The Really High Highs and Embarrassing Lows of Oliver Stone’s First Oscar Season

The backstory to the Oscars competition is the misery that hunt entails for everyone. Back then it was a “big deal,” but nothing compared to what it became in the 1990s, when Harvey Weinstein and Miramax took the art of promotion one step further. There was always the unfounded rumor of “buying votes,” as there’s a lead-up chain of events beginning with the Golden Globe awards in early January. The Globes are given out by a coterie of foreign journalists in Hollywood. A rather meaningless group of publicity-creating writers without real readership in their home countries, they had nonetheless accumulated “standing,” which all producers chased after as a signifier of social popularity, like a high school election. There were also the film critics’ awards in New York and Los Angeles. They had their own signifiers among themselves, mainly self-contained, I believe, until “Harvey,” as Weinstein was always known, penetrated that circle. They often skewed to the less commercial films, or to put it another way, films not necessarily waiting to be seen by a real audience. Midnight was way too vulgar and successful for their consideration.

The January night at the Golden Globes took a peculiar turn for me. There’d been several parties in the days leading up to the ceremony where I finally met Brad Davis, the hot new star of Midnight Express; he seemed a volatile, angry young man who grew in the part. He was close to the real Billy Hayes, and the three of us ended up sharing alcohol, quaaludes, and some cocaine, which was making its reappearance in Hollywood as a party drug back in vogue, I believe, for the first time since the 1920s. There were always private users, but this was a popular, just-below-the-surface public thing with younger actors beginning to enjoy it. It was sexy, innocuous enough, and fun. It sparked great energy and laughs, and was nothing more to me—at first. A terrific burst of “friendly fire,” yes, but I already had great energy. So I’d do it here and there, including at the Globes, which was known as a fun and unexamined party, not at all like the Oscars.

So as the speeches and the television awards dragged on for three hours before the big film awards in the last hour, the three of us, Billy, Brad, and myself, did cocaine in the men’s toilets of the Beverly Hilton ballroom; several other parties of people were also stepping in and out of stalls that night. And at our table, front-center, first row—thank God this was in the pre–live TV broadcast days—we were laughing among ourselves, having a great time as Midnight Express director Alan Parker glared at us. He was not a happy man, and I suppose the prospect of waiting around for Michael Cimino to win the director award for The Deer Hunter further darkened his view of the world.

So it was after a few hits of coke, a quaalude or two, several glasses of wine over three hours, that finally my name was called for screenwriting adaptation. Not that I was surprised, because many people had told me I’d win. I felt like a racehorse they were betting on, and I’d come in on a two-to-one bet. The applause was tremendous in my ears, the ballroom floating in the pure joy of this moment. My rebel side had been restive the whole night, or perhaps since I’d seen Parker’s glum face earlier, and it reminded me of all the indignities he’d piled on me. Who knows? The devil was in me that night. And here we were, at a ceremony with all the people who’d rejected Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July and lavished applause on a bunch of television cop shows up for awards. I’d seen the shows, disliked most of them, representing the triumph of Nixon’s “law and order” world, jailing the underclass, the black, the Spanish as “bad guy” drug dealers, outsiders. All these actors and producers being lauded for fawning over cops. I hated the whole self-congratulatory air of the night.

