I Recently Uncovered Some Memos From My Days as a Hustler Editor. Holy Hell.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For a publication priding itself on an in-your-face flouting of social norms, behind the scenes it seemed like Hustler magazine in the early 1980s was run more like a neurotic military cabal. With publisher and board chairman Larry Flynt frequently off fighting his own personal battles, those in charge at the Los Angeles headquarters ruled the roost with a barrage of tough-talking memos on topics ranging from office pranks and missed deadlines to security worries.

It all came back to me recently, like an uneasy dream, when I ran across a trove of “inter-office memos” I’d saved from my three-plus years as a Hustler editor. Perusing these ancient, pre-email, pre-internet missives—many typed on letterhead with the magazine’s name emblazoned in huge letters at the top, then distributed to each recipient by hand—I recalled the weirdly paranoid ethos that often suffused the place.

The atmosphere might have been driven by a certain illicit drug some of us had in our desk drawers, or by the five or six scotch-and-waters it could take to decompress each night. Or maybe it was fueled by tensions between the “old guard” editors from Larry’s Ohio days—he’d launched the publication there in 1974—and the newbie Californians on staff, including me.

But it definitely was influenced by the higher-ups’ striving to please the mercurial wheelchair-user Flynt, whose spirit loomed large in the place despite his physical absences. Hustler had a reported circulation of about 1.4 million in the fall of 1980, when I joined Larry Flynt Publications Inc. at age 31 after responding to a classified ad in the Los Angeles Times seeking an associate editor. I’d landed the job after writing a test piece for the publication’s regular “Asshole of the Month” column. Soon I found myself reporting for duty to Hustler’s swank offices on the 38th floor of Century Park East, one of the Twin Tower buildings at L.A.’s ABC Entertainment Center.

I quickly learned that strict adherence to deadlines was a big deal at the monthly magazine (as indeed it was, and is, at most publications). The content may have been raunchy and freewheeling, but, in this memo, Hustler’s managing editor let us know it all had to be submitted on time:

Friends and colleagues, imagine the consternation of your Man Ed when upon his return to duty he finds, with precious few exceptions, members of the editorial staff are not meeting their deadlines. More disturbing, there seems to be a devil-may-care attitude about internal deadlines, as though they were some petty plot hatched by a fiend. The fact of the matter is—take note—these internal deadlines are to be regarded as scripture. Basic professionalism dictates that you all meet your deadlines. Do it. The new policy here will de-emphasize human rights and concentrate on the terrorism of missed deadlines. If any September deadlines are missed, I’ve already thought up all kinds of nasty little things to do to the guilty parties.

One of my early assignments had me editing the magazine’s X-rated movie review feature. In addition to a written review, each “erotic film” was given one of five graphically illustrated ratings: Erection (“A constant turn-on. If this won’t get you up, you may be dead”), Three-Quarters Erect (“Worthwhile. Almost gets it up. But it can still be beat”), Half Erect (“So-so. Probably gets it up with a little help from your fist”), One-Quarter Erect (“A poor turn-on. Just might get it up if you used a crane”), and Totally Limp (“A turn-off. This one couldn’t get it up if you used a crane”).

