What was Misook saying? But he was also anesthetized by shock, unable to think straight. And, anyway, he couldn’t stand to be at the apartment any longer, so he headed for the home of his ex-wife, Christina’s mother, the only person in the world who he trusted was in as much pain as he was. But he found little respite there. His mind kept returning to the breakup and the hours after. Why had Misook called him last night, asking if he was home with Christina and where she was sleeping? (Phone records confirmed that Nowlin called McNeil that night, but she later said she could not remember the call.) Why had she arrived unannounced that morning and stayed until after the police left?

Could Misook have killed Christina?

McNeil’s mind raced. It wasn’t likely that anyone entered the apartment through the front door; he was sleeping on the sofa next to it. Besides, anticipating that Nowlin might return wanting to keep arguing, McNeil had secured the screen door the night before, which he didn’t usually do.

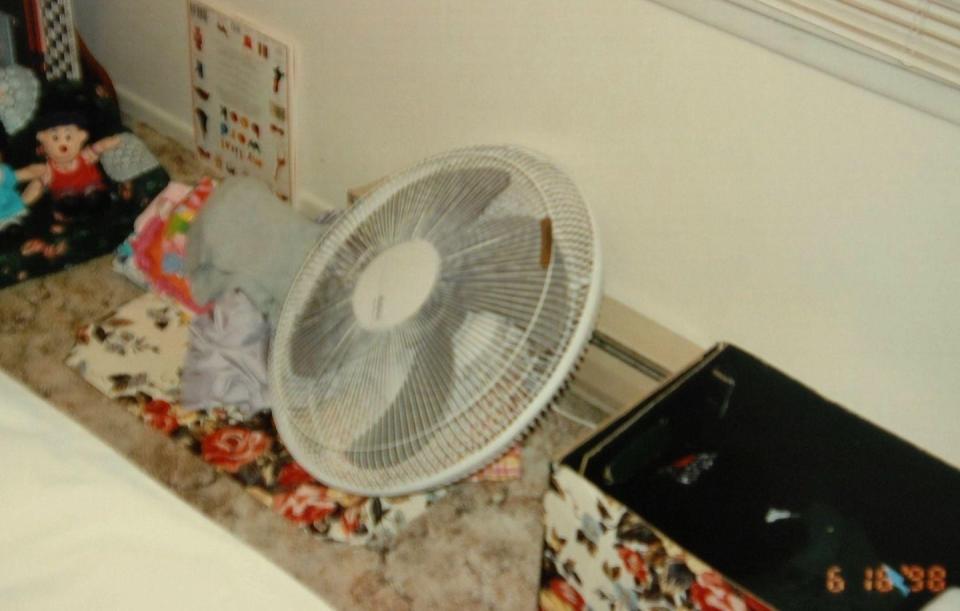

He could only imagine that she might have entered through Christina’s bedroom window. Come to think of it, there had been something off in Christina’s room that morning. He just couldn’t figure out what.... The fan. When he entered Christina’s room that morning, it had been on the floor, not mounted to the window, where it had been most of the spring. But, McNeil thought, to get to the fan, the killer would have to first get past the latched window screen. Opening the screen from outside would be impossible without damaging the window.

McNeil excused himself from Tita’s and returned to his home on North Evans Street. He walked up a narrow cement path lined with bushes and messy shrubbery, toward the window of Christina’s bedroom. He saw holes in the storm screen’s lower corners, and the screen appeared completely off its track.

At 5:16 p.m., ten hours after he’d found Christina dead, he called 911 again. “My name is Bart McNeil,” he told the dispatcher. “My daughter was found dead by me this morning at this address. The detectives were here, the coroner, everything. I need a detective—the homicide detective. I have reason to believe she was murdered....”

In the late nineties, the twin cities of Bloomington and Normal were a good place to grow up and raise a family, in a white-picket-fence sort of way. The cities are in the middle of the state, about halfway between Chicago and St. Louis, with brightly colored Victorians lined up quietly and politely. Some of the streets are cobbled. In the 1990s, the cities had such a low murder rate that the Bloomington police had no dedicated homicide department.

In fact, when McNeil made his second 911 call, the officers were in such disbelief at his story that the shift lieutenant sounded annoyed. McNeil kept calling and calling, insisting that they investigate a murder. “What the hell’s his problem?” the lieutenant snapped at the dispatcher.

A detective arrived at McNeil’s home nearly forty-five minutes after his first call that afternoon. McNeil waved him down from the sidewalk outside his home and showed him the window screen. McNeil told the detective that he thought Nowlin had done it and that she had killed his daughter. He was almost hyperventilating as he spoke.

The detective sent McNeil to the police station to be interviewed. The detective would stay behind to meet the crime scene technician who had been there in the morning. When the technician arrived, he said he’d seen a hole in the screen that morning, but just one. He later reported that he’d also noticed spiderwebs connecting the window frame to the screen.

At the police station, McNeil recounted the previous night: After leaving Nowlin, he reached his ex-wife’s place at about 7:00 p.m. to collect Christina. She hadn’t had dinner, so McNeil drove her to McDonald’s for a Happy Meal and then home. By 10:30, McNeil had begun the bedtime routine, and fifteen minutes later, Christina was tucked in.

McNeil then logged on to his computer and chatted with the woman from the Philippines until around midnight, when he said he heard a voice coming from Christina’s room. He found his daughter sitting up in bed, grinning. He tucked her in once more.

A little before 2:00 a.m., McNeil crashed on the couch after a last peek at Christina. The rumble of a brewing thunderstorm kept him awake until about 2:45 a.m.

McNeil was more interested in getting the detectives to understand his theory than in explaining his routine. He insisted they look at Nowlin. She was obsessive, he claimed, capable of violence, and even “maniacal.” The night before, she’d been apoplectic during their breakup. Killing Christina must have been some sort of revenge, McNeil asserted. Still, as he drove home that night, he felt that his theory had fallen on deaf ears.

McNeil returned to the police station the next day. In his only recorded interview with the police—despite his insistence that everything be recorded—he was combative from the start. He criticized the police work: “My only daughter is lying on a cold-ass slab of concrete, and you guys are sitting on your ass. I want that fucking forensics team down there now!” he shouted at one point.

Detectives also interviewed Nowlin, who said she’d gone home after the fight at Avanti’s and was later joined by friends. Around 8:00 p.m., they ventured out to a local pool hall and stayed until about 9:30, when Nowlin returned home with her friend Susie Kaiser. The pair stayed up gossiping and eating Korean food for at least another ninety minutes. The topic was McNeil: The breakup had left Nowlin shattered, sad, and angry. “I really love him,” she told detectives. Kaiser said Nowlin had told her she wanted to visit McNeil that night; she advised against it.

After Kaiser left, phone records confirm that Nowlin received a call at 12:21 a.m. She’d hoped it was McNeil. She was desperate to talk to him. Instead, it was her brother in Korea on the line, and they only spoke for sixty-two seconds. Nowlin claimed she fell asleep, exhausted and disappointed. She didn’t wake until her ex-husband Andy Nowlin came around to drop off clothes for their daughter about 6:00 a.m. (Andy Nowlin corroborated this visit but said he went to pick the clothes up, not to drop them off.)