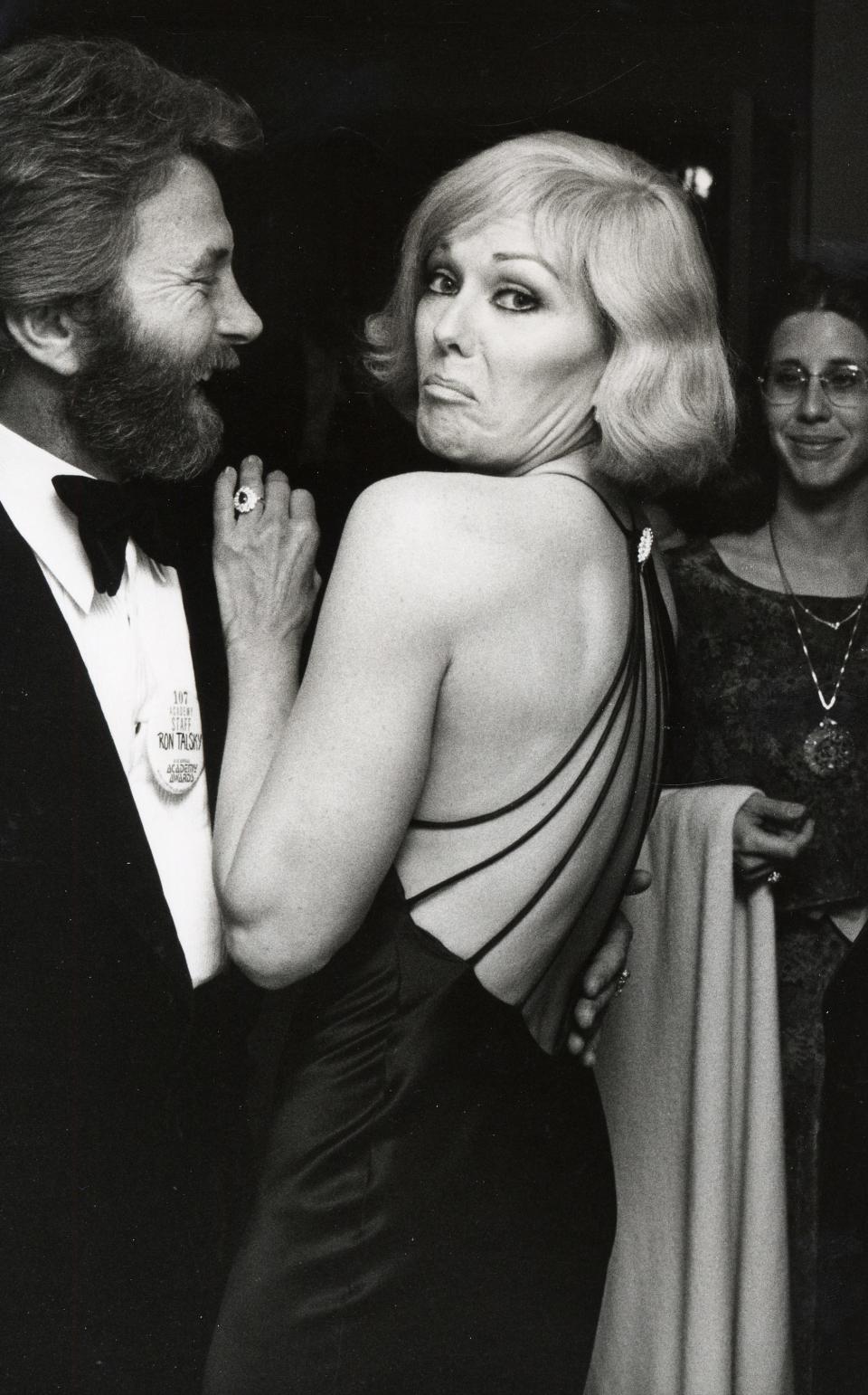

51st Annual Academy Awards

There was something else growing inside me, but I couldn’t articulate it. I’d seen it in Vietnam. That the US was always quite ready to lecture others on how to behave, be it about drugs or human rights, while ignoring our own giant appetite for drugs at home. I’d always despised bullies, at school, in war, and now I was finding them here, in my dream city—Hollywood. But far more subtly. The biggest bullies quietly control the airwaves, the content, the attitude, and you do not veer too far from what is “thinkable.” So when I got to center stage to accept my Golden Globe and have my moment, I started to explain to the audience what I was really thinking, which wasn’t necessary, but certainly Brad’s and Billy’s faces were egging me on. I was trying to say something like this, which is far more articulate, probably, than what I said.

“Our film’s not just about Turkey . . . but our society. You know, we arrest people for drugs, and we throw them in jail . . . and we make heroes of the people who do that . . . and . . .” It was going on. Seconds. It wasn’t clear. My tongue was dry and heavy in my mouth, and I was trying too hard to explain my concept of how we condemned people to jail without recognizing what we were doing to ourselves as a nation. But it got so lost because I hadn’t written it in advance, and I was more zonked than I thought. I was losing them. I now heard a dead silence in the room . . . then the hissing started, and it grew.

The next thing I recognized was the exit cue music as co-hosts Chevy Chase and Richard Harris, both formidable partiers in their own right, were coming from stage left and right to get me, that is to “accompany” me offstage as quickly and politely as possible—as the hisses and boos rang out in an ascending chorus. My message was clearly lost. I was embarrassed when I walked back to our film’s table, which was, as I said, front and center. I was not uncomfortable with what I was trying to convey, and perhaps some had understood me, but they were silent as the awards pounded on to their conclusion. Parker, flushed with red wine, glared at me, while Puttnam and Guber avoided my eyes. Brad and Billy just smiled neutrally and moved on to the next round of applause.

Cimino indeed won Best Director for The Deer Hunter. Then Heaven Can Wait received Best Picture–Comedy, which brought Warren Beatty to the stage in his peak splendor as producer, co-director, co-writer, and actor. And then, surprisingly, Midnight Express upset Deer Hunter for Best Picture–Drama. That shocked us, and Peter Guber and David and the two Alans, Parker and Marshall, took their turn on stage. And then the music wound up the exit cue, and after three long hours, the tuxedoed crowd stood up to leave.