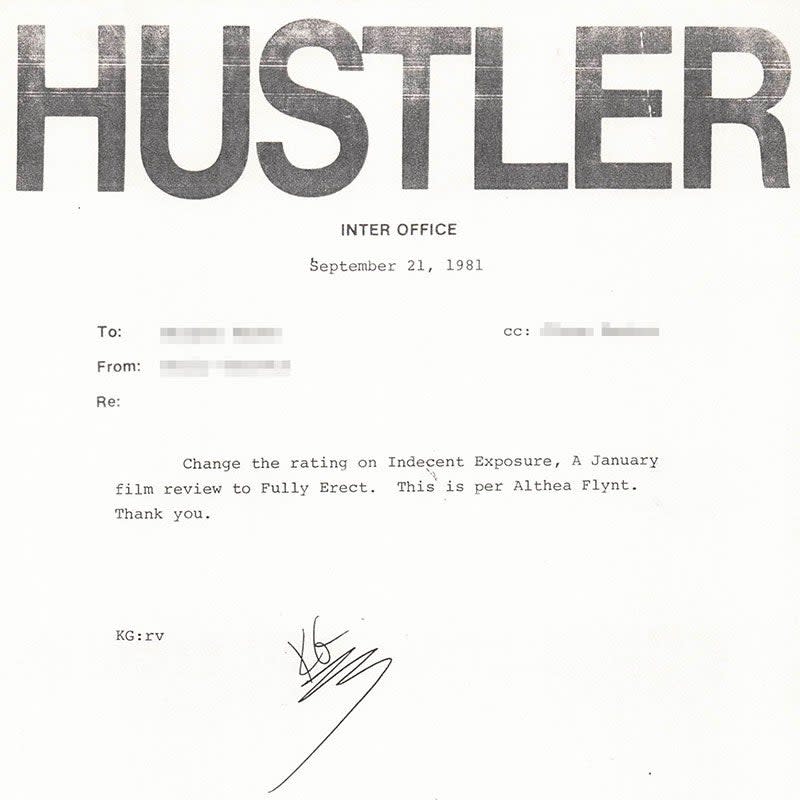

Larry’s then-wife Althea Flynt, Hustler’s president and associate publisher, took a keen interest in these reviews. That’s clear from this missive from the managing editor to the copy chief, which confirmed the universal fear editors have regarding meddlesome publishers:

Change the rating on Indecent Exposure, a January film review, to Fully Erect. This is per Althea Flynt. Thank you.

Hustler and its reviews were popular in the porn-film community, which included the moviemakers as well as actors like John C. Holmes (aka “Johnny Wadd”). In 1981 Holmes was arrested and charged in connection with the so-called Wonderland murders of four people in Hollywood’s Laurel Canyon. His situation led me to write this to Althea:

Julia St. Vincent, who produced the new John Holmes documentary Exhausted, called today saying that Holmes has requested a HUSTLER subscription to help him pass the time at the L.A. County Jail. She asks that we bill her for a one-year subscription at Freeway Films. The subscription itself should be addressed to John Holmes, L.A. County Jail, 6413230-Section 1700, Terminal Annex, P.O. Box 54320, Los Angeles, CA 90054. Thank you.

Another of my assignments was editing a Hustler feature called “Beaver Hunt.” Women submitted nude photos of themselves that left nothing to the imagination, and, if they were lucky enough to make the cut, received $50 in return. Along with the photo, they also provided some detail about their lives and aspirations, which we turned into copy like this: “A 32-year-old factory worker from Commerce City, Colorado, Gina lists her hobbies as sex and painting. She fantasizes about making it with Neil Diamond.” Since all elements of each entry were fact-checked by the magazine’s research department, this interoffice memo to that department naturally caught our eye:

Please be advised that an attorney for [REDACTED] has notified us that a photo of his client may be fraudulently submitted to us for publication, presumably in Beaver Hunt, under any one of [REDACTED]. Please be on the look out for such a submission and should it surface, notify the Law Department.

Much of the time, the company’s top executives seemed preoccupied with policing the staff for infractions ranging from “tardiness” to sophomoric pranks. Take, for example, this message to employees from the editorial director:

Lately there have been a number of situations where staff members have been going into other staff members’ offices when they are not there—be it for business or for some sort of practical joke. I absolutely will not tolerate this sort of behavior. There have been several instances where money has been missing and property has been taken from offices. As for pulling appliance plugs out of sockets, there is no place for this type of childish behavior at LFP. I want this behavior to cease immediately.

Althea weighed in on staff transgressions as well:

It has been brought to my attention that tardiness is rampant in our department. Everyone from secretaries, talent, photo, to art departments are abusive. I expect this to be corrected immediately or new personnel will be replacing those that can’t maintain office hours.

In contrast to the magazine’s no-holds-barred content—and to its sometimes hard-partying staff—Althea developed an unironic interest in Hustler’s corporate image as projected in outgoing correspondence. She also told people where to eat their lunch:

The image of a corporation is reflected in the style, tone, and format of its correspondence. Corporate letterhead and stationary must be used on all outgoing correspondence and should be prepared in Full Block or Block Style. To save time and handling, as well as for spot-checking for personal correspondence, please do not seal any envelope. The mail handlers will be responsible for sealing and posting all outgoing correspondence. Additionally, the sender’s name should be typed in the upper left-hand corner of the mailing envelope. Additionally, no food is to be eaten at your desks, a canteen is provided for that purpose.