In a separate room, things were not going well for McNeil. He kept referring to himself as a “suspect” and insisted that police should “arrest him [rather] than arrest nobody at all.” He said, “Even though I don’t know the autopsy [results], I already know what they are: died by asphyxiation.”

The timing of that comment couldn’t have been worse for him. Later that morning, Dr. Violette Hnilica, the forensic pathologist, released the autopsy results: Christina had died from smothering. Dr. Hnilica identified swelling of the vagina and anus. She suspected sexual molestation.

Later that day, investigators interviewed McNeil again, this time for some eight hours. No recordings or transcripts of this interview are available, just police narratives summarizing the event, and the Bloomington Police Department did not reply to questions about its investigation. But according to those summaries, the police found McNeil’s claims impossible. There were spiderwebs on the window frame, for one, and it had stormed the night before, for another. An intruder surely would have left muddy footprints, but the carpets in the apartment had all been dry.

In the investigators’ view, Christina and McNeil were together inside a locked residence and there was no evidence that anyone else had been there that night. McNeil must have killed Christina. The motive: sexual abuse. Maybe he’d been molesting his daughter and things had gone too far. Maybe he didn’t want people to find out, so he’d killed her to cover his tracks. “You’re not a bad guy,” the detectives told him during the interrogation. “We all make mistakes.” No, McNeil insisted, he would never confess “in a million years”; it was Nowlin.

After hours in the interview room, the detectives asked McNeil if he was hungry. He was. He later told me that detectives returned a while later with a scrunched-up McDonald’s brown paper bag. Inside was a kid-sized burger, fries, and a lobster Beanie Baby—identical to Christina’s last meal. Even the toy was the same. Then the police told McNeil that they were interviewing Nowlin, too, simultaneously. He begged detectives to put them together in a room. They agreed.

“Why are you accusing me?” Nowlin challenged him, according to police narratives. “I loved you.”

McNeil shot back, his eyes red, “You killed Christina! You’re a psycho-bitch!”

“No, you murdered Christina!” Nowlin yelled.

The police intervened. Nowlin was released but informed she’d have to take a polygraph test eventually. Some minutes later, she fainted in the police parking lot.

McNeil would spend that night in the county jail on suicide watch after being arrested and charged with the murder of his daughter.

On Christmas Eve 2022, my three-year-old tried to pick up his baby brother and accidentally dropped him. On the way to the hospital, our baby was peaceful. His tiny hand locked around my pinky as he peered out the window at the orange blur of the streetlights in the nighttime drizzle. I felt guilty for a thousand things: for not intervening sooner, for not turning around a second earlier. It wasn’t my older son’s fault; it was mine. Normalcy was so fragile—one minute, things were fine, then they weren’t. Harmony and horror seemed divided by nothing more than an instant. I felt I’d failed to protect my baby in that instant.

Over the hacking coughs and squeak of rubber soles in the ER, the doctor told us he probably had a fractured skull. Results of a CAT scan would tell us if he had internal bleeding. I prepared for a tomorrow in which I loathed myself forever.

But somehow, he was fine. I’d narrowly missed what I supposed was the worst thing that can happen to a person. He would need to be monitored for a while, but my relief was immediate. I burst into tears. I’d never cried like that before.

A day later, crammed into a chair beside my son’s hospital bed, amid the click and drip of hospital machinery, the submarine pulses, I remembered a story I’d heard about a father in Illinois who’d spent the last quarter century in prison for the murder of his three-year-old daughter. He claimed he was innocent.

I’d heard it maybe a month before, but the man’s story came back to me now, as my son slept beside me, still wrapped in a tangle of tubes as I contemplated what nearly happened to him, to me.

If what I’d read was true and Barton McNeil was innocent of killing his daughter, then it occurred to me that I’d been wrong the night before. Losing a child was not the worst thing that could happen to a person: Being unjustly locked up for it was.

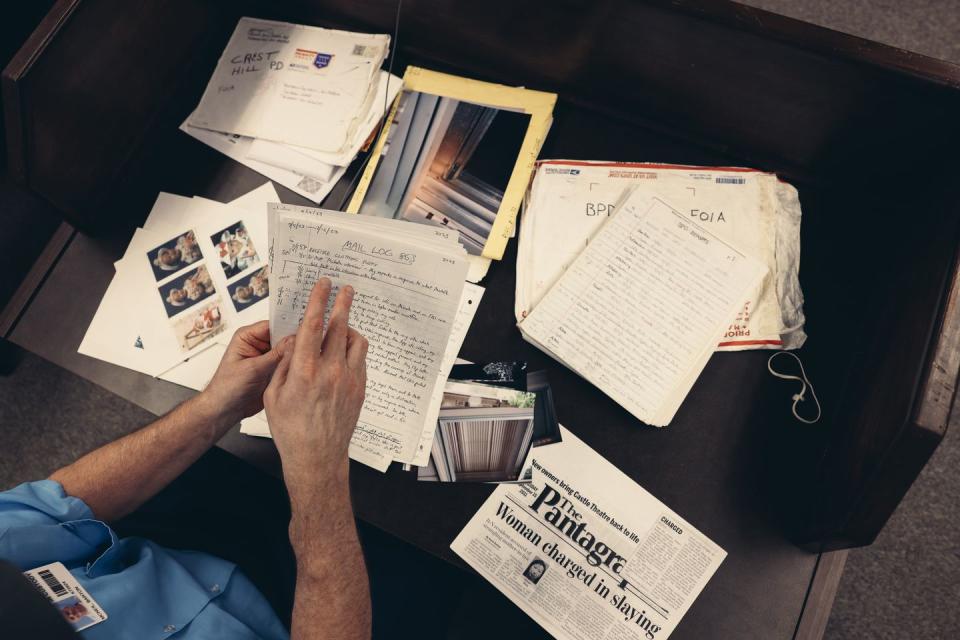

But could it be true? For months, the question wouldn’t leave my mind. I read court documents, scrutinized police reports, and exchanged countless emails with lawyers and criminal experts. Spoke to McNeil on the phone at least once a week. As luck would have it, there would be a hearing in November 2023 to see if his lawyers could convince a judge to order a retrial of McNeil—a chance, decades later, to prove his innocence.

If McNeil didn’t kill Christina, then who did? And if he didn’t, what had those years been like since the moment his old life ended in one horrible instant?

