Red Farmer's racing odyssey to the Hall

R ed Farmer’s drive to the NASCAR Hall of Fame started late one night in 1953. He was behind the wheel of a Hudson Hornet he planned to enter in a race on the beach track in Daytona. The car was too big to hook up to the tow bar he usually used, so he simply drove it from where he lived in Miami to Daytona Beach.

A veteran of small dirt tracks in southern Florida, Farmer was headed to his first NASCAR event. It was a passenger car he drove off the lot; the only modification was his addition of a roll cage. He and mechanic Wayne Kackley stuffed their luggage and toolbox in the trunk and drove north on old Highway 27.

Easy miles clicked under his tires along the empty highway as they neared Orlando. Farmer started to wonder how fast that Hornet was. Looking around, seeing only the open road, he decided it would be easy enough to find out.

He pushed his right foot down on the pedal. The speedometer turned like an over-eager clock hand … 70, 90, 100 miles an hour. Suddenly the road ahead made a 90-degree turn. “We were going about 50 miles an hour too fast to make that turn,” he says.

The road veered right.

The Hudson went straight.

I want to be like Ralph Moody. I want to be able to answer them boys, help them out as much as I can. I’ve tried to do that my whole life in racing.”

It hurtled across the oncoming lane and onto an old dirt road cut into an orange grove. He needed half a mile to slow it down without spinning into the trees. As he once put it: “We turned around, came back to the road again. I said, well, we know it will run fast.”

And he’s been running fast ever since in a career that has stretched into its 75th year and culminates with his induction Friday into the NASCAR Hall of Fame.

RELATED: Hall induction slated for Jan. 21 | Inductees of NASCAR Hall of Fame

SEEING IT ALL

All members of the NASCAR Hall of Fame made, participated in and witnessed history. Few, if any, did all three like Farmer, who was elected in 2020. His first race was in 1948. Now 89, he still races regularly at the Talladega Short Track across the street from Talladega Superspeedway.

In those 75 years, he won 752 races and four national NASCAR championships. When NASCAR announced its top 50 drivers in 1998, Farmer made the list. He studied the names. He had raced against all but one of them — Red Byron.

He raced against the patriarchs of NASCAR’s greatest families — Lee Petty and Ralph Earnhardt — and against the driver most responsible for modern NASCAR, Jeff Gordon. In 1956, he turned 24 and raced against a team owner born in 1898. In 2021, he turned 89 and competed against drivers born in the 2000s.

But it’s not just the breadth of years. It’s the depth he filled them with. He saw tragedy and triumph, victory and failure. His life has been full of both laughter and tears. When Farmer steps to center stage to give his induction speech, expect pure racing gold. “They’re going to have to give me about half an hour,” he says. “I told them, hey, I’ve got 75 years of bullshit I’ve got to tell. I can’t get up there and do it in five or six minutes. I’ve got too many people to thank. I’ve got too many great stories to tell.”

He is a Korean War veteran. He was married to Joan for 65 years; she died in 2015. They had three kids. Two years ago, he married Judy Goodwin, the widow of an old racing buddy. Together they have dozens of grandchildren, great-grandchildren and even one great-great-grandchild.

One of Farmer’s best friends is Tony Stewart, a fellow Hall of Famer and racing legend whose life has also been filled with laughter and tears. The two hunt and fish together, and Stewart will introduce him at the Hall of Fame ceremony.

“When you think of how many decades that Red’s been racing, it’s amazing,” Stewart says. “He’s raced more years than a lot of people live. To work on his cars and race as hard as he does is really a testament to his love of the sport. A — I just hope to live that long, and B — I hope I’m healthy at that age. If I can have his health and personality at that age, then I think that would be a successful life.”

A twinkling-eyed raconteur, Farmer wears an impish grin that answers the question of why he keeps racing even at 89: Because it’s damn fun! If something gave you what racing has given Farmer, you’d keep doing it, too. As he nears his 10th decade, he will keep turning fast laps as long as he’s still standing, as he puts it, on the green side of the grass.

Enter Parallax Text

RISE OF THE ALABAMA GANG

Farmer started racing in 1948 in an event at an abandoned Air Force base where he says the straightaways were parallel runways. He rolled the car, but it landed on its wheels, and he kept going. He was hooked.

In the mid-1950s, Farmer worked as an electrician during the day and drove a Ford at tracks across South Florida. He admired the Chevy V8 engines and bought one. He and his mechanic discovered it was missing the plate to hold the cam shaft in. For help fixing the problem, he recruited a teen-ager in the area who Farmer thought knew all about Chevy engines.

That teen-ager now says he didn’t actually know much about Chevy engines, but he wasn’t going to tell Farmer, his hero, that. With the teen’s help, Farmer produced a car that ran second in the first race and then racked up nine feature wins in a row. Says Farmer: “That kid that helped us build that engine was a boy named Bobby Allison.”

In the late 1950s, the building industry slowed. Farmer was supporting three kids, his wife and his wife’s grandmother on weekly unemployment checks of $33, according to author Clyde Bolton in his book, The Alabama Gang. “The only other thing I had was a race car,” Farmer says in Bolton’s book.