Hustler’s volatile publisher and board chairman, who was paralyzed from the waist down after being shot in 1978 outside a Georgia courthouse, was also concerned about the magazine’s image. He sent this memo to “All Employees”:

At approximately 1:00 p.m. on Wednesday, December 15, KNXT-TV, Channel 2, will be in our offices filming a segment for “Two on the Town.” I would like everyone to be dressed appropriately for the occasion and conducting themselves in a professional and businesslike manner because they will be filming in the offices.

Sometime thereafter, Larry wore an American flag as a diaper for a federal court appearance.

Meanwhile, using company time to work on outside projects was verboten, the editorial director explained, and no offender would be able to escape his watchful eye—or his iron fist:

It is a clear matter of company policy that LFP employees are to spend their office hours working only on company-related projects. I want to underscore the seriousness of this policy to all of you. Violation of this recently resulted in the termination of a Department Supervisor—a long-time employee. That termination should serve notice that I will broach no violation of this rule by any employee. For the benefit of those who lack the ability to read between the lines, there is little that occurs in this company that does not eventually make its way to this office. Future violations will be dealt with by sure and predictable action.

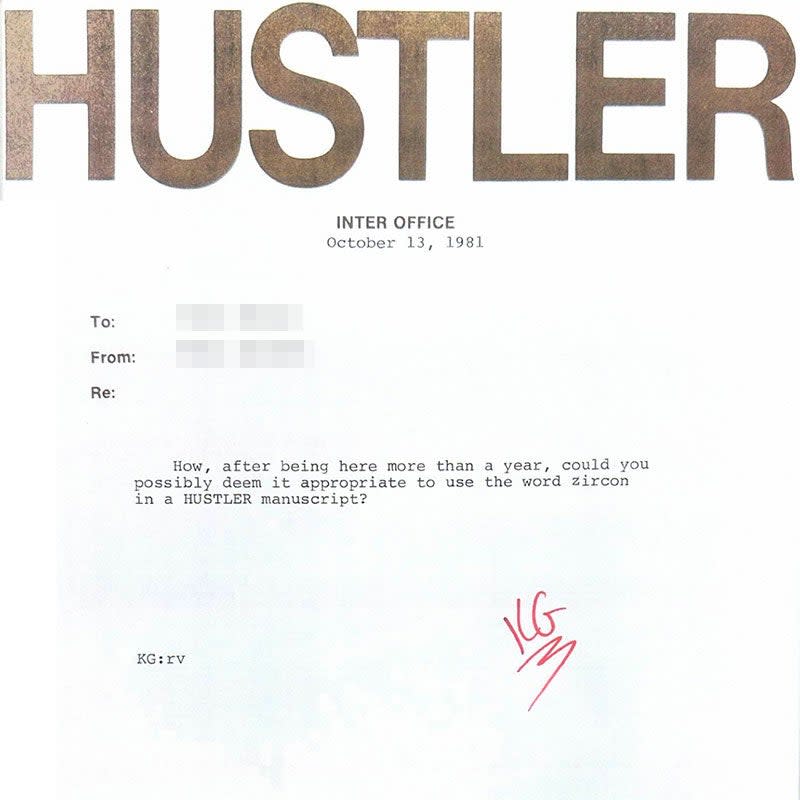

As you would expect, enforcing the magazine’s editorial guidelines—always with the reader in mind—was important to the top executives. Hustler’s target audience consisted of blue-collar, Joe Sixpack types, as my supervising editor alluded to in this message:

How, after being here more than a year, could you possibly deem it appropriate to use the word zircon in a HUSTLER manuscript?