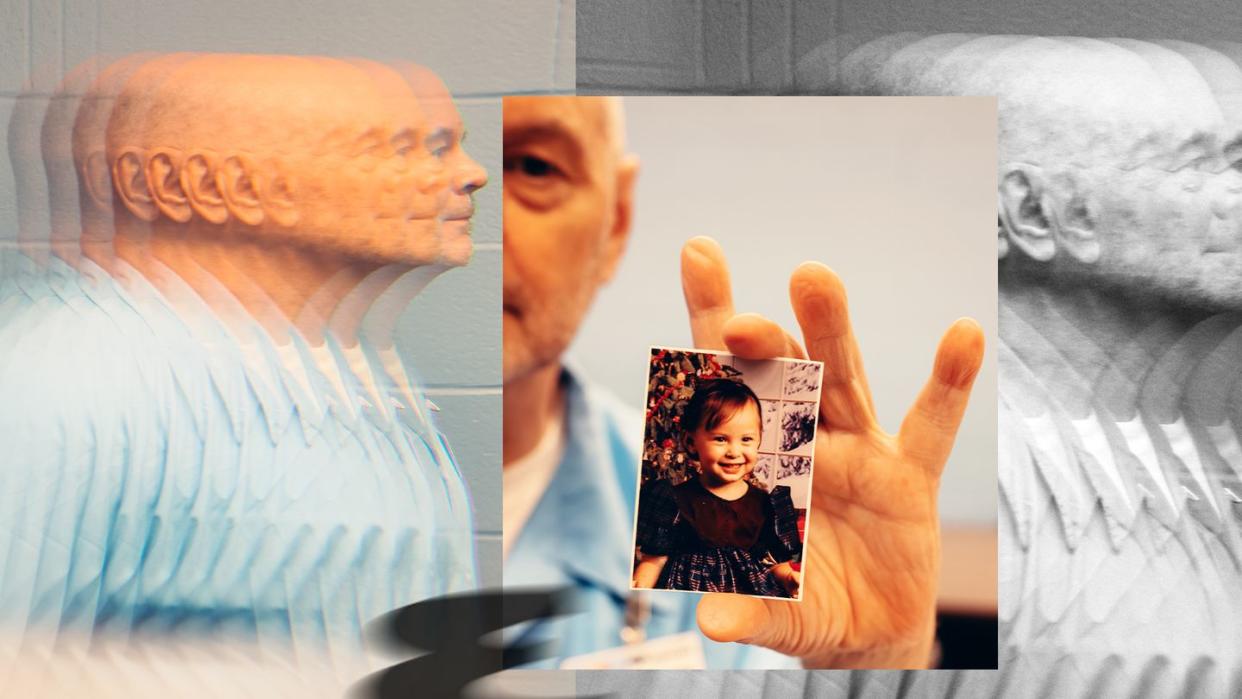

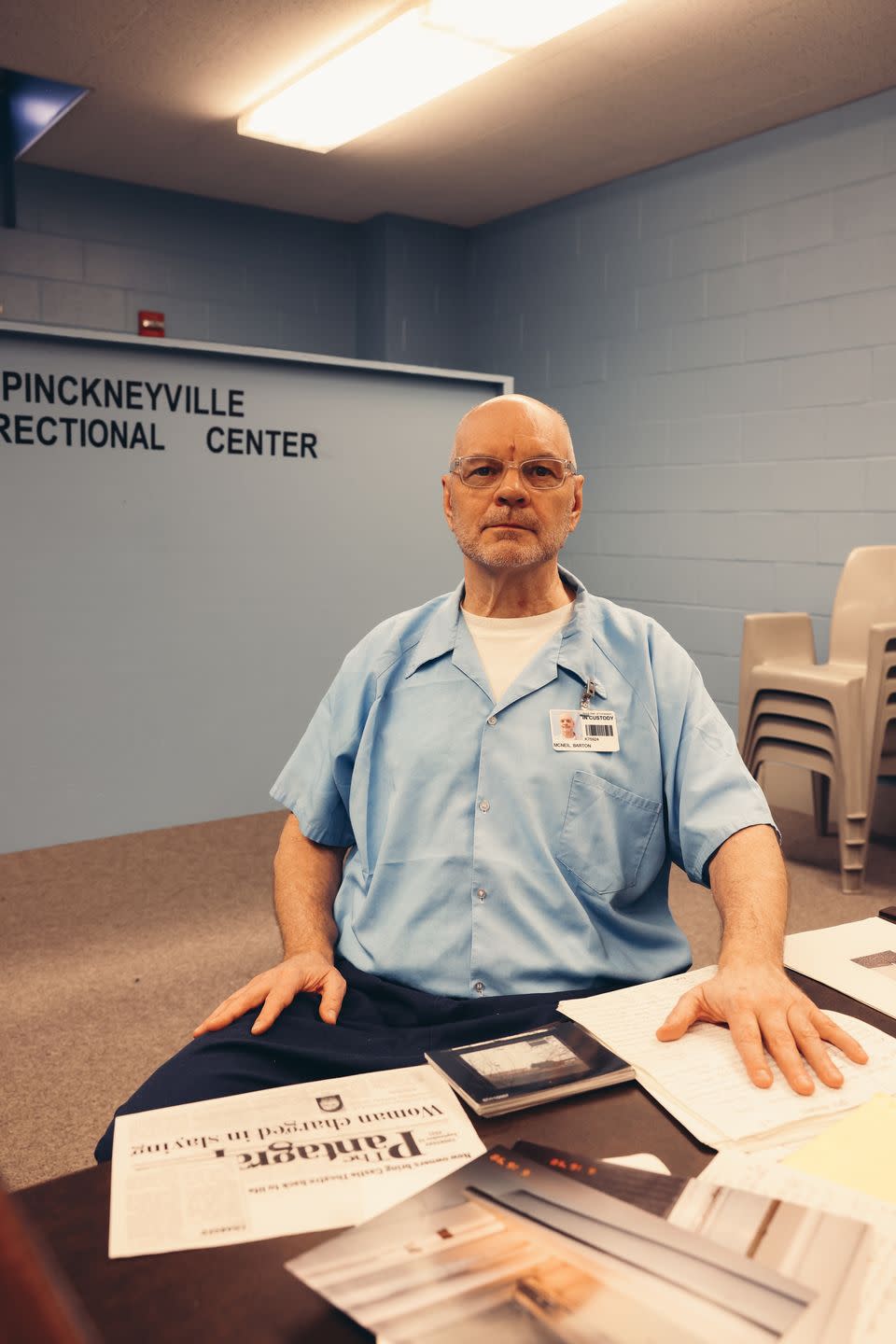

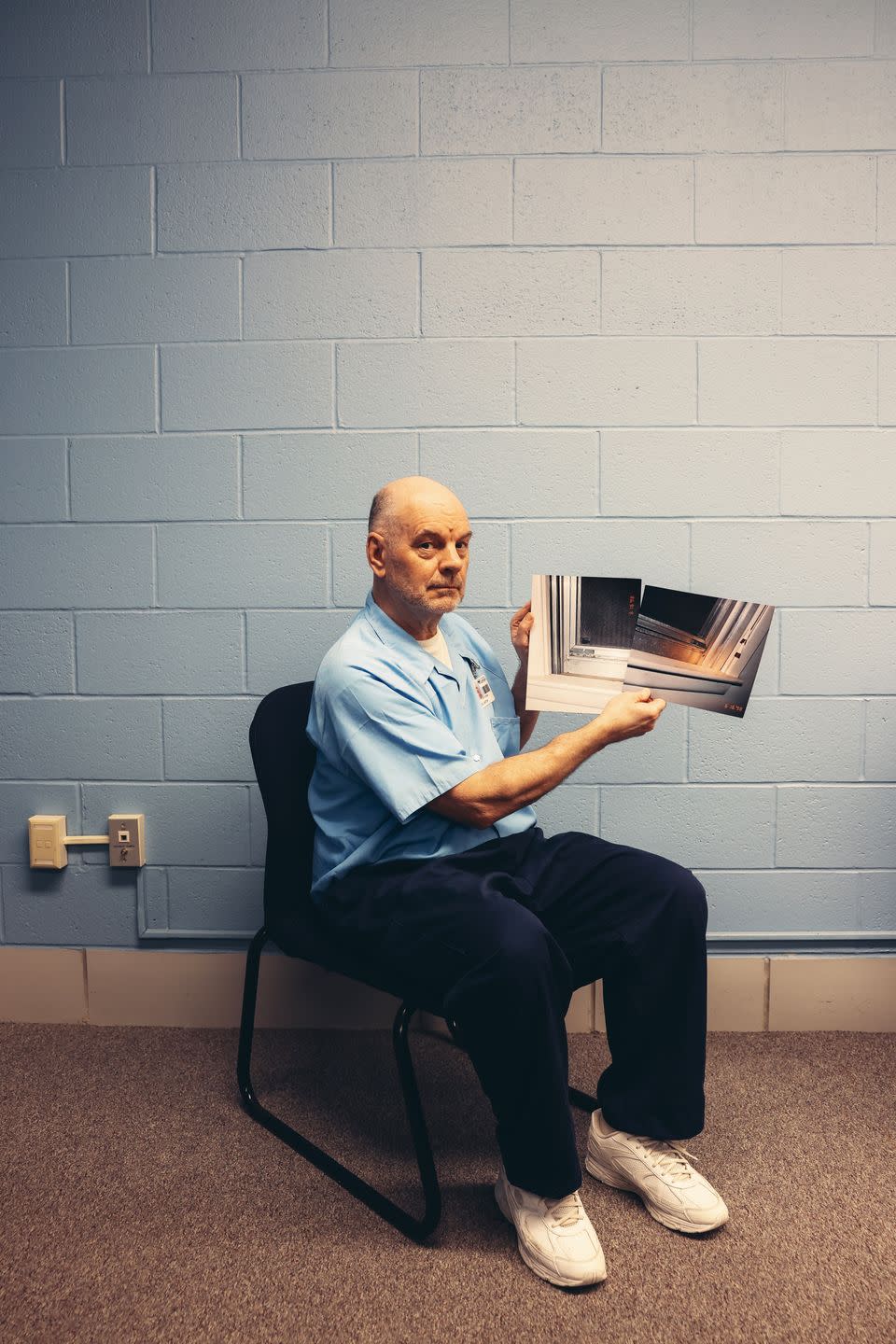

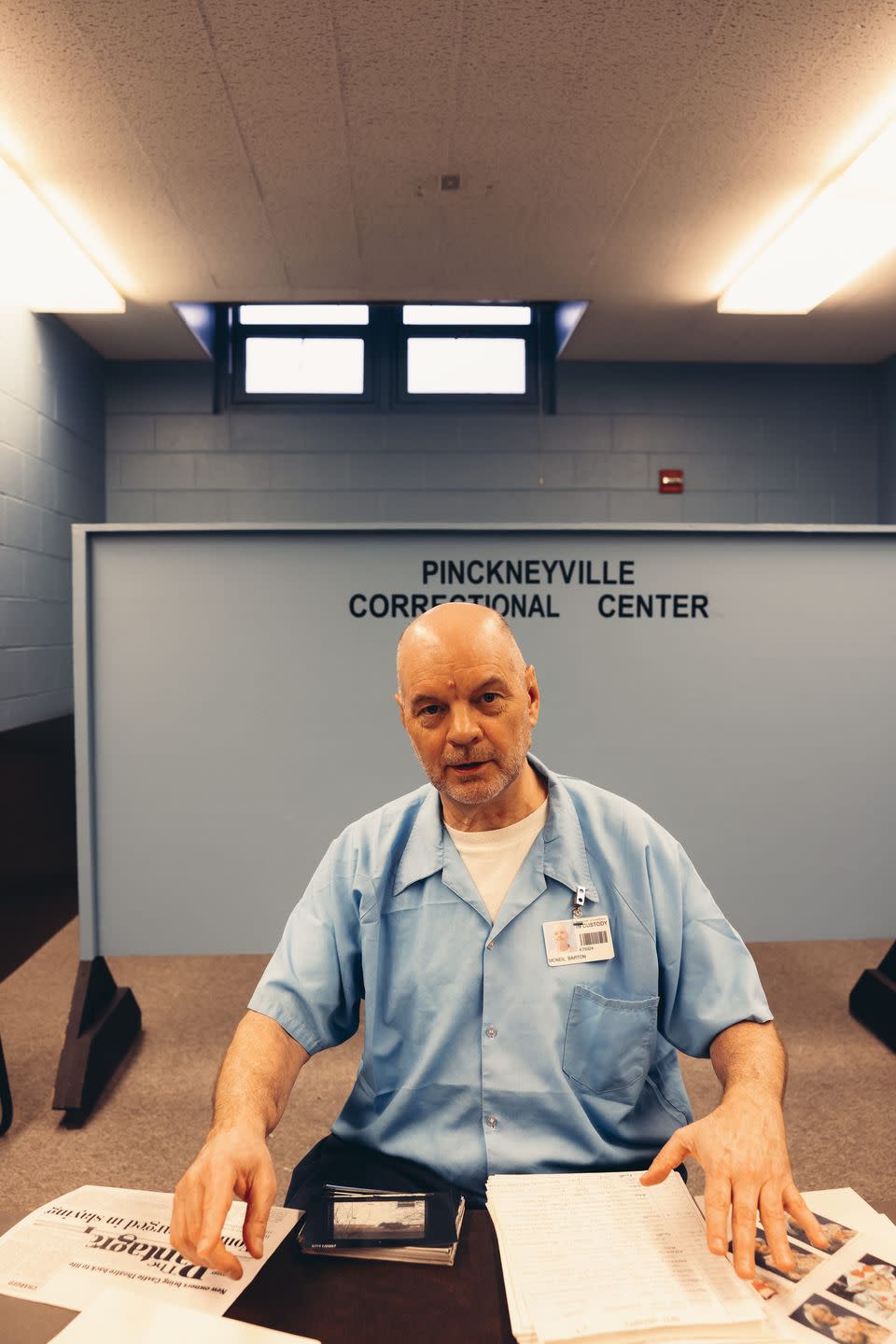

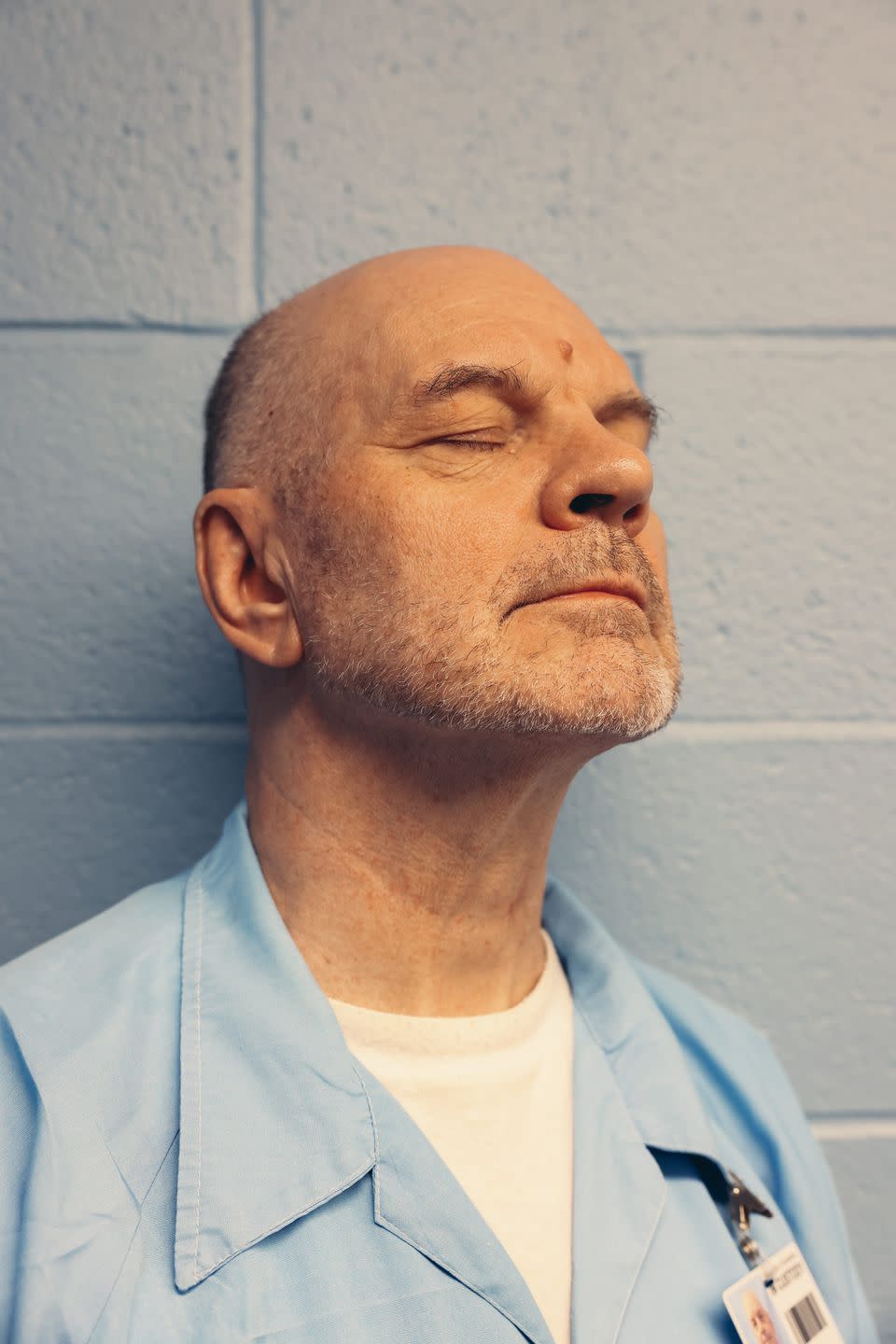

In June 2023, I visited him at the Pinckneyville prison in southern Illinois. I entered a large, austere room, with round tables and fixed steel stools. McNeil’s remaining hair was now gray; he seemed skinnier than in photos, a blue shirt stretched across his bony shoulders. His voice was nasal but steady: “Good to finally meet you in person.”

McNeil told me that after his arrest, of all the people he was desperate to convince he hadn’t done it, none mattered more than Christina’s mother. He frequently wrote to her from county jail, pleading for her forgiveness. “This letter is the most important and saddest letter of my life,” he wrote. “My eyes are rivers of tears as I write this to you. I am begging you, Tita, on the ashes of our beloved Christina and on the grave of my late mother. I never harmed our baby, Tita. I never ever harmed my one and only precious baby. I am on my knees begging you Tita, to believe me.”

On the night of her death, McNeil had custody of Christina as part of his shared parenting arrangement with Tita. After their breakup, she had become more trusting in his ability to care for their daughter, and McNeil, in turn, had taken great pride in raising Christina. She had given McNeil a purpose beyond satisfying his whims—in the main, getting drunk, or chasing women in bars after work. She made him happy to be at home and determined to be better than he was—or, at the very least, better than his parents had been.

His childhood wasn’t horrendous, but it lacked warmth. His parents divorced when he was just six years old, and he and his brother moved from Bloomington to live near family in Wisconsin. Soon after, his mother was discovered dead on the kitchen floor, a bottle of pills nearby.

