Records reveal feds misled Tanzanian police after US citizen killed woman in Africa

Immediately after a Peace Corps employee in Tanzania went on a reckless drunk driving spree in 2019 that left one woman dead and another badly wounded, police in Dar es Salaam initiated an investigation that could have put the U.S. citizen behind bars overseas.

But U.S. State Department officials acted fast to thwart their efforts to hold John Peterson accountable, according to hundreds of pages of documents obtained by USA TODAY.

The records show Dar es Salaam police tried to give Peterson a breathalyzer test but gave up after a U.S. embassy security official asserted that Peterson’s diplomatic immunity exempted him from such testing. Peterson, however, did not have diplomatic immunity.

Police released Peterson from custody and directed him to return to the police station two days later. Instead, U.S. embassy officials that same day put Peterson on a plane and waited to inform their counterparts in Tanzania of the incident until after the plane had left.

“Once they are airborne, I will notify” Tanzania’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the top U.S. official at the embassy in Dar es Salaam, Inmi Patterson, wrote in an email to staff and State Department central operations. “We would have to handle their reaction/consequences then.”

The State Department and Peace Corps records USA TODAY obtained provide the most complete accounting yet of how U.S. officials spirited Peterson out of Africa and of the destruction Peterson caused on the streets of Dar es Salaam after he brought a sex worker to his government-leased home.

With Peterson back in the United States, the records show State Department and Peace Corps investigators put months into building a potential criminal case against Peterson as they tracked down eyewitnesses, interviewed Peterson’s security guard and colleagues, and even tried to calculate the ounces of sauvignon blanc he drank. Investigators also questioned Peterson — fresh off the plane from Tanzania — who tried to convince them the sex worker in his vehicle was just a friend and that he drank only two glasses of wine before the crash, even though multiple witnesses said he appeared intoxicated.

And yet the thorough investigation resulted in no charges in Tanzania or the U.S. against Peterson, 68, who resigned from the Peace Corps 18 months after the incident. His responsibility for the death of Rabia Issa, a 47-year-old mother of three whose family received a meager cash settlement from the U.S. government, had been hidden from public view until USA TODAY first reported on the case last year. Much of the State Department’s role in helping Peterson dodge accountability in Tanzania remained untold until now.

State Department officials declined to be interviewed for this story. After providing the documents to reporters, an agency records specialist said portions had been improperly released without approval of the Peace Corps and asked USA TODAY to destroy them. USA TODAY declined the request.

Vedant Patel, a State Department spokesman, blamed the confusion over Peterson’s immunity on a diplomatic identification card Peterson had been issued by the Tanzanian government. Patel wrote in a statement that embassy staff who responded to the crash were not trying to deceive local authorities

"There was never, at any time, any effort on the part of the United States to deliberately mislead Tanzanian authorities as to Mr. Peterson’s diplomatic status,” Patel said. “Any statements made by Embassy security officials to local authorities in the immediate aftermath of the incident concerning Mr. Peterson’s status were based on the information available at the time — specifically Mr. Peterson’s Government of Tanzania-issued diplomatic ID card.”

In more than 300 pages of State Department records about the incident — including detailed accounts from the officials who responded to the crash site — there is no mention that Peterson showed embassy staff or local police a diplomatic identification card. Even if he had, Peterson did not have diplomatic immunity, a privilege included in the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations that is meant to protect diplomats and their families from unfair punishment in foreign justice systems. Peace Corps employees are not typically granted that exemption.

State Department officials justified Peterson’s hasty departure from Tanzania as medically necessary, saying he needed surgery on his injured hand. But even two months later, embassy officials stonewalled Tanzanian police who contacted the Peace Corps seeking clarity on Peterson’s non-existent immunity status. Emails show a top State Department official cautioned against sending a response, noting that the Tanzanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs had yet to follow up about the crash. “And that is frankly a good thing,” Janine Young, then the Acting Deputy Chief of Mission in Dar es Salaam, wrote.

James Gathii, a professor of international law at Loyola University Chicago and Vice President of the American Society of International Law, said embassy officials should have known Peterson did not have immunity. He said the fact that U.S. officials waited until Peterson was out of the country to contact the Tanzanian government suggests they knew they were helping him evade justice.