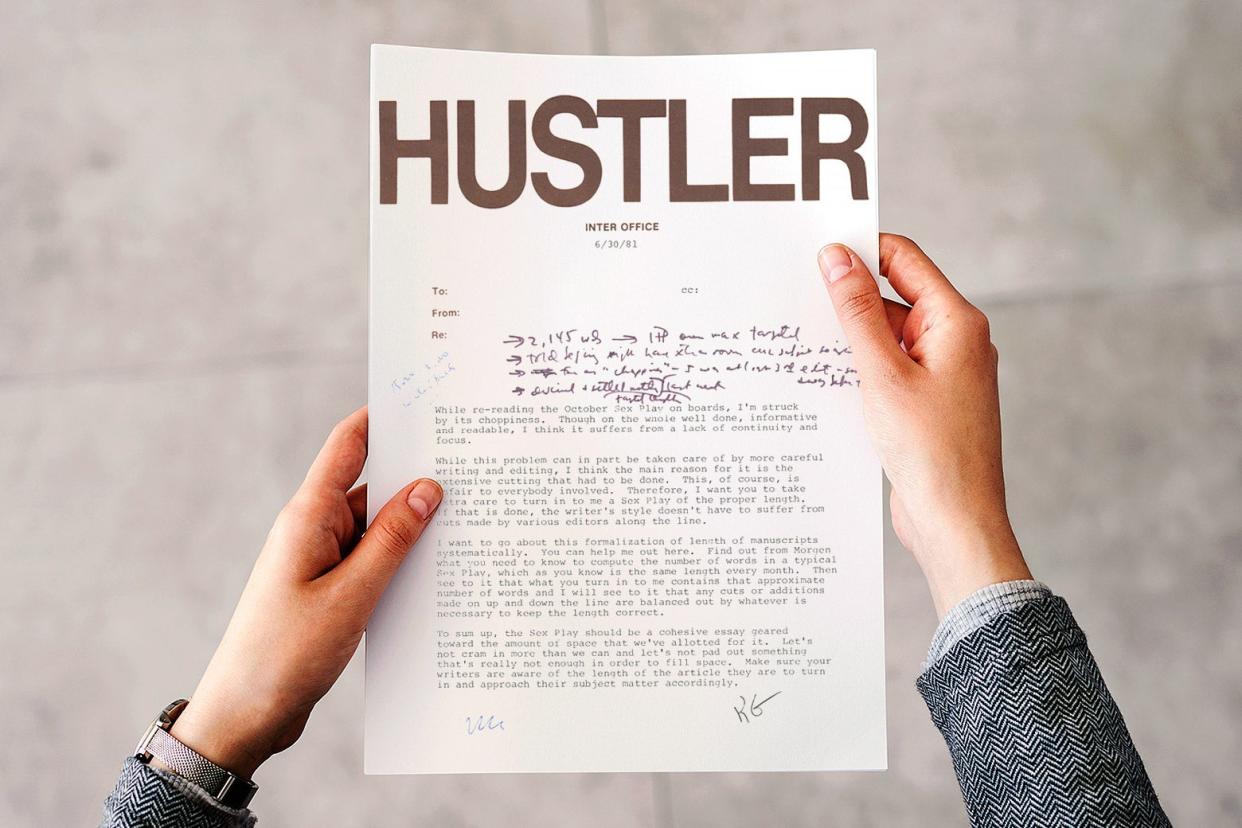

He also chided me on occasion for the way I’d edited articles:

While re-reading the October “Sex Play” on boards, I’m struck by its choppiness. Though on the whole well done, informative, and readable, I think it suffers from a lack of continuity and focus. I think the main reason for it is the extensive cutting that had to be done. Therefore, I want you to take extra care to turn in to me a Sex Play of the proper length. If that is done, the writer’s style doesn’t have to suffer from cuts made by various editors along the line.

The writer of the piece, who’d been copied on the previous memo, soon replied with one of her own:

I find it hard to believe (with all due respect) that you do not realize that when 3 editors ask for up to 700 words in additions to an article and only see one cut that you do not realize that you are going to come out with a very long article needing cutting. Specifically on my Sex and Violence piece, you told me you thought the Blacks article wasn’t good so you were going to cut it and have mine run longer. So I didn’t worry at the time. Then this was not done so the piece was cut drastically and weakened. But it is beyond adding insult to injury when I go over a memo like yours. I feel like we are damned if we do and damned if we don’t.

In the 1980s, as now, companies routinely let employees go and assigned their workloads to others, often without compensating pay. When I inherited jobs editing both the movie reviews and a regular books column by Theodore Sturgeon, a well-known science-fiction writer, I asked the editorial director whether I might be paid for the additional work. This was his response:

To begin with you may be laboring under a misconception. The primary reason that [NAME REDACTED] was dismissed was because it was my feeling that his position was a rather superfluous one. Certainly Sturgeon’s work needs very little editing since his reputation as book reviewer for the New York Times in the past is one of considerable repute so [REDACTED] was not so much dismissed in a consolidation attempt rather than one of the job being superfluous. I do not know who mentioned to you that more money would be forthcoming in March, whoever did mention that to you I’d like to discuss the matter with them since it certainly was not cleared through my office and definitely it was not broached with Althea or Larry Flynt. As far as determining what would be a reasonable increase, that decision rests primarily with myself and the Flynts and certainly not with you.