McNeil and his brother moved back to Bloomington to live with their father, an icy, indifferent man, and his father’s new partner. As a teen, McNeil drank beer and smoked weed. He dropped out of school, believing he could never graduate. He worked a few low-paid jobs at old folks’ homes and local restaurants. In 1979, he was arrested for dealing prescription pills.

There were moments of promise, though. In his late twenties, McNeil aced the GED test. He got a Pell Grant to attend Illinois State, and he almost graduated. There was emotional stability, too.

McNeil had a thing for “Asian gals,” as he once told me. And in the late eighties, after a colleague at Red Lobster introduced them, he started writing to Tita, a Filipina woman who worked as a midwife in Saudi Arabia. She was bright and kind and spoke many languages. It wasn’t long before he proposed to her during a visit to the Philippines. And while some of McNeil’s friends saw the situation as a little mail-order-bride-ish, he was insulted by the insinuation. Tita eventually came to live in Bloomington in May 1993.

They had good times together, but there were fights, too. Tita told the police he could be cruel and indifferent, and one time, she told them, McNeil even “grabbed her by the hair and shook her around.” That fight ended in Tita taking out a restraining order against him. McNeil told me he was deeply ashamed of these actions. (Despite attempts to contact Tita McNeil for this article, I could not reach her.)

McNeil had been a scumbag to Tita; he knew it. In fact, he was having an affair with Nowlin during Tita’s pregnancy with Christina. Although he ended up leaving her for Nowlin, in the spring of 1998, he’d been trying to set things right. But by June 16 of that year, all hope for the future was gone. He’d lost his daughter, and he was losing himself. “And then for Tita to now condemn me, I mean, I just, my whole life was destroyed,” McNeil told me, his voice breaking.

For several weeks after his arrest, McNeil convinced himself the police would eventually realize their mistake. That changed after his indictment, when he began to feel that the system, and even the community, was against him. A journalist for the local paper, The Pantagraph, asked him, “Is it not more likely you did it? Maybe you are mentally ill.... Maybe demons haunt you and control you.”

His family scattered, telling him to stop pointing the finger at Nowlin. But he refused. McNeil wrote letters to friends and journalists, pleading for their intervention. He wrote to the lead detective in the case, Larry Shepherd, whom he begged to investigate Nowlin. “I have always been certain that some of you believe what I have told you,” he wrote in mid-July 1998, with a combination of hope and frustration. “I have learned that the investigation is ongoing and that Misook is still a suspect. For that, I’m very thankful.”

McNeil was right. Detectives were aware of Nowlin’s conviction for domestic violence against him. Police searched her home and seized two vibrators, items McNeil alleged she might have used to assault Christina sexually. But none of Christina’s DNA was found on them. They subjected Nowlin to a polygraph test (an investigatory tool that’s now widely considered to be unreliable). During the test, she denied entering McNeil’s apartment on the night of Christina’s death and denied suffocating her. The examiner noted Nowlin’s difficulty with English and her “erratic and inconsistent responses,” which made it impossible for him to offer an opinion on her answers.