Bobby Allison — a 2011 NASCAR Hall of Fame inductee who won 84 Cup races — moved from South Florida to Hueytown, Alabama, in 1959 and persuaded Farmer to join him. From there, Bobby Allison, brother Donnie Allison and Farmer barnstormed to races in two pickups and a station wagon. According to Donnie, in 1962, they entered 106 races and won 96 of them.

RELATED: Alabama Gang through the years

When they arrived for one race, Jack Ingram — a 2014 NASCAR Hall of Famer who won 317 NASCAR-sanctioned events — saw them and said, “oh, no, here comes that damn Alabama Gang again,” a reporter overheard it, and that moniker stuck.

“We were real competitors against each other. But we were also best friends off the racetrack,” Farmer once said. “When they dropped the green flag, it was best man wins. There was no friendship there until the race was over. Then we were back to friends again.”

The Alabama Gang grew to include Jimmy Means, Hut Stricklin, Neil Bonnett and Bobby Allison’s sons, Clifford and Davey.

Decades later, the depth of the friendships between members of the Alabama Gang remains evident in the good-natured jabs they hurl at each other. “The only way you can tell Red is lying is his lips are moving,” Bobby says on a video called Stock Car Legends Reunion, at which Farmer told the stories of driving to Daytona and meeting Bobby.

RELATED: Talladega’s ties run deep with Alabama Gang

When Bobby arrives for the taping, Farmer cracks: “I knew Bobby would be the last one here. When he dies, they’re going to have to hold up the funeral for 30 minutes for him to get there.” Donnie greets Farmer by asking, “Did they get you out of the nursing home?” and that was more than 20 years ago. (Donnie is now 82 to Farmer’s 89.)

Tragedy redefined those friendships. Bobby Allison nearly died in a career-ending wreck in 1988 at Pocono. Clifford Allison died in a crash during an Xfinity Series practice in 1992 at Michigan. Bonnett died after hitting the wall head-on in 1994 at Daytona. When Davey Allison crashed his helicopter and died in 1993 at Talladega, Farmer was his passenger.

Those deaths haunt him; he has carried survivor’s guilt for decades. “Maybe I cheated some of them. I’ve got nine lives. I think I’ve used up eight of them. I’ve got so many great friends of mine that aren’t with us anymore,” he says. “Some of them were snuffed out in the prime of their life, like Davey. It’s a hard deal. So many close friends I’ve lost over the years. But they passed away doing what they loved to do, and I understand that.”

His relationship with Davey Allison was particularly strong. It was part friendship, part father-son, part driver-crew chief (roles they played for each other in the Xfinity Series) and total hell-raising, says Liz Allison, Davey’s widow.

“Davey really leaned on Red for the humor in his life, but also just that camaraderie, that steadfast friend,” Liz Allison says. “They were always laughing and goofing, a lot of times to annoy the crap out of me. I’m chasing two little kids around the track, and they’re just hee-haw laughing and getting in trouble. That was the essence of their friendship. They loved each other and were always in trouble together.”

RELATED: The days of Davey | Davey Allison through the years

They spent time together nearly every day, often at the race shop in Hueytown. “As much of a goofball and a troublemaker — in the most loving way that I can say that — that Red always has been, he has a really big heart,” Liz Allison said. “And he truly never got over Davey’s death.”

A LIFETIME OF STORIES

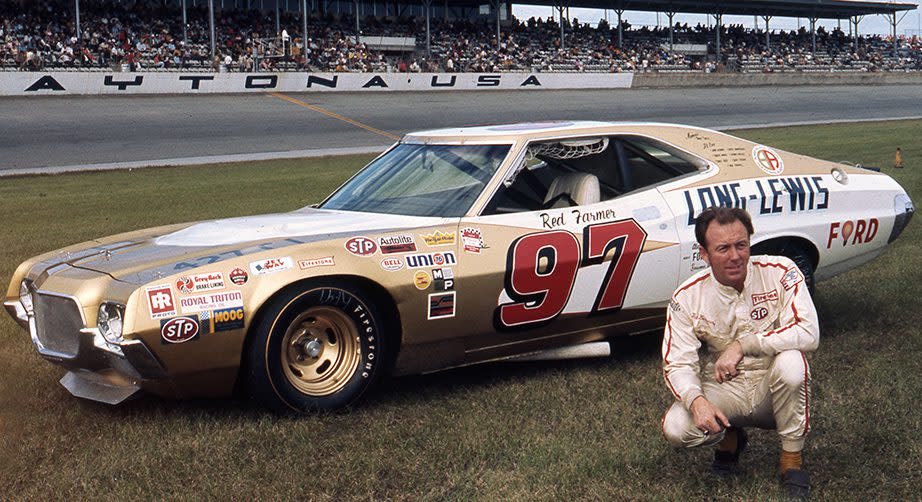

Long-Lewis Ford (an Alabama dealership) has been Farmer’s sponsor since 1962. Six decades after it began, the agreement rests solely on a handshake. It has never been written down, vetted by lawyers or made formal in any way.