“Rules of international law are supposed to be applied in good faith, and this is a very good example of, in my opinion, lack of good faith on the part of those officials who made the decision to spirit him away before contacting the government of Tanzania,” Gathii said. “They preempted any questions the government of Tanzania might have raised if they had contacted them first.” Peterson, who worked for the Peace Corps on and off since serving as a volunteer in 1977, declined to comment through his attorney, Mark S. Zaid. In a statement, Zaid said there “are several misleading inaccuracies” in the Peace Corps and State Department records, but he did not elaborate. He added that the decision to evacuate Peterson from the country was “nothing outside of the norm” and consistent with government policy and practices. Peace Corps CEO Carol Spahn, who was nominated earlier this year to lead the agency as a Senate-confirmed director, has repeatedly declined interview requests about Peterson. Peace Corps spokesman Troy Blackwell said in a statement the agency does not have the authority to assert diplomatic immunity and that officials will cooperate if Tanzanian authorities decide to charge Peterson. The Department of Justice, in a November 2019 letter, also noted that Peterson does not have immunity and said the agency will consider any extradition requests “in accordance with our legal obligations.”

Tanzania President Samia Suluhu Hassan’s office, the country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Tanzanian police did not respond to questions from USA TODAY. Gathii said the power imbalance between the two countries could have influenced how both governments responded to the incident. Tanzania, an East African nation that receives more than $300 million annually in U.S. aid, at the time had a strained relationship with the U.S. that Hassan has sought to improve since taking office in 2021. “Governments that are recipients of a lot of donor support from governments like the U.S. are unlikely to ruffle feathers when this type of diplomatic scuffle arises,” Gathii said. “The officials may calculate that they have more to lose by trying to play by the rule book than not.”

New details emerge about deadly crash

The government documents include a 144-page transcript of an interview with Peterson, witness summaries and internal emails sent after the crash. Despite extensive redactions and some conflicting witness accounts, the records give the clearest picture to date of the chaos and extensive damage Peterson caused on the morning of August 24, 2019.

Shortly before 5 a.m., Peterson drove a sex worker from a home the U.S. government rented for him in Dar es Salaam back to the neighborhood where he had picked the woman up earlier that morning. Peterson and his passenger later told investigators that a female pedestrian suddenly jumped in front of Peterson’s Toyota Rav4. The woman was “crushed and severely injured,” according to a letter from Tanzanian authorities.

An angry crowd gathered and banged on the car. Peterson said he took off and planned to drive to the nearby U.S. embassy before instead turning towards his home. Motorcycle taxi drivers tailed behind. Witnesses said police also pursued, though Peterson later said he did not see them.

The drivers caught up with Peterson at a red light, and several laid down their motorcycles in the street to block him. One person smashed in Peterson’s window, and Peterson drove over the bikes in the road as he sped off. Investigators later heard that Peterson may have struck and injured one of the taxi drivers, but the records do not say if they ever identified this person.

Charles Mbunga, a local business owner, was standing near his roadside shop when he saw Peterson’s vehicle approaching. Nearby, a single street-food vendor had arrived before sunrise and was tending to a fire.

Mbunga watched helplessly as Peterson drove off the road and struck the woman, Issa. Her body flew over the hood of the vehicle.

As he drove off, Peterson smashed through a fence and roadside stands. He continued about half a mile further before his vehicle slammed into a light pole and came to a final stop.

A brief detention and hasty departure

Within roughly 30 minutes of the crash, several State Department employees had arrived at the scene, where a crowd of angry onlookers and police officers gathered around the vehicle. A tow truck repeatedly lifted and dropped the mangled Toyota Rav4 while Peterson — soaked in blood with the airbags deployed around him — was still inside. Issa’s brother reached through the window and punched Peterson in the face.

One State Department employee, a security officer whose name is redacted in the records, approached the SUV and noted that Peterson was “very calm and did not appear to understand the severity of the collision nor the accusations of several pedestrians being hit,” according to the records. He persuaded Peterson to get out of the vehicle and noticed the stench of alcohol and Peterson’s bloodshot eyes, unsteady footing and slurred speech.

As Tanzanian police swarmed to take Peterson into custody, the security officer said that Peterson was an accredited diplomat who was willing to cooperate with police but needed to go to a hospital first, according to the records. The police nevertheless hauled Peterson into the back of a police truck and allowed the embassy official to climb in behind.

On the way, Peterson asked if he had killed someone. The security officer didn’t answer.

The truck stopped amid another large and volatile crowd. The doors opened, and police loaded Issa’s lifeless body into the truck bed, beside Peterson.

