'For the Record': See a film that documents the last days of one rural Texas newspaper

If you love newspapers — and since you are reading this column, I hope you do — "For the Record" is hard to watch.

The new documentary by Heather Courtney records the agonizing decline of the award-winning Canadian Record, a weekly newspaper in the Texas Panhandle that folded March 2, just months after the movie was completed.

At 7:30 p.m. on April 13, the public can see the movie for free during a screening at the International Symposium on Online Journalism, held at the AT&T Hotel and Conference Center on the University of Texas campus. Attendees must reserve a spot in advance via Eventbrite; go to bit.ly/for-the-record-isoj.

The film's producers, which include distinguished documentary maker and UT professor Paul Stekler, hope to make it available through a streaming service soon.

More:'And Still We Rise': Exhibit at Galveston's new Juneteenth museum tells powerful history

The Record served the community of Canadian (population 2,649), located in the Panhandle about 100 miles northeast from Amarillo. It's a beautiful, windy place, perched above the canyons of the Canadian River, a tributary of the Arkansas River. Agriculture along with the oil and gas industry underpin much of the local economy.

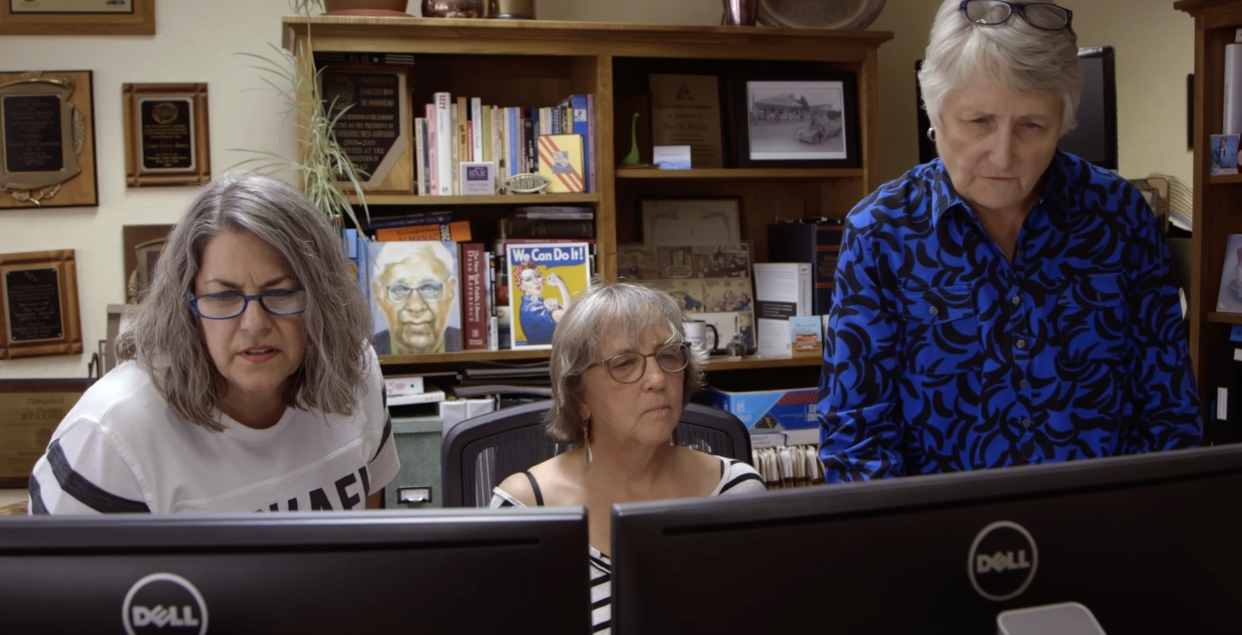

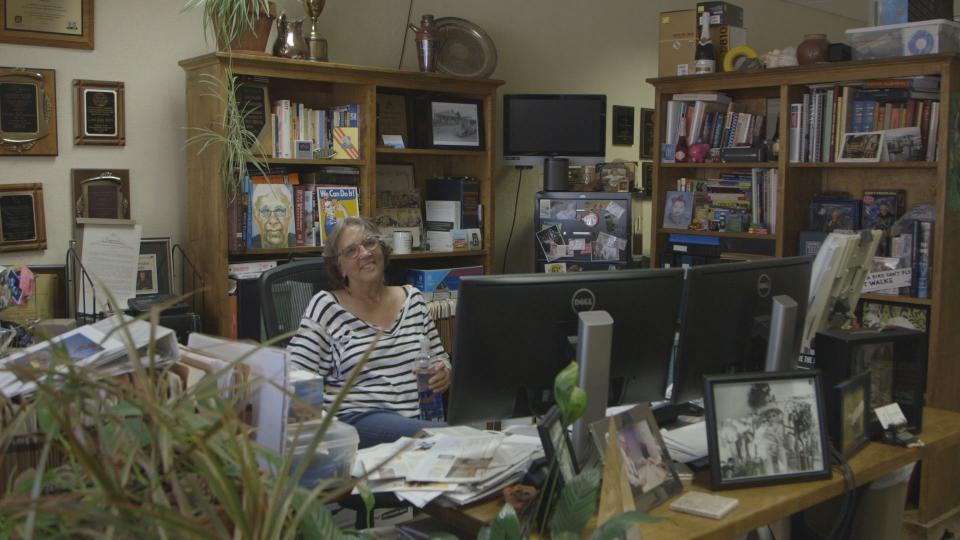

Intermittently from 2019 to 2022, Courtney followed the daily routines of Laurie Ezzell Brown, publisher and editor of the family paper (circulation 1,613), and those of her employees. The Record was founded in 1893 and was purchased by her parents, Ben and Nancy Ezzell, in 1947.