Then, in mid-September 1998, the lead detective on McNeil’s case began an unrelated investigation of Nowlin. Her nine-year-old daughter, Michelle Nowlin, had told her school principal, Aissa Frasier, that Nowlin was abusing her. Frasier sounded the alarm to social services. In pretrial testimony in that case, Frasier said: “[Michelle] had a bruise on her thigh that was several inches long, maybe three inches long or so.... It was apparent that it had been there for a while.”

Frasier told the court that Michelle claimed that her mother had vowed to end her life while pinching her nose and clamping a hand over her mouth. “She needed to behave or the same thing that happened to her sister [Christina] would happen to her,” Frasier said in court.

Years later she remembered, “I said, ‘What do you mean “happened to Christina”?’ And she goes, ‘That’s my sister. She died this summer.’ And that’s the first time I realized. Oh my God.”

Michelle also told Department of Children and Family Services caseworkers that after Christina’s death, Nowlin said she found the bed Christina had died in at a local Salvation Army, where Nowlin was doing community service. Michelle informed DCFS workers and police that her mother had told her she might take it home, saying she wanted to “remember” Christina. While Michelle said she didn’t feel threatened, a DCFS investigator wrote in a report that in her view, the bed was a way of “taunting Michelle with the murder of Christina.” Both Michelle and Nowlin told me that their memories of these events were hazy. Nowlin said that Michelle was a young girl at the time and guessed the story was an attempt at revenge after Nowlin had hit her.

McNeil had access to this DCFS report and the police report about the incident through his lawyer. In the county jail, he was becoming more and more impatient. He knew that forensics revealed an absence of semen on the bedsheets, on Christina’s clothing, and within her body. That surely discredited the state’s theory of sexual molestation, he assumed. The detective found hairs in Christina’s hand, which hinted at a struggle.

It was McNeil’s intention to bring all of this up at trial in his own defense. But in December 1998, the state’s attorney filed a motion seeking to exclude any evidence and arguments that implicated Nowlin in Christina’s death. “In this case, the defendant’s assertions against Misook are founded entirely on speculation and unsupported by the evidence,” the state wrote in its motion.

McNeil’s lawyer countered by presenting numerous witnesses at a March pretrial hearing, known as an “offer of proof” hearing. Their goal was the opposite of the state’s: to persuade the judge to admit all evidence pointing to Nowlin.

Among the witnesses the defense called was the DCFS investigator, who testified that nine-year-old Michelle told her that her mother had beaten her and covered her mouth, threatening, “I will kill you tonight.” (Nowlin denies that she said this.)

The defense also called Misook Nowlin’s former husband Andy Nowlin, who told the court that the night before Christina’s death, he’d received a call from Nowlin. She wanted to “set up” McNeil by planting marijuana in his car. Andy figured she wanted to get him in trouble but didn’t really know why. In her testimony, Nowlin claimed not to remember if she’d called Andy, but phone records showed that she rang him three times that night, the last time at 10:52 p.m.

Nowlin denied going to McNeil’s apartment that night and denied that she’d asked Andy for marijuana. But in the same line of questioning, she seemed to contradict herself. “I asked him maybe—I just joke around with him. I don’t ask him seriously, you know,” she qualified. She claimed that she’d shown up at McNeil’s home the morning after Christina’s death for some computer help, and “also I just kind of miss him.”

In a huge blow to McNeil’s defense, the court ruled that evidence of Nowlin’s potential involvement would be excluded from his trial. The trial date was confirmed for June 1999. McNeil opted for a bench trial, afraid a jury might be too “emotional.”

McNeil wrote Tita again after the judge’s ruling, pleading for help. She hadn’t replied to any of his previous letters. “Defending myself is making me weary,” he wrote. “My own conscience is clean, but I wish others knew the truth, too.”

At trial, the defense called three witnesses, including McNeil. The state called fifteen. The prosecution pointed out that he was home with Christina that night and dismissed the notion of an intruder; the hole in the bedroom window screen could have been there long before. (Two detectives did confirm the presence of more than one hole, and one detective mentioned that the screen seemed slightly off its track and “just fell out” when the police attempted to move it.)

Dr. Hnilica, the forensic pathologist, testified that swelling in Christina’s vaginal area was “in the realm of molestation.” She established a time of death based on digested stomach contents (a technique that even in the late 1990s was known to be imprecise), which indicated to her that the death must have occurred at 10:30 p.m. This seemed to invalidate McNeil’s story about seeing his daughter awake at midnight. It also gave Nowlin an alibi.

When a frustrated McNeil took the stand in his defense, he told the court that the police had “paid absolutely no attention whatsoever to what [he] had to say... since day one of my daughter’s death until this, and pardon me for saying this, it has been a bunch of crap.”

He wanted to point the finger at Nowlin, but a judge had already ruled that he couldn’t. Indeed, the judge found there was “no evidence that someone else entered the home” and, referring to the pathologist’s estimated time of death of between 10:30 and 12:30, “certainly not during the time Christina died.” The judge couldn’t dismiss McNeil’s proximity to his daughter that night, nor the possible motive: that McNeil was trying to cover up sexual molestation. He also pointed to McNeil’s suspicious behavior during police interviews: “The video provides important evidence.... It shows a man conscious that a murder had been committed, knew that he was a suspect, and who had formulated a defense.”

McNeil was found guilty of the murder of a three-year-old girl in a Red Lobster T-shirt and day-of-the-week underwear. He was sentenced to life in prison.

After McNeil’s conviction, the state’s word was the word of God to many. Tita didn’t respond to any of his letters, convinced that he had sexually abused and murdered her daughter. His father and brother showed little interest in continuing their relationships. After the trial, McNeil never heard from his father again. He died in 2017.

Between 2002 and 2011, McNeil’s case languished. His appeals were rejected, and no innocence networks would help him. Only his cousin Grace Schlafer was a beacon of hope during this time. She filed FOIA requests, sent letters to forensic pathologists, and made efforts to locate witnesses. But soon, life interfered when she began caring for her father full-time, and her support waned. Isolated, McNeil started to send letters to random people in the hope of company: “They were addresses from this pen-pal website, but none of them turned out to be real addresses. Every letter was returned to me unopened.” The world seemed to have forgotten about him.

There were many times during those years when McNeil wanted to kill himself. Everything had been taken from him—his daughter’s life and, in many ways, his own. He hadn’t even been able to grieve for Christina; how could anyone do so while fighting for their own innocence? He was locked up the day after her death. He hadn’t even been allowed at her funeral. Guilt gnawed at him. He may not have killed Christina, but he’d let the person who he believed did into his life and into hers. That person, whom he’d fallen in love with because she looked like a “Hollywood star” from a bygone age, had ruined his life.

Reaching Nowlin for this article wasn’t easy. It was months before she replied to my emails. When she eventually did, she was hesitant to talk. She didn’t want her words twisted. As something of a precondition, she wanted to know, “Do you think I killed Christina?” I wrote back that I hoped talking with her would help me answer that.

The weeks dragged on with no answer, until, finally, Nowlin agreed to talk to me over the phone. Although she was worried that I wouldn’t understand her English, she talked quickly.