Parker wasted little time coming right up to me, vindicated. “You just blew it, Oliver. That was your Oscar. Think you’ll ever get one now? The worst thing is—you hurt the film.” He was so palpably angry, wanting to punish me; the actor Tom Courtenay could have played him perfectly as the class-hating communist commissar in Doctor Zhivago, or the overbearing British POW in King Rat—same voice, characteristics, and look, with all the meanness of a British school and class system that had eaten at his soul. Puttnam chimed in something like “this is really going to hurt us,” and even Peter Guber, to whom I felt more loyalty than to the others, stopped and, though delighted by the picture’s win, commiserated without personalizing it: “I wish you hadn’t done that. Congratulations anyway.”

The room emptied, no one seeking me out. I went home sad and still ashamed. The Oscars were still two and a half months away, but I had blown it. For our picture, perhaps. I’d certainly destroyed my own chances, but that was okay. I hadn’t gone up there, as Parker thought, to fish for an Oscar. I wanted to share my feelings; what a mistake that was. Feelings. So dangerous when you express them.

My agent made light of it the next day. There was actually a kinescope made of that night, in the years before the show was telecast widely around the world, which I saw twenty-five years later on YouTube, although it’s since been removed. It made me laugh. What a fool I was. Not for what I said but for saying it so badly. But Hollywood at that time was actually far less hysterical and more tolerant than it’s become. The incident was simply noted in Variety and the Hollywood Reporter. I was talked about—“Stone must’ve been high!”—but it was funny, part of the general loosening mood with a younger generation coming on in the later 1970s—the “Young Turks,” as Jane Fonda labeled us. And with no TV broadcast, there were, after all, only about a thousand people in that ballroom, so it never grew into a shaming event, as it would today.

In the week of the Oscars in April 1979, Barry Diller, the freezing-cold head of Paramount, gave a glittering party. I was still nervous, unsure of myself, when Diane Keaton, who was another one of the top female stars at that time, warmly welcomed me, so unassuming and kind. And then of course there was her then partner, the man who knew the power of appearances, indeed was the ringmaster of all of them. Remarkably handsome, six foot two with those sparkling eyes, Warren Beatty knew he had the gaze of the whole room and could play that for all the genuine, adorably fake shyness he layered into his performance. At that time his bouffant hair was out of Jon Peters’s Shampoo—today it’d make you laugh, but then it was stunning—as he was heading for the Academy Awards for his film Heaven Can Wait. The stars were aligned, and he was already setting Barry Diller up to make his great historical epic Reds, which would almost break Paramount.

A cool, casual hello came out of him, shared with a possible competitor in Midnight Express, and then “Jack,” his buddy, was in my line of sight . . . just ineffably “Jack,” the guy next door. Everyone knew Jack from New Jersey, or thought they did. But in all the times I’d meet and talk to him, and be fascinated by him, never did I think I knew him—or, for that matter, comprehend the meaning of his beat, Jack Kerouac dialogue. Literally. As close as I’d pay attention, I never understood his long, loopy spiels. And although I’d see people listen and laugh, I’m sure most of them didn’t understand what he was talking about either. That’s the power of Jack Nicholson’s mystique.

When the Academy Awards finally arrived on that Sunday night in April, it was a new peak. I was on Mount Olympus, nervous because everyone, despite my Golden Globes fiasco, told me I’d win—hot, sweaty in my tux, slipping in and out of my chair to check my appearance in the downstairs men’s lounge as the ceremony dragged on into its third hour. I was in my thirty-third year and self-conscious. Christ had supposedly died at this age, thus creating in my mind a dividing line beyond which you aged in mortal fashion.

JOHN WAYNE

It was glamorous from beginning to end, the afternoon pickup at my apartment building by the limousine, the drive downtown, the enormous outdoor red carpet, television interviews, cheering fans, the music roll, the beginning of the Fifty-first Academy Awards! It felt like an intersection of time that night, a changing of the guard. It was a fantasy to see Cary Grant, Laurence Olivier, and John Wayne all at once. Grant, as impeccable in real life as he was on the screen, smiled warmly to me, as if he knew me. And the long-lashed Olivier received an Honorary Lifetime Oscar and, trying to outdo Shakespeare, for once undid himself, giving a flowery, over-the-top, poorly written imitation of Shakespeare. But who cares—he was Laurence Olivier. And then at the end, to present Best Picture, came his opposite—John Wayne, striding alone onto center stage. He was still a big man—six foot four. Dying from cancer, wearing a bad wig, his lungs wheezing with difficulty, he remained a monument of a man; everyone in the room knew it. And by this time, any resistance to his woeful politics was gone. Big John mispronounced most every name and title of the Best Picture nominees. He particularly mashed the name “Cimino” into something that sounded like “Simoncitto,” some immigrant off the boat from Sicily, and then gave the Oscar to the dark Deer Hunter to thunderous applause. It was the chosen one that night, and I was oddly torn. The moment was beautiful, the vision complete; and for me, I guess the Hollywood version of Vietnam—with Jane Fonda and Jon Voight winning the best acting awards for Coming Home, and Apocalypse Now coming out the following year—was now complete. Clearly, neither Platoon nor Born on the Fourth would ever be made, nor did it seem necessary to make them any longer, and that was okay with me. Vietnam was buried—I was at peace with it. It was a glamorous ending to this chapter of my life.