The U.S. economy was enduring its worst recession since the Great Depression in the early ‘80s, and Hustler’s business suffered along with the rest. The poor results led the company executives to implement a series of cost-cutting measures, telling the staff:

As subscriptions to our magazines run out, we will not be re-subscribing. However, this does not mean that you are not to keep informed of world, national, and local events. I expect you to purchase whatever magazines or publications you need to fulfill your job, on your own.

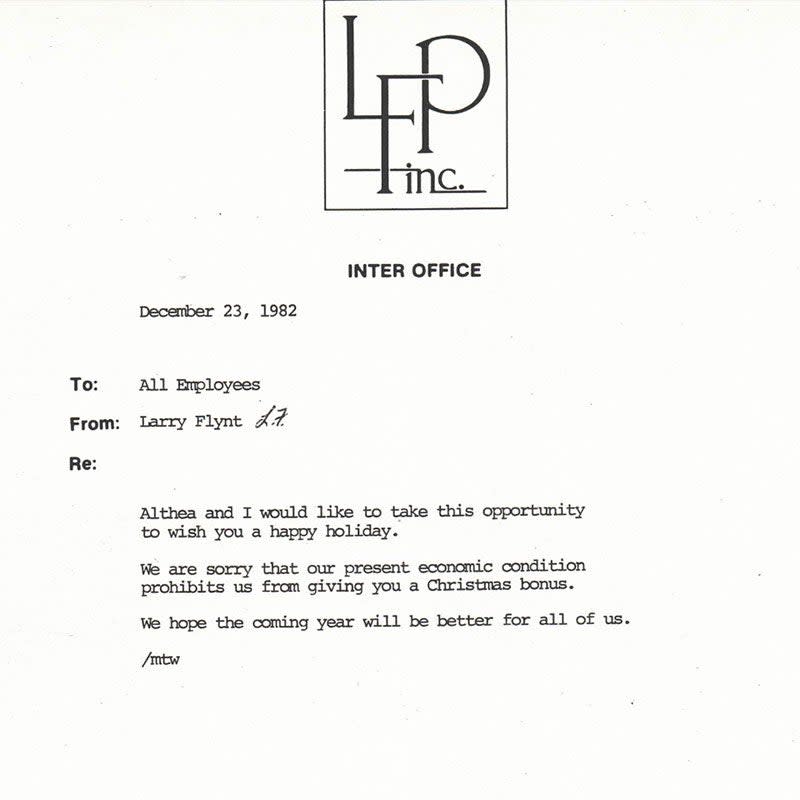

Larry himself recognized the pain in two separate messages to all the employees:

As part of LFP’s austerity program we will no longer pay for time off in observance of religious holidays. We do, however, recognize your need to observe and participate in religious practices and will make every effort to accommodate you with the necessary time off. Earned vacation time may be applied if you desire.

Althea and I would like to take this opportunity to wish you a happy holiday. We are sorry that our present economic condition prohibits us from giving you a Christmas bonus. We hope the coming year will be better for all of us.

A dramatic last word on the company’s “austerity” campaign came from the editorial director, whose claim to fame outside the Larry Flynt Publications world had been writing a bestselling murder mystery:

As you all know, we have made a number of staff reductions in recent weeks. One of those reductions has been in the Security Department. As a result, our security is limited to after normal working hours. I have noted a number of problems cropping up in the last few weeks related to this lack of uniformed guards on the floor. On more than one occasion I have noticed side doors which are propped open with scissors or staplers—presumably so people may use the bathroom or visit another office and then re-enter through the side door. Several times there have been unauthorized people on the floor, visiting with friends. It may be humorous to some of you to read of these incidents. Indeed, they seem to be insignificant and to carry little cause for concern. The time may come, however, when there is cause for concern. The time for concern is when you see a stranger roaming the floor and you assume it’s just someone visiting a friend, when the only friend the stranger has is the .45 tucked in his waistband. If you see someone on the floor who is acting strangely—aside from our editors, of course—notify security immediately.

Whether due to better opportunities, frustration, or the aforementioned “staff reductions,” LFP staffers inevitably moved on. Several of my colleagues went on to produce or write for major network TV shows or hit Hollywood movies. And after quitting once following a disagreement with Larry—only to return later and have him fire me along with other editors—I became a reporter and editor for newspapers and business publications.

It’s safe to say the time we spent at LFP, while often bizarre, toughened us up for our future endeavors. After surviving the rigors of Hustler magazine, I’d forever see even the most challenging workplace as a walk in the park.