She told me she was born on the outskirts of Seoul to a middle-class family. Her mother died when she was young, and Nowlin had suffered physical abuse as a child. At nineteen, she’d gotten pregnant by a much older man and unwittingly gave up the child for adoption in a postpartum haze.

A new chapter began when she met Andy Nowlin, an American serviceman. Their relationship swiftly progressed to marriage, prompting her relocation to Illinois. The couple soon had a daughter, Michelle. But life in the States wasn’t an immediate fit. Nowlin sometimes spent money without thinking. “It was all about money,” Andy told me. “If there was money there, life is good. There’s no money there. And then it’s all hell.” She even shoplifted for the thrill of it, for which she was convicted twice, first in 1991 and again in 1996.

While Nowlin admitted she had a temper, others claimed she could be just plain violent. She said she saw this as a part of the culture in which she’d been brought up; it was how her father raised her. Michelle told me, “She was physical for sure. There was a paper-towel holder that was wooden; she would mainly hit me in my thighs and my midsection.”

After her domestic-abuse charge, Nowlin said, she “never touched [Michelle] again.”

On the night of Christina’s death, she told me, she was with her friends. She said that yes, she could be jealous, and yes, she had a temper, but that didn’t make her Christina’s killer. She did not crawl through the window that night: “I couldn’t get past that myself, no way.... Someone would have to have pulled me up.”

She said she did not suffocate Christina, whom she called her “daughter,” despite having no biological or legal relation to her: “ I never do that to her.... She’s too precious to me.” When I asked what she thought of McNeil’s belief that she killed Christina, she replied: “One time, I loved him very much. So I understand what he’s doing.... If that’s me in his situation, I’d do the same thing, probably.”

When I contacted Nowlin, it was through the Illinois Department of Corrections’ email system. She’s in prison now—but not for anything having to do with Christina McNeil.

In September 2011, seventy-year-old Linda Tyda, a respected Chinese interpreter, went missing after leaving her home for a job in Bloomington. A week later, a Chinese-speaking restaurant hostess approached the police, claiming that Nowlin—then married to Tyda’s son—paid her twenty dollars to act as a client and arrange a meeting with Linda Tyda. Tyda agreed to meet this “client” in a grocery store parking lot.

Surveillance footage revealed that instead of the hostess, Nowlin met Tyda in the parking lot. They argued, and Nowlin grabbed Tyda’s arm and purse. After the altercation, both women left in their cars. Tyda followed Nowlin to her sewing shop in Bloomington and was never seen again.

The authorities questioned Nowlin based on the hostess’s statement and the surveillance footage. A search of Nowlin’s shop made a significant discovery: Tyda’s cut-up ID card, credit cards, and last-worn clothes in a dumpster behind the shop. Nowlin soon confessed to killing Tyda.

When a friend sent McNeil a newspaper clipping and Nowlin’s mug shot, McNeil convinced himself there were similarities between the deaths of Linda Tyda and his daughter. There was the method: Both Tyda and Christina had died from asphyxiation, although Tyda had been strangled and Christina was smothered. (In a jailhouse letter that Nowlin wrote to Michelle after the murder, she admitted, “I started to lose control of myself too and pushed Linda away. After that, we came into a situation where we were strangling each other. I was really out of my mind.”)

Then there were the victims: As McNeil saw it, Nowlin had targeted the loved ones of people she wanted revenge against. She had lured Tyda to Bloomington under false pretenses. And wasn’t she planning to exact revenge on McNeil for refusing to testify in her favor at the domestic-battery sentencing when she called up her ex and asked for help in planting marijuana on him?

Now all those who had doubted him would surely listen, McNeil felt. If only he could reach them. After weeks of trying, he managed to get through to the local radio station from prison. When the host took his call, McNeil was gasping; he always seemed at the end of his breath—he had only minutes to convince listeners: “The premeditation she allegedly used in the murder of Mrs. Tyda was every bit as elaborate as the premeditation she used to murder my daughter,” he panted over the airwaves.

Chris Ross and his cousin Barton McNeil had met a couple of times at family gatherings but had never been close. He knew about the sad story of McNeil’s daughter from his mom and felt for him, but he hadn’t thought much about it—and certainly had no desire to get involved.

But then he heard his cousin on the radio.

In December 2011, Ross wrote his first letter to McNeil: “Immediately after hearing your radio interview, I became your #1 Fan. Seriously, you were wronged and I plan to do everything in my power to get you free through legal means.”

Ross started to call his cousin each day. He’d tuck the kids in at night and stay up until 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. to study thousands of pages of discovery, hoping to find something, anything, that could help him. The lawyers Ross consulted all seemed to recommend the same thing: a private investigator, specifically Kevin McClain.

McClain had been a PI for almost twenty years by that point and had worked on many capital cases. When he spoke to Ross, he was “mesmerized” by McNeil’s story. He couldn’t believe that McNeil, not the police, had demanded that the case be investigated as a murder: “I’d never seen it before... the man who’d started the homicide investigation was the one who eventually ended up accused of it,” he told me over the phone.

McClain had links to the Illinois Innocence Project, which worked pro bono on wrongful convictions. He told Ross it might be interested in McNeil’s case. Ross sent McClain a detailed PowerPoint presentation listing the key events and inconsistencies. The investigator would put in a good word.

It worked. On what would have been Christina’s seventeenth birthday, Ross got the news that the Innocence Project had decided to represent McNeil. “There was just no evidence against Bart,” John Hanlon, the former head of the organization and one of McNeil’s current attorneys, told me.

More information emerged. In 2012, a former neighbor of Nowlin’s reported seeing her rummaging around in a shared hallway closet at their apartment complex around 4:00 a.m. on the night Christina died, when Nowlin had told the court and police that she had been asleep.

McClain’s investigators also obtained two signed affidavits, one from Michelle Nowlin and one from Dawn Nowlin, Michelle’s stepmother, stating the same thing: Don Wang, the man Misook married after McNeil’s conviction, then later divorced, claimed that she confessed to him that she’d murdered Christina. Meanwhile, in 2013, Misook Nowlin was convicted and sentenced for the murder of Linda Tyda. On McNeil’s behalf, in November 2013, the Innocence Project filed a motion for additional DNA testing, arguing that only limited testing had been conducted in 1998. When the results came back, Nowlin’s DNA was found on six areas of Christina’s flower-patterned sheets. (Nowlin told me that of course her DNA was on Christina’s sheets: She had slept on that bed many times.)

In 2018, more lawyers, these from the Exoneration Project, another nonprofit organization specializing in overturning wrongful convictions, joined the team. “There was a lot of junk science in [McNeil’s] case,” Karl Leonard, one of McNeil’s attorneys, told me. “It was a case we knew we could win.”

Momentum was building. In 2017, a defense expert, Dr. Andrew Baker, the chief medical examiner of Hennepin County, Minnesota, read the autopsy report and studied the accompanying photos and biopsy slides. He argued that there was nothing in the original pathologist’s reports to suggest Christina “was smothered or that the manner of death was homicide.” He also concluded that significant portions of the 1998 examinations of Christina’s body were performed after a funeral director had prepared her remains, a deviation from accepted forensic procedure. His findings led him to a stunning conclusion: He believed that Christina’s death was due to unexplained causes.