At the police station, Peterson and the security officer were joined by at least three other embassy employees, including a doctor. Tanzanian police prepared a breathalyzer test — even shoving the tube into Peterson’s mouth while he resisted — but the U.S. embassy staffers asserted that Peterson was an accredited diplomat who did not have to comply, records show. As the embassy security officer began to explain the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, the police officers laughed but then told Peterson he was free to go. They directed him to return on Monday, two days later.

Peterson was taken to a local hospital where he said a doctor assessed his injured hand and recommended he have surgery within 24 hours.

On a conference call, embassy officials met with representatives from several State Department offices, part of a flurry of activity as the agency scrambled to address the early-morning chaos.

“Please if you could advise further if you have any concerns with his diplomatic status or immunity,” Young, the acting deputy chief of mission in Tanzania, wrote in an email. She added that because Peterson needed surgery, they wanted a medical evacuation back to the U.S., “but understand the legal implications as well."

The records show that numerous people within the State Department, in the hours after the crash, operated under the assumption that Peterson had diplomatic immunity. But one person at the embassy did catch the mistake before Peterson left Tanzania.

“One point of clarification,” an embassy security officer emailed to an agency investigator and other individuals whose names and were redacted from the records. The officer said Peace Corps staff in Tanzania did not appear to have immunity.

The revelation did not prompt a change in course. Peterson returned home from the hospital to pack his bags and the same day boarded a flight, according to the records. Inmi Patterson, who as the chargé d'affaires was the highest-ranking U.S. official at the embassy, notified State Department central operations that she would contact the Tanzanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs once Peterson’s flight was in the air.

“Please confirm when Mr. Peterson is wheels up,” the operations center wrote.

At 6:30 p.m. — roughly 13 hours after Peterson killed Issa — Young sent her reply.

“Wheels up at 1821,” she wrote.

Young, who still works for the State Department, and Patterson, who stepped down from her position at the embassy in 2020, both declined to comment when USA TODAY contacted them about the incident.

Two days after Peterson left Tanzania, State Department officials drafted a letter to the Tanzanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that again claimed Peterson was an accredited diplomat protected under the Vienna Convention. It said the U.S. government had not waived Peterson’s privileges and immunities, records show. State Department spokesman Vedant Patel told USA TODAY that the letter was never sent but offered no further explanation. Ned Price, another agency spokesman, said Inmi Patterson verbally notified the ministry of the incident and of the medical evacuation but that there was no discussion of Peterson’s immunity.

Police in Dar es Salaam, however, remained interested in Peterson’s immunity status and in October 2019 sent the local Peace Corps office a letter seeking clarity on the matter.

We “need to know if the driver had Diplomatic Immunity and which type of immunity,” a police official wrote.

The police followed up in person at the Peace Corps office a few days later, emails show, and the Peace Corps general counsel’s office drafted a reply. Janine Young, at the embassy, advised against sending it.

“Janine - I understand the plan is to hold off on responding to the letter for the time being,” a person, whose name is redacted in the records, replied. “That is ok with me. I would just ask that there be no informal follow up with the local authorities on their request, particularly on the immunities issue, unless we have had a chance to touch base further.”

“We agree,” Young wrote back, saying that her staff had “no intention of saying anything formally or informally” regarding Peterson’s immunity.

'I asked you how much you had to drink'

Minutes after landing at Washington D.C.’s Dulles International Airport, Peterson was greeted by two federal agents from the State Department Office of Special Investigations and Peace Corps Office of Inspector General. Peterson, who was headed to the hospital, agreed to be interviewed but said he hoped it would be quick.

The tape recorder ran for 2 hours and 14 minutes.

After being read his Miranda rights, Peterson told investigators he was driving when a woman darted into the road and in front of his vehicle. He said he fled because he feared for his safety and then lost control of his vehicle as motorcycle drivers pursued. Asked what he had done in the hours before, Peterson said he went to a pub shortly before midnight where he ordered a fish dinner and two glasses of sauvignon blanc. The investigator from the State Department, who in the records is referred to as Agent Nelson, homed in on Peterson’s drinking.

The transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

AN: “I know it is, um, and I know you had probably had more to drink than what you're tellin' me. I get it. I was a cop for years and everybody had two drinks. … I'm just tryin' to figure out how much that affected your recall from that night from the accident.”

At least 33 times in two hours, the agents asked Peterson how much he drank — though their counterparts in Dar es Salaam had failed to breathalyze Peterson the day before. Peterson repeatedly said he only had two glasses of wine. The agents told Peterson that witnesses at the scene believed he was intoxicated. They asked if he had anything to drink before going out, or whether the bar had unusually large pours. The agent from the Peace Corps Office of Inspector General, John Warren, asked Peterson to draw a to-scale picture of the wine glasses the bar used.