My turn came up earlier. Lauren Bacall, accompanied by Jon Voight, regally walked on to bestow the awards for screenwriting, both adapted and original. She put me back into the Bogart-Huston era, still looking like a lynx with those slits for eyes and that 1940s smoker’s voice. My nerves couldn’t help but take a quantum leap upwards. God help me now. Remember, this audience doesn’t want a lecture on the War on Drugs; anyway, most didn’t agree with me, or they wanted a crackdown on drugs, or they just didn’t want to think about it. On the contrary, the US was clearly drifting toward an expanded prison system, and the fight against crime and terrorism was a popular theme. So be cool, man, say what you gotta say quickly and get off. This was on TV now, going out to hundreds of millions across the globe. Don’t fuck this up, Oliver. Midnight had won only one Oscar so far—for Giorgio Moroder’s tense, driving score. Neil Simon, sitting close by, the most financially successful dramatist of his time, was my competition for adaptation of his own play, California Suite; sitting separately were Elaine May and Warren Beatty for their rewrite of the original Heaven Can Wait.

“And the winner is”—that grand cliché of a pause as Bacall opens the envelope—“OLIVER STONE!” Wow. Cheers breaking all around. I knew this moment was special. I memorized it. I planted it in my heart—like a tree that would grow. I started walking toward the stage. Nothing fancy. Just walk up there, don’t stumble on these stairs.

My speech this time was considerably better delivered than at the Globes, but the meaning again was botched, as I naïvely wished for “some consideration for all the men and women all over the world who are in prison tonight.” Considering that this generality includes some genuine psychopaths and cold-blooded killers was beside the point, because who really listens or cares? I was just another writer up there making a case, my hair tumbling messily down to my shoulders, and presenting a slightly stoned, out-of-it expression. But I was young enough to strike a chord and briefly be remembered in a profession in which, I would discover, writers are profoundly interchangeable. I thanked my colleagues and got off. Lauren and Jon stayed on to give the screenwriting prize for originals to Waldo Salt, Nancy Dowd, and Robert Jones for Coming Home.

Backstage was brutal, nothing like I expected. Lauren abandoned me, stars were moving left and right to get ready for the next number. Cary Grant smiled at me again. There was Audrey Hepburn! Then Gregory Peck! Then Jimmy Stewart was congratulating me, the warmest of men. Then fifty photographers were popping flashbulbs in my face in one room, and in the next, another fifty reporters were throwing tough questions at me like grenades. I did my best and, soaked like a sponge with sweat, gratefully returned to my seat for the finale with John Wayne.

I went on to the Academy Ball and other parties, giddy, drinking, ending up quite high and drunk at a Hollywood Hills mansion where so many people congratulated me it became a blur. Alan Parker’s face loomed up somewhere that night. A begrudging congratulations. Nothing more needed to be said between us—for years. I remember chatting with a cerebral Richard Dreyfuss, who’d won the acting award the year before for The Goodbye Girl, then being embraced by Sammy Davis Jr., who was hugging me and “spreading the love, baby!”

51st Annual Academy Awards

And then, out of the smoke and music, near three in the morning, emerged a goddess, now older but still desirable, her voice strained and hoarse enough to seduce any Odysseus shipwrecked on her island. Kim Novak was Circe, able to turn men into swine, but alas, she preferred her dogs and horses on her Northern California ranch, where she lived in reclusive splendor. As I talked with her quietly on the couch, she seemed to me a woman who, never satisfied with men, had found her lonely island. I yearned for her without saying it, and felt her isolation. She was amused by men, accustomed to being desired, but could never be mortal. She preferred her dream.

Three short years ago, I’d been in the gutter. Now I was on a mountaintop I’d never thought possible. And in three more years, I’d be back in the gutter.

Adapted from Chasing the Light: Writing, Directing, and Surviving Platoon, Midnight Express, Scarface, Salvador and the Movie Game by Oliver Stone, to be published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on July 21, 2020.

Originally Appeared on GQ