Farmer and former owner Vaughn Burrell trusted each other. A scribbled name on a piece of paper with a bunch of rules pecked out by lawyers would add nothing to that and might even diminish it. A man’s word is sufficient, he says. “That’s the way you should be able to do business,” Farmer says. Burrell will present Farmer his ring at the induction ceremony.

Farmer entered 36 races in NASCAR’s Cup series, his first in 1953 and last in 1975. He had zero wins, two top fives and three top 10s. Nobody doubted he had the talent to succeed at NASCAR’s premier division, but top rides were scarce in those days. He figured he could make more money winning at local short tracks than he would riding around in the back at the Cup level.

Plus he would have more fun. A lifetime of stories (and hundreds of wins) at small tracks easily tops mediocre finishes at big ones.

His wife brought sandwiches for everybody, his kids sat in the grandstands, his good friends worked on his cars and his best friends, Bobby and Donnie Allison, were his competitors. The names and details have changed — his kids have grown (he races against his grandkids now) and the Allisons stopped racing decades ago — but his sense of being a member of a tight-knit community remains. “That’s something money can’t buy … The whole race track and everybody around is a big family,” he says. “I just enjoy being around people.”

All those years driving to and from tracks gave Farmer plenty of time to think. He is a fast-driving philosopher, Socrates of short tracks, Aristotle of asphalt. As he once told longtime NASCAR writer Jerry Bonkowski: “I’ve got a saying that I came up with: ‘How old would you be if you didn’t know how old you was?’ Seriously, if you didn’t have a birth certificate and didn’t know old you was, how old would you be? In other words, it’s a state of mind and how you feel about yourself.”

He feels pretty good most days. Ken Schrader — a former Cup driver who entered his first race in 1971, who still races on local dirt tracks, and who after 51 years as a racer trails Farmer by more than 20 years — spent time with Farmer at a track in 2021. “He looked like he was hiding 20 years,” he says.

Told this, Farmer laughs. “Sometimes I feel like I’m 50 or 60 years old,” Farmer says. “Sometimes I feel like I’m 95. It depends on the morning.”

Enter Parallax Text

While he no longer contends for wins, Farmer finishes regularly in the top 10 at Talladega Short Track. He led the points early last season before skipping races. He says he’ll know when he’s no longer competitive, and that’s when he’ll stop. As he often says, “I’m going to wear out, not rust out.”

He hasn’t worn out yet, but it’s not from a lack of trying. In The Alabama Gang, Bolton catalogued Farmer’s racing injuries: “broken right ankle, broken right foot, left leg broken on three occasions, left kneecap removed, two vertebrae in back broken, six ribs broken, cheekbone broken with subsequent loss of feeling in left side of face, burns on 40 percent of body, sufficient loss of hearing due to exhaust noise to necessitate a hearing aid.”

That list was compiled 50 years ago. “Since then,” Farmer says. “I’ve had my left shoulder replaced, my right shoulder replaced, my left knee replaced. And I’ve got screws and rods in my back to hold my spine straight. When it wears out, I just replace it.”

He wrestles with what he calls the “Itis Brothers” — arthritis, tendinitis and bursitis. He lost parts of fingers on one of his hands, which leads to a sight-gag joke. He says he holds his fingers out the window to make drivers behind him think there are two laps to go before restarts. As he tells it, he speeds off one lap later, and the drivers behind him feel snookered. He unfurls those fingers — they are half the length they are supposed to be, so they really add up to one. It’s not his fault drivers don’t understand fractions.

A series of recent health issues — he was hospitalized for heart surgery and nearly died of COVID-19 — have forced him to miss races. On top of that, his house, race car and the trailer he uses to haul it were damaged in a tornado last year.

And yet he keeps walking out to his garage every day at 8 a.m. to work on his cars.

I‘ve got too many people to thank. I’ve got too many great stories to tell.

He still hauls them to as many races as he can.

And he still carries with him lessons he learned at his very first NASCAR race nearly 60 years ago.

‘I WANT TO BE LIKE RALPH MOODY’

After the harrowing drive there, Farmer and his mechanic parked on the beach. He crawled into the back seat and sprawled out there to sleep. At some point, he rolled over and his hand dropped down toward the floorboard … and into water. Overnight, the tide came in. The car was sitting in the ocean.

They quickly moved the Hornet to higher ground and dried it out. As race time approached, Farmer realized he was out of his league. “I didn’t know what to do or how to do it. I was lost. I was like a short dog in tall weeds,” he says.

He walked around asking other racers for help. Nobody would give him any, except Ralph Moody, who would go on to become a successful team owner. It wasn’t just the quality of the help Moody gave him — he correctly predicted Farmer’s wheels would not withstand the pressure of the race — it was the kindness Moody showed in giving it. That conversation shaped the rest of Farmer’s life.

“I said to myself right then and here: I’m a nobody. I might always be a nobody. But if I ever win some races and become somebody, and a nobody comes up to me and asks me a question, I want to be like Ralph Moody. I want to be able to answer them boys, help them out as much as I can. I’ve tried to do that my whole life in racing.”