Warren finally reasoned that it would look better for Peterson if he had been drunk, because the alternative was that he deliberately ran someone over while sober.

Peterson later acknowledged ordering up to four drinks and indicated he would have been over the U.S. legal limit to drive.

The agents also asked Peterson about the woman in the car with him. Peterson said she was just an acquaintance he ran into at the restaurant where he had dinner.

Pressed for specifics, Peterson said he didn’t recall the woman’s name. Though the agents would not identify and interview the sex worker for five months, Nelson bluffed and told Peterson that an Embassy security official in Dar es Salaam knew the woman and "probably already interviewed her."

Nelson said he knew Peterson lived alone and far from his wife and wouldn’t blame him for seeking out companionship, assuring him that “everybody's got a little dirt in their closet.” Peterson ultimately acknowledged paying the woman for oral sex and to bringing other sex workers to his home. With that crack in Peterson’s initial account, the agents pressed Peterson again on other details, including the car chase through Dar es Salaam and the final crash.

As Peterson again recounted the events, Nelson pointed out how “unusually calm” he was, considering the circumstances. Others who interacted with Peterson in the hours after the crash would make the same assessment, saying Peterson was remarkably composed.

That, perhaps, is because he did not grasp the gravity of what he had done.

Peterson appeared to have no recollection of striking Issa, the mother whose body had been loaded beside him in the police vehicle the day before.

Over the next few months — as Peterson was on paid administrative leave — State Department and Peace Corps employees interviewed an array of people in Dar es Salaam: Peterson’s housekeeper, eyewitnesses along his route, employees at bars he might have visited and two women who said Peterson had paid them in exchange for sex. They investigated Peterson on the allegations of vehicular homicide, driving under the influence, engaging in prostitution and providing false statements.

None of the Peace Corps or State Department reviews of the incident appear to have focused on the decisions surrounding Peterson’s immunity and evacuation.

The guard who worked at Peterson’s home in Dar es Salaam told a security official he had seen Peterson appear drunk several times and noticed whiskey and wine bottles put out with the trash. He also said he was used to seeing various young women come and go from the home — in Ubers, on foot, or in Peterson’s vehicle after a night out.

He said Peterson asked him to not record female guests in the visitors log. But on the morning of the fatal crash, Peterson pulled into his gated compound at 3:13 a.m. and a slender Tanzanian woman got out of his vehicle, pulling at the little clothing she was wearing in an attempt to cover herself. The guard added the guest to the log. Peterson, he noticed, appeared to be drunk. The guard made another entry when the two departed at 4:50 a.m.

About five months after the incident, an investigator finally spoke to the woman who was in the car with Peterson. The sex worker said she met Peterson that morning while she was standing on the side of the road and calling out to passing cars, not at a restaurant as Peterson had told investigators. Peterson stopped his vehicle, turned his car around and picked her up. At the house, she said, he paid her about $50 in exchange for oral sex.

The Peace Corps and State Department referred their findings to the Department of Justice. In a November 2019 letter to the Peace Corps Office of Inspector General, the agency said it had determined it couldn’t charge Peterson because the incident happened outside U.S. jurisdiction. The agency did not say whether it had weighed charging Peterson with lying to federal agents.

“It’s a shame we weren’t able to prosecute,” a State Department assistant regional security officer in Dar es Salaam wrote in an email in January 2020. “But at least he won’t be representing the [United States] in the future.”

Peterson's past included warnings about behavior

Throughout the investigative file, Peterson’s past federal employment comes up only briefly in a mention of his time working for the Peace Corps in Togo in the 1990s.

Nelson Cronyn, Peterson’s former boss in Tanzania, told a security official that when Peterson applied for the job, he reached out to a former Peace Corps official who knew Peterson from Togo. The woman, Marcy Kelley, told Cronyn that Peterson liked to drink, though she didn’t believe his alcohol consumption was still an issue.

Records show Peterson otherwise received positive recommendations — including from Kelley’s husband, James Bell, a former Togo country director for the Peace Corps.

Cronyn told the security official that he only received one report about Peterson in the two years they had worked together in Tanzania: A volunteer had seen Peterson at a bar with two younger women who were presumed to be prostitutes.

He said he confronted Peterson, who told him the women were relatives.

