Times Archive: Recovery response to USAir Flight 427 crash became a case study

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story is being reposted Sept. 8, 2022, to remember the 28th anniversary of the crash of USAir Flight 427.

In the moments after Flight 427 went down on a Hopewell Township hillside, the phones at the former Beaver County Emergency Services Center in Beaver burst with activity, and confusion soon reigned.

What kind of plane? How big of a plane? Which airline? Where did it crash? Some callers said they thought it went down in Green Garden Plaza. Others said it was in the soccer field near the plaza. One caller claimed the plane hit Aliquippa Community Hospital.

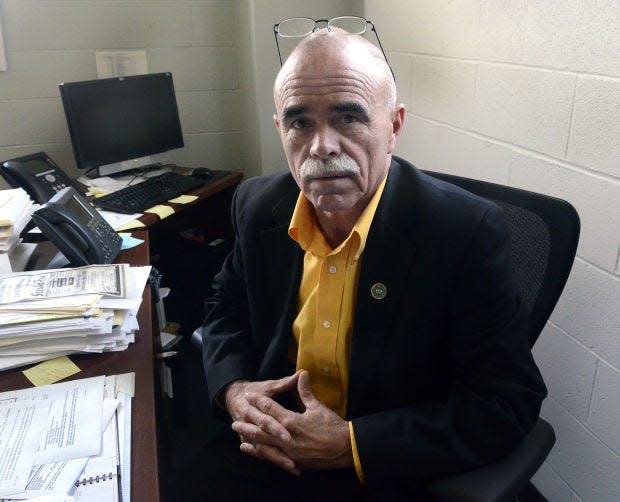

Wes Hill, 58, now the director but then the assistant director of emergency services under the late director Russ Chiodo, rushed to the crash site from a hazardous-materials training session at the Conway Yards. First-responders and others who saw the crash flocked to the scene, too.

Hill, like others who initially arrived at the site, quickly realized that all the police, paramedics and firefighters clogging the incoming roads were not going to be saving lives.

“The hardest thing,” he said, “is telling someone who's trained to do something they can’t do it.”

‘A TYPICAL NIGHT’

Randy Dawson, a senior dispatcher at the time and now the deputy director under Hill, recalled that there was a head-on collision on Green Garden Road at 4 p.m. that day, then at 6 p.m. was the yearly siren test for the Beaver Valley Nuclear Power Station.

“It was just a typical night and then that first call comes in saying you have a plane crash,” Dawson said. He said dispatchers handled about 250 calls in the 15 minutes after the crash.

The plane hit at 7:03 p.m., and a post-crash report by the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency said a Hopewell police log entry at 7:04 p.m. referred to a “hysterical caller” reporting that a commercial plane had crashed behind Green Garden Plaza.

Dawson fell back on his training to try to glean accurate information from callers. It would be 15 minutes after the first calls came in that county officials would call the Pittsburgh International Airport control tower with information on the crash because the airport had yet to contact them.

Once everyone knew where the crash site was, the airport activated its “Zulu” plan, which at the time applied only to a downed plane on airport grounds. In the meantime, the PEMA report said, a medical helicopter in the area landed near the site and dropped off personnel who ran to the scene.

PEMA concluded that 13 fire departments, 17 police units and four paramedic units were initially dispatched, but dozens more took it upon themselves to dash to the site, adding to the already confusing and chaotic situation.

“This overreaction by the emergency response community, although well-intentioned, complicated early efforts to organize and control the response,” PEMA reported.

Mitchell Unis, owner of the Unis car dealership in the plaza, offered his building as a command post. Cars were moved to accommodate vehicles, and “the parking lot was soon a sea of flashing lights,” the PEMA report said.

Download the PDF of the report

With a commercial crash such as Flight 427, it was also inevitable that the media would come. By midnight, the report said, there were 17 large TV news vehicles and more than 100 reporters in the same plaza area where responders were gathering.

SECURITY

Harry Flaskos, a commander with the Beaver County Sheriff’s Office, arrived and immediately set up a command post. Later, then-Sheriff Frank Policaro put Flaskos in charge of securing the site and keeping looters, curiosity-seekers and media away.

Flaskos, a 79-year-old Vanport Township resident and former Vanport police chief, said, “The name of the game was to preserve the area. Nobody comes in.” Hopewell officers, county deputies and state troopers established a perimeter around the site with the order to “use the force that is necessary” to keep trespassers away, he said.

A report by Flaskos two weeks after the crash said there were seven arrests made -- four people were turned over to Hopewell police while three were given to Raccoon Township police -- and two motorcycles were confiscated.

BIOHAZARD

While federal investigators arrived to probe the crash, the first task was to build an access road to the site. Allegheny County’s “Delta” team, an emergency response crew, came in to build a temporary road so equipment could be brought in.

The crash, it turned out, was the first one deemed a biohazard because of the scattered remains. In turn, the National Transportation Safety Board required federal investigators at the site to wear biohazard gear.

Then-Beaver County Coroner Wayne Tatalovich Sr. and deputy coroner/pathologist Dr. Jim Smith disagreed with the decision, arguing that funeral directors and coroners deal with body parts all the time.

For Hill, the county hazmat team leader at the time, the biohazard designation meant that the plane parts recovered had to be decontaminated before being taken to a hangar where officials were trying to piece the aircraft back together.

It was left to Hill to come up with a plan to decontaminate plane parts at the site without using too much water. That night he sketched a few plans until he settled on one that would become a model for other crash responses.

“Nobody had ever done it before,” Hill said.

Under the plan, a hole was dug near the site and tarp was laid down. Work benches were built on which plane parts were scrubbed with bleach and then rinsed off with spray bottles to keep water usage to a minimum.

Water and residue flowed down into the lined hole that also had absorbent pads at the bottom. Hill monitored how much water was in the hole and a vacuum truck siphoned the hole each night and hauled the water to the Hopewell water treatment plant.

Workers’ coveralls and gloves were tossed out at the end of each shift. Boots were kept only if they looked clean enough to reuse.

‘ON THE HILL’

The psychological and emotional stress associated with the recovery process overwhelmed many. One woman training to be an emergency dispatcher left the center that day and never came back.

It was worse for those workers at the site. “The stress of work on the hill and at the morgue soon made itself evident in the high attrition rate among young and inexperienced volunteers,” PEMA’s report determined.

As the “daily stress” took its toll and volunteers went back to their full-time jobs and lives, the recovery effort fell to experienced civilian and military teams. One of the recommendations that came from the PEMA report was that state-certified hazmat crews be trained in biohazard recovery, too.

Even grizzled military veterans were stunned at the carnage left by the crash, Hill said. A few responders to the crash came the first night and never returned.

For his part, Hill insisted that recovery workers get stress counseling from Red Cross personnel or clergy, who were on site. Some refused, he said, insisting they didn’t need to talk to anybody.

But, Hill said he would tell them to just grab some pizza or a cup of coffee, anything to get them to sit down with counselors.

“I had people who had issues with it for years afterward,” Hill said. “For years.”

This article originally appeared on Beaver County Times: Recovery response became a case study