It was a family affair.

In the movie, Brown interacts constantly with the local community to cover events large and small. Almost always, the Record is the only media outlet to report the news in person.

During the newspaper's last months, Brown did much of the journalism virtually on her own. On March 2, she retired.

"The decision was fueled by several factors," Brown told the American-Statesman last week, "including a diminishing staff, the difficulty of hiring new employees in a community that is relatively isolated, and my growing exhaustion with the increasing workload, the long hours with little sleep, and the impossibility of ever taking a break."

Brown had hoped that her son, Gabriel Brown, a coffee roaster, would take over the family business. Yet judging from the scenes recorded in the movie, she would never push that option on him. And Gabriel, who watched how his grandparents and mother were consumed by the news business, would never take her up on it.

Brown still hopes to find a buyer for the paper.

The last years of the Record?

This documentary, which packs a lot of facts and feeling into a short 35 minutes, is not just about the Record. Throughout the film, Courtney reminds the viewer that rural newspapers, often the only source of local news in small towns, are crumbling to dust.

"Since 2005, more than a quarter of all newspapers in the U.S. have closed," reads a movie intertitle. "Over 20% of Americans live in news deserts without any local news source."

We see the Record journalists doing all the crucial jobs — reporting, writing, editing, photographing, designing, engaging readers one-on-one — that dozens or more journalists might do in a big city paper.

More:Texas literary legend Larry McMurtry's personal estate up for auction in San Antonio

As a photojournalist, among her others duties, Brown also captures the dramatic Panhandle weather, the scourge of wildfires, and the changing of the seasons, as well as the familiar rituals of rural life.

"A bad day starts about 2 o'clock in the morning," Brown says in the movie. "A good day probably starts at 4. No one else is going to tell the stories that we're telling. Nobody. There's all these things that we do on a daily basis that I don't know who's going to do if the newspaper doesn't. What happens if nobody's doing this?"

I suspect that many journalists, as well as readers, will choke up more than once during this movie.

Courtney catches the newspaper folks, especially Brown, out in the community at public meetings, ball games, parades, picnics, rodeos, livestock shows, groundbreakings, church services, ribbon cuttings, political rallies, business conferences.

Brown is smart, funny, likable, gentle, stubborn, hard-working and appears to get along easily with her lifelong neighbors.

Time and again, members of the community thank Brown on camera for her diligence and for her editorials on practical problem solving, such as a campaign for a badly needed new nursing home in Hemphill County, and against taxpayer incentives for a corporate pork processing facility.

This gratitude is palpable, despite the fact that Brown's editorials about larger cultural and political matters — such as COVID-19 reporting and precautions — went against the social grain in a county that voted for President Donald Trump by an overwhelming margin in 2016.

She was lobbied, for instance, to delay reporting on President Joe Biden's win in 2020.

More:These Texas wildflowers 'transcend time' at Lady Bird Johnson Center

Despite this gap, people in Canadian — who often stopped by the newsroom to pick up their $1.50 papers personally — understood that the Record was a lifeline. Not just for understanding what was going on in town and how its culture came to be, but just as importantly, for holding public officials to account.

Brown is no ideologue. No journalistic bomb-thrower. Her editorials are reasoned and responsible. She starts with common ground and tries move the needle of opinion one notch at a time.

Given the setting, however, her editorials are courageous, and they have been recognized by advocates of public service journalism across the country.

From the same editorial desk, Brown's father supported the Civil Rights Movement and opposed the Vietnam War. He also exposed the antidemocratic tendencies of the John Birch Society. He received threats. During her youth, a small bomb was set off under Laurie's window.

What appears to disorient and disturb Brown — and much of the rest of America — is how willing people have become to deny the basic facts and truths that newspapers report on a daily basis, well away from the opinion pages.

What the world should know

Anyone who pays attention to current events knows what has happened to newspapers — online and in print — during the past two decades.

Together, we've watched advertising migrate to other platforms. Papers have thinned, and newsrooms have grown smaller. Covering all the news that's fit to print is no longer viable even in big cities, except for a few well-financed national outlets.

The pandemic and its attendant business quarantines dried up much of what was left of local advertising, at least for a while.

More:Good reads about Texas: A San Marcos book club plunges into literature about the state

Yet newspapers small and large continue to land big stories and to share critical insights into who we are. They have not given up on the idea that their communities need the press.

Nor have readers.

Brown: "People come to me all that time and say: 'Please don't ever stop doing this.'" I've heard the same thing — almost daily — from our readers.

Others are paying attention: Following the April 13 screening of the film, Kathleen McElroy, former chairwoman of UT’s School of Journalism and Media, will lead a panel chat about the future of community newspapers with Laurie Brown, movie director Heather Courtney, author Bill Bishop (formerly of the American-Statesman) and Al Cross (director of the Institute for Rural Journalism at the University of Kentucky).

"It was with great difficulty that I made the decision to suspend publication," Brown told the Statesman. "I love this community and the work I have done for the last 30 years as editor, and before that, in several other roles alongside my parents.

"I believe deeply in the value of a good, independent newspaper, particularly in rural communities, and am actively seeking someone who feels as strongly as I do and who values the rich rewards that accrue to both reader and publisher."

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@gannett.com. Sign up for the free weekly digital newsletter, Think, Texas, at statesman.com/newsletters, or at the newsletter page of your local USA Today newspaper.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: How to see For the Record film in Austin, about a Texas newspaper