Cronyn, Kelley and Bell all declined to comment when contacted by USA TODAY.

The Peace Corps said its own records on Peterson’s prior employment are incomplete because it has destroyed most documents from that time. USA TODAY contacted other former Peace Corps volunteers and employees in an attempt to better understand Peterson’s history with the agency, which started when he was a 22-year-old volunteer.

Peterson grew up in Carroll, Iowa, a small city of about 8,000 people. His mother was a school teacher, his father a Presbyterian pastor who told the local paper he saw ministry as a way of “building up” after serving in the Army during World War II and witnessing the destruction caused by war.

Peterson, thin framed with a neat mop-top and wide-rimmed glasses, was a member of the drama department, concert band and student senate at Carroll High School. After graduating, he attended the University of Iowa and then followed in the footsteps of an older brother who had served with the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone.

Peterson arrived in Senegal, a former French colony in West Africa, in 1977. A former peer described him as a dedicated volunteer who embraced the Senegalese culture and learned both French and Wolof, a local language.

“When I went into the Peace Corps, I thought I went in as open-minded as possible, and with the idea that I would learn a lot. I still thought I could save the world. That’s a good motivational factor,” Peterson told his hometown paper in 1981. “But you soon realize that it’s not that easy. I feel that I learned much more than I ever taught anybody as a Peace Corps volunteer.”

Peterson stayed in the country after finishing his service, for a time working for USAID, and married a Senegalese woman. In the late 1980s he was cast in a minor role in a film by Ousmane Sembene, a famed Senegalese director often referred to as the father of African film. The movie, Camp de Thiaroye, depicted a 1944 massacre of West African soldiers who rebelled while detained by French troops. Peterson played an American soldier who was briefly held captive by the West African forces.

“I’m American, don’t you understand?” Peterson says in his main scene, as he thrashes around the barrack where he is being held. “What do you want with me? I’m from the USA!”

By the early 1990s, Peterson was working for the Peace Corps in Togo, federal records show.

Sheila Waterman, a physician assistant who spent 27 years working for the Peace Corps as a medical officer, met Peterson there. She told USA TODAY that several Togolese staff told her Peterson was bringing prostitutes to the Peace Corps office at night. Waterman said she asked questions but the employees didn’t share more.

“I tried to keep an eye on it,” Waterman said. “But it was evident that there was something going on which was disturbing the staff and they were not going to discuss it.”

Waterman said she sent an anonymous letter to a regional Peace Corps official, sharing what she had heard, but never knew what came of it. She said she also confronted Peterson, who denied the allegations.

USA TODAY spoke with a second former Peace Corps employee who worked with Peterson in Togo. The former employee asked to not be named but described being aware at the time that Peterson had a drinking problem and also hearing that he hired prostitutes.

Waterman and Peterson both eventually left Togo — she for medical school in North Dakota and Peterson for South Africa. Peterson had been selected to help open the agency’s first program in South Africa, a historic moment following the end of apartheid. After that post, Peterson worked in the private sector before rejoining the Peace Corps in Tanzania in 2017.

Martia Glass, a former Peace Corps regional medical officer who worked with Peterson in South Africa and knew Waterman through the agency’s medical community, told USA TODAY that she remembers Waterman warning her about Peterson and sharing concerns related to him and sexual misconduct. She said she kept an eye on Peterson but never personally saw any troubling behavior.

Waterman, who left the agency in 2008 and now lives in Australia, only recently learned of what happened in Tanzania. She said it prompted her to contact the Peace Corps Office of Inspector General and share her recollections from Togo. Earlier this year, USA TODAY reported that the watchdog was again looking into Peterson and whether he had a history of hiring sex workers overseas. A spokeswoman for the inspector general declined to comment.

Waterman said she contacted the office out of frustration that Peterson hasn’t been held accountable for his actions.

“I felt guilt that I hadn’t taken it further [in Togo] because I realized his behavior just had continued,” she said. “I also felt immense anger that he should be in such a powerful position and able to control and manipulate and continue to be so corrupt with people that we were working with the Peace Corps to help.”

During lengthy review, Peterson kept collecting paychecks

When the U.S. Department of Justice in November 2019 declined to charge Peterson, the agency sent the case back to the Peace Corps to handle administratively.

But Peterson would remain employed by the Peace Corps for 18 months after the incident — including a year after the agency’s Office of Safety and Security finished its investigation, records show.

