They are recovering from drug addiction. Now, they're helping others in Rhode Island.

Addiction led Rhonda Warren and Paul Moore to years of despair, including doing time in prison.

Recovery set them free – and put them on the road to helping others with their hard-won wisdom.

Peer counseling is frequently part of the journey of addiction recovery. Studies show its benefits include reducing the length of hospital stays and symptoms of depression and anxiety for patients, along with boosting the self-confidence and skills of the counselors themselves.

At Providence-based Project Weber/RENEW, more than 60% of the staff has “lived experience” with addiction, the criminal justice system or being unhoused – and most of those have experienced all three, said executive director Colleen Daley Ndoye. Some of those working at the harm-reduction and recovery nonprofit have relapsed and overdosed multiple times, but their lives have been saved.

“Telling somebody what to do is really sort of useless if the person doesn't believe that it's even possible,” said Ndoye. “So rather than telling people what to do, our staff are just living examples of what to do … and that as long as you keep trying, change is possible. It is a living testimony.”

Elinore McCance-Katz, a Rhode Island psychiatrist who became the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' first assistant secretary for mental health and substance use in 2017, said peer support specialists help people with addiction disorders “stick with their treatment,” but also provide hope.

“They a lot of times are a linkage for us, to help to keep people engaged and offer hope to people, because they are in their recoveries and able to talk about what it was like for them,” said McCance-Katz. “And people who are trying to recover can often benefit from hearing of their experience and getting support from them.”

That can be healing for the helpers as well as those they help.

Rhonda Warren's story

Warren, of Pawtucket, remembers seeing people she used drugs with become happy and stable in recovery, and she wanted to have a similar life.

Warren’s parents divorced when she was a baby, her father was an alcoholic, and living with her mother was difficult.

“She had different boyfriends and abusive relationships, so we got to see all of that,” Warren said.

Warren eventually turned to drugs and became addicted. “Drinking and smoking weed led to the harder stuff, especially having a child at the age of 15,” she said.

She found herself homeless and spiraling, especially after losing custody of her daughter.

“I ran away from home. My daughter was already taken,” she said. “I ended up hanging out on the street, hanging in the bars and shoplifting.”

Soon after, she began selling the drugs she had become addicted to. “I really thought I was going to die in active addiction,” she said.

The first time police caught her selling drugs, they let her off with a warning. But the second time, an undercover police officer arrested her.

Warren compared her experience in prison to being unhoused: “It’s kind of like being on the street. You’re getting in trouble in jail. You get into fights in jail. You’re not getting the support you need. I never had a psych doctor in jail that would help me get on meds and get stable.”

More: RI's first overdose prevention site has a location. Here's what to know.

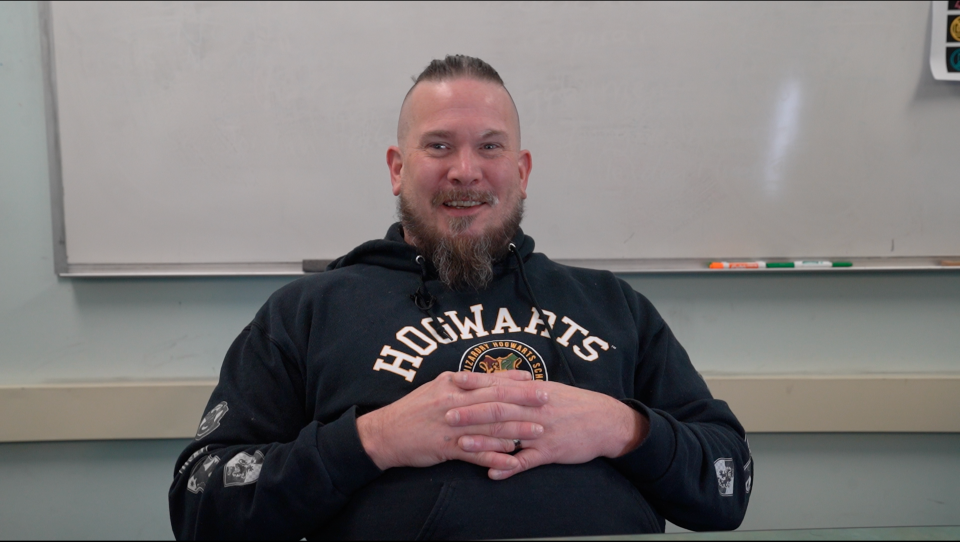

Paul Moore's story

Like Warren, Moore also suffered childhood trauma before he started using drugs and drinking at 14. That led to an addiction to prescription medication, which he resold to get other drugs, arrests for drug possession and time behind bars.

“I had been abused physically and emotionally by a teacher very young, and I don't remember for the next 40 years after that ever feeling comfortable in my own skin,” said Moore, who lives in Coventry.

Moore’s experience in prison hardened him more.

“There’s a dark cloud of impending doom always over your shoulder,” he said. “In just two short weeks of being in prison, I actually learned how to be more of a criminal than I was when I got in there."

Trauma, abuse, jail time often link those suffering from addiction

McCance-Katz has seen similar situations in her career. While the experiences are always a little different, she said, people with substance use disorders and severe mental illness often have abuse and traumatic experiences in their backgrounds.

”It's also possible that when someone is under the influence of substances, they become more vulnerable to traumatic experiences, because it's easier for others to take advantage of them,” she said.

'Game changer': Advocates praise new federal opioid treatment rules

As a peer counselor, Moore now understands how much the prison system can fail those with substance abuse and mental health issues.

“We got 5% of the world’s population and 25% of the world’s criminals. It’s an industry to make money, and it’s broken. It doesn’t work,” he said. “Other countries have looked at decriminalization and so on and are treating substance abuse as a wellness issue.”

McCance-Katz shared similar sentiments.

“The unfortunate case in our country is that jails and prisons have become the de facto mental institutions in our country,” she said. “It's my strong opinion … that we do not provide appropriate care and treatment for those with serious mental illnesses and severe substance use disorders. It is not a crime to have a mental illness.”

VICTA, an outpatient substance abuse and mental health treatment program in Providence, is onboarding its first group of peer support specialists, said chief operating officer Lisa Peterson. After decades working in community mental health and addiction, she knows well the many benefits of “peers,” as they’re known internally, as they have both the experience of addiction recovery but “the experience of being in the system,” she said.

From addiction to advocate: RI's mission to help pregnant mothers battling substance use

“It's really important to maintain those relationships with peers … because they'll tell us if our policies or procedures and ways of going about things are causing more harm,” said Peterson. “We're very receptive to that feedback, because there is often a pretty significant disconnect between senior leadership and service delivery.”

For Warren, Moore and countless others, peer counseling has shed light that has helped them move forward in their lives. And Warren has seen the impact she’s had on those she counsels.

“A lot of them know me from when I was out there on the streets. If they see me doing this thing, they get some hope that they can do this,” she said. “If I could help one person throughout the day, then I did my job.”

Sreehitha Gandluri is a high school senior and Youthcast Media Group (YMG) participant from Clarksburg, Maryland. She has been published in USA TODAY and the Washington Blade. Jayne O’Donnell is YMG’s founder and a former USA TODAY health policy reporter. YMG instructor Laura Ungar, an Associated Press medical/science writer, contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Peer recovery counseling helping RIers in addiction