A second defense expert, Dr. Nancy Harper, director of the Center for Safe and Healthy Children at the University of Minnesota, also disagreed with the original pathologist. In 2019, she submitted a report in which she claimed that the area of Christina’s anus and vagina, as documented in the 1998 autopsy, was “normal and without acute trauma or residua of injury.” Christina had not been sexually abused, she concluded.

I felt relieved when I read these opinions—not so much for McNeil as for Christina. Suddenly it seemed possible that the little girl hadn’t been murdered or abused, that perhaps she’d died without suffering.

McNeil didn’t see it that way. “The natural-causes scenario leaves Misook completely off the hook,” he said, his voice rising. It was the logic of it that bothered him: “You know, on the one hand, I’m innocent because Misook murdered my daughter, but on the other hand, Misook is innocent because it wasn’t a murder and it was a natural cause of death. I do not sign off on that.” For McNeil, there was no relief, no version of this story in which Nowlin was not the culprit.

A version of this article appeared in the March 2024 issue of Esquire

subscribe

It struck me that proving Nowlin’s guilt (as well as getting the justice he wanted for Christina) was the reason he kept fighting. She was the cause, the avatar representing the otherwise inexplicable arc of his life. Someone had to be to blame for his misfortune; otherwise it was all too brutally random: His daughter died in his home, in her sleep, and he was convicted of her murder. It was too cruel to contemplate.

McNeil’s legal team filed a post-conviction appeal in 2021; it included all of the newly discovered evidence not available back in 1999. They hoped to force an evidentiary hearing—to present this new evidence in court and prove to a judge that if it had been available in 1999, McNeil wouldn’t have been convicted. If the judge agreed, McNeil would be granted a new trial.

But the state’s attorney’s office was far from receptive. (The office of the McLean County state's attorney declined to comment for this story, since the matter is still before the court.) It brushed off the presence of Nowlin’s DNA on Christina’s sheets, arguing that her close relationship with McNeil made finding her DNA at the scene inevitable. McNeil produced a bank statement, evidence of a laundry visit the day before Christina’s death. (Forensic experts I consulted confirmed that laundering the sheets would obliterate any lingering DNA.) The state countered that, too: The laundry receipt wasn’t itemized, wasn’t proof of anything.

The state challenged the findings of the defense’s pathologists, arguing that since the research papers they cited were published before the crime took place, they weren’t “new.” The state’s attorney also refuted the alleged similarities between Tyda’s murder and Christina’s.

In 2022, following an examination of the evidence and the state’s attorney’s rebuttal, the judge ruled primarily in favor of the state. His decision rejected a significant portion of the defense’s evidence: the DNA, Nowlin’s conviction for Tyda’s murder, the testimony about Nowlin and the storage space on the night of the death, and the new autopsy reviews. A public evidentiary hearing was scheduled for two days before Thanksgiving 2023. The only evidence the judge would allow to be considered that day was the affidavits related to Nowlin’s confession.

Three days before the hearing, McNeil seemed exhausted. He was on edge about seeing Nowlin again. It had been twenty-four years since she testified at his pretrial hearing, in early 1999. In the intervening years, she’d gotten remarried and divorced. (Although I’ve referred to her by her previous surname, her last name is now Wang.) But mostly he seemed exhausted by hope. “Back when the case was dead, there is a relief with that,” he said. He felt he owed his supporters something and owed it to Christina to show the world what kind of person Nowlin was. But in truth, he just wanted it all to be over.

On November 21, a clutch of twenty or so of McNeil’s supporters huddled in the lobby of the McLean County courthouse, chatting nervously. Chris Ross darted around handing out free bart badges and corralling the group for photos. A few of McNeil’s childhood friends had gathered, along with journalists, and a man who was suing McLean County for wrongful conviction. As 9:00 a.m. approached, the onlookers filed into Courtroom 5A, where the atmosphere resembled that of a hospital—sterile and tense.

Michelle Nowlin was the first to take the stand. She called “Bart” McNeil a “father figure” and described the celebration-of-life ceremony held for Linda Tyda, where Don Wang told her something that caught her off guard. “Randomly, just out of the blue, he said, ‘You know what your mom told me one time?’ And I just sat there and stared at him and said, ‘No, what is that?’ And he said that she had killed Christina,” Michelle testified.

Michelle’s stepmother, Dawn Nowlin, second on the stand, corroborated Michelle’s account of the conversation. “He said that he and Misook were in a big fight, and she confessed to killing Christina,” she told the court.

The defense called Misook Nowlin.

Shackled and wearing a white polo shirt, she shuffled into the courtroom. Strangely, she winked at the crowd. One of McNeil’s attorneys, Karl Leonard, asked: “Did you kill Christina McNeil?” Nowlin invoked the Fifth Amendment. So Leonard instead referred to her police interview in 1998, in which Nowlin said she was still in love with McNeil. Nowlin again pleaded the Fifth.

Leonard kept going: “You told Detective Wycoff that a few days before Christina’s death, you had gone over to Bart’s apartment and discovered some condoms in the bathroom, so you were suspicious he had another woman. Right?”

“I plead to my Fifth,” Nowlin replied.

“So you searched the trash can to see if you could find more condoms, but instead you found some printed emails that he had exchanged with an Internet girlfriend, right?”

The state’s attorney objected.

“Relevance, your honor,” he murmured.

“What’s the relevance, counsel?”

It went to motive, Leonard said. Sustained.

Suddenly, Nowlin seemed to burst with frustration, declaring in answer to no question at all: “I never kill Christina McNeil!”

Leonard, taken aback, asked her if she was indeed pleading the Fifth. Yes, she said, she was, and answered no more questions.

The rest happened quickly and without drama. The state called former detective Steve Fanelli, who disputed the testimony of Michelle and Dawn Nowlin about Don Wang’s story. The defense and the state rested their cases. The judge would issue a written ruling soon.

McNeil was then ushered out of the courtroom, sheepishly waving to his friends in the public gallery as he disappeared behind the door.

After the hearing, I stopped by 1106 North Evans Street, where Christina died twenty-six years earlier.

McNeil’s home was gone, demolished to make way for new apartments. So I looked at the photographs of the old one-story building on my phone—at its white facade, the yard with Christina’s bicycle out front, the overgrown shrubbery, and the porch light.

For all the uncertainty that bedevils this story, there is one thing everyone knows to be true: The owner of the bicycle is dead. Normalcy can turn to horror at any terrible moment. In McNeil’s case, he’s spent most of his adult life trying to prove to anyone who will listen that his terrible moment has been interpreted all wrong.

When I talked to him by phone later that day, he said he felt the state had done its damage. In February, 2023 the judge ruled that McNeil would not be getting a new trial. He would appeal the verdict to a higher court, but an appeal in state appellate or federal court was a long way off, if his case ever reached them. The hearing was a dud, he said. In his view, the court and Nowlin had, together, ruined his life. “I’m sixty-five. The average life expectancy for males is seventy-two. I’m likely to die in prison,” McNeil had told me once.

Now all McNeil had were the people who had come to see him in court two days before Thanksgiving. The people who wore the buttons. All his hard work, all his letters, his thousands of pages of notes, his hours on the phone—they had worked for that at least. There were some people out there who believed he hadn’t killed Christina. That was enough for now, he said—and it might have to be enough for him forever.

You Might Also Like