During that investigation, the agency again interviewed Peterson. Five months after he told the agents at Dulles International Airport that he consumed enough alcohol to likely be over the U.S. legal limit to drive, Peterson sought to clarify his level of impairment and said he may have been “buzzed” on the morning of the incident, but not intoxicated, according to a summary of the interview. Peterson also said he did remember a body being loaded into the back of the police truck but that he didn’t know it was someone he had killed.

He hoped, he said, to keep his job.

The office of safety and security finished its review that month, records show. Seven months later, the agency notified Peterson that it planned to revoke his security clearance.

Peace Corps spokesman Troy Blackwell, in a statement, declined to explain the delay, saying only that the agency made its decision after reviewing the findings of its own and the inspector general’s investigation.

Peterson appealed the decision, records show, and roughly five months later a determination sided with the agency. Before his 30-day window to file a further appeal closed, Peterson resigned. In a 93-word letter to the agency that his attorney asked to be placed in Peterson’s security and personnel file, Peterson expressed his “sincere apologies” for his “unacceptable actions” in Tanzania.

“I know and understand that the ramifications of my actions have greatly affected many and I am deeply sorry for that,” he wrote. “I fully acknowledge and understand the seriousness of my actions and continuously seek forgiveness ever since I was medically evacuated from there over a year and one-half ago.”

Over 18 months of paid leave, Peterson’s salary, unused vacation time and bonuses added up to more than $258,000.

The people he hurt got far less.

Peterson’s victims each signed settlements with the Peace Corps, receiving payouts in exchange for agreeing to not make any legal claims against the agency or Peterson. The records make no mention of the victims having their own lawyers, and the Peace Corps has declined to say whether they did.

The sex worker received about $2,200. The first woman Peterson hit was paid roughly $6,500.

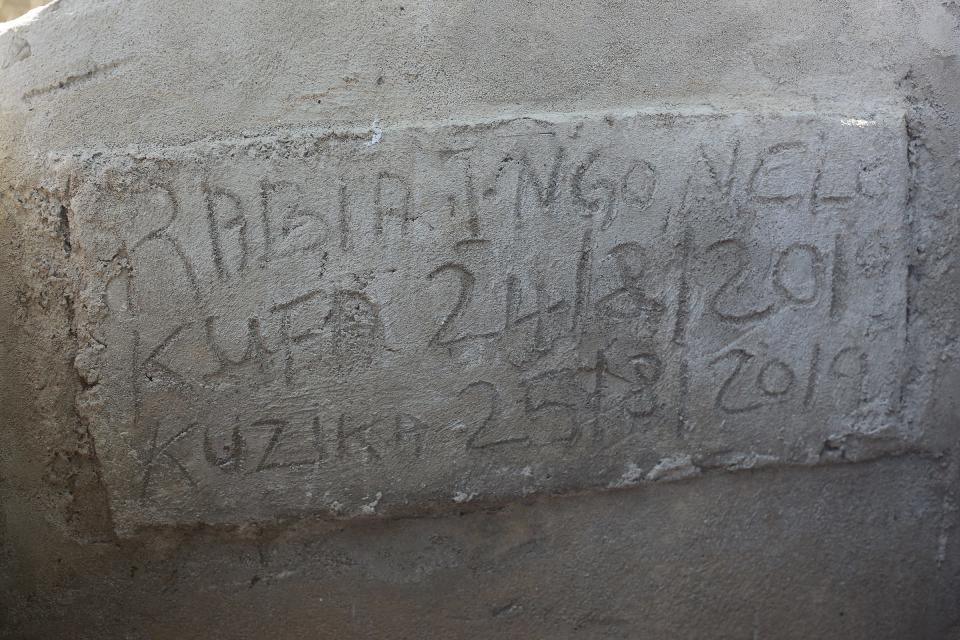

Issa, who supported her family selling fried cassava and doughnuts at her roadside stand, left behind three children, two of them minors. The family buried her in a cinderblock-walled cemetery and marked the grave with a simple concrete headstone. On Issa’s death certificate, the cause of death was summarized in a single word — unnatural.

The U.S. government’s compensation for her family’s loss: $13,000.

USA TODAY reporter Emily LeCoz contributed to this article.

Tricia L. Nadolny and Nick Penzenstadler are reporters for USA TODAY. Tricia can be reached at tnadolny@usatoday.com or on Twitter at @TriciaNadolny. Nick can be reached at npenz@usatoday.com or @npenzenstadler, or on Signal at 720-507-5273.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How feds blocked US citizen's arrest after he killed woman in Africa