Reds' food rescue: What happens to all the hot dogs that fans don't eat?

Great American Ball Park filled close to 60% of it seats in mid-June as the newly-hot Cincinnati Reds bested the Colorado Rockies in three weekday matches.

But the big crowds didn’t quite clean out concessions. In fact, based on averages, they left about 730 pounds of perishable food behind over the series.

Until 2021, much of that was wasted.

Now, it goes directly from the stadium to hungry Cincinnatians.

It’s a success story Last Mile Food Rescue hopes to replicate across the city, as it tries to convince other stadiums to follow the Reds’ lead on food donations.

“They don't know how easy it can be," said Erik Hyden, who manages Last Mile’s donor solicitations.

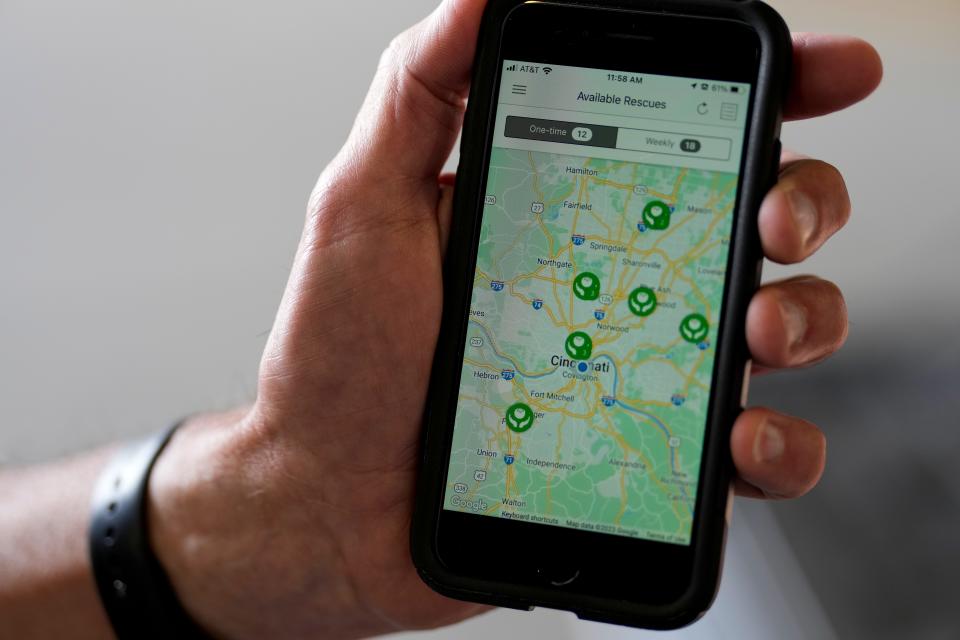

800 'heroes' make Last Mile runs

Mark Lawrence learned about Last Mile from a TV feature and thought, “Hey, I’m retired. I’ve got a truck.”

So early this year, the former utilities manager signed on as a Last Mile “hero” – one of 800-plus volunteers who pick up and drop off donated food.

At the end of the Reds-Rockies homestand, Lawrence pulled his black pickup into Dock 3 under the Reds' stadium a little before lunchtime.

Minutes later, he pulled away, his truck bed loaded with unsold but still edible leftovers from Delaware North, the stadium’s long-time concessions operator. No hot dogs and beer. But plenty of lettuce, mushrooms, peppers, celery and onions, along with bags of popped and packaged popcorn.

And a few minutes after that, he left the load in an Avondale parking lot, where a crowd soon began filling their bags with the produce and popcorn, plus frozen ground beef, bagels and even bouquets of flowers from other donors.

Shaunte Miller of Bond Hill was in the Avondale line, picking up food for herself and three elderly neighbors. They’d come for the fresh produce themselves, she said, if they weren’t using walkers or wheelchairs, Miller said.

When she first delivered Last Mile bags, she said, “They couldn’t believe the food. It’s so different than a (food) pantry.”

Avondale volunteer Jennifer Foster said she hears that all the time. “People are so shocked they can get the good quality food they can,” she said. “We load them up and make them happy.”

Once happy, they sometimes reach out for other help – where to find housing or clothes, where to look for a job.

Foster stations herself at the front of the food line to greet each person and answer the questions she can. “I’m the resource hub,” she said.

5.7 million pounds of food diverted from landfills

Julie Shifman and Tom Fernandez started rescuing food from restaurants, hotels, food stores and food distributors in November 2020, about a year after creating Last Mile Food Rescue.

They’ve since collected about 5.7 million pounds of perishable food – keeping it out of landfills and getting it to people in need.

TQL Stadium, home of FC Cincinnati, signed on early. The concessions team there has donated more than 20,000 pounds of food in three years. The University of Cincinnati just joined, with its concessions operator donating food from a dining hall in July and agreeing to turn over extras from Nippert Stadium this fall.

Delaware North, which has been feeding Reds’ fans since 1936, has been donating since the beginning. Leftovers from Great American Ball Park, at 32,000 pounds, have provided about 24,000 meals.

“For us, it’s a no-brainer,” said Ari Rubin, a Delaware North assistant manager, noting that six kitchens, 50-plus suites and 90-plus concession locations throughout the ballpark produce a lot of uneaten food.

“We know the extras will be going to the community,” added Gary Davis, the concessionaire’s executive chef.

Paycor Stadium, home of the Cincinnati Bengals, is not participating – yet. "We’d certainly love to have them join our other stadium partners," Last Mile Marketing Manager Beth Voorhees said. Representatives of Aramark, which handles concessions at Paycor Stadium, did not return a voicemail and two emails.

Part of solicitation manager Hyden's job: Convincing stadiums “there’s a safe, reliable solution” to their food waste. “We can place all kinds of food.”

Reds, FC enjoy Last Mile 'bump'

On the day that “hero” driver Mark Lawrence rescued food from the Reds' stadium, he’d already picked up 25 trays of prepared food from Downtown's Duke Energy Convention Center and delivered them to Shelterhouse, a facility for homeless men in Queensgate.

He was happy to grab two jobs off the Last Mile app and zip over from his nearby Covedale home for the runs. “I didn't know there was that big of a need,” he said.

Hyden did not know much about food rescue, either, despite a 25-year career as a Cincinnati restaurant chef.

When he stepped out of that business and found a new career with Last Mile last year, he quickly learned about local food insecurity.

Thanks to his restaurant years, he can now easily identify food sources. One example: He knows restaurants with Thanksgiving and Christmas menus will have leftovers. His challenge is to find recipients ready for delivery.

As longtime donors, TQL and Great American Ball Park concession operators don’t need any coaching on how Last Mile works. Now, their home teams, both enjoying winning seasons, are being rewarded for their loyalty, Hyden joked. “They all got the Last Mile bump.”

How to join the food rescue movement

Last Mile Food Rescue explains how to volunteer, donate food or request food donations on its "You Can Help" page.

Hamilton County R3Source's "Wasted Food Stops With Us" site includes ideas on where to donate perishables.

The Greater Cincinnati Regional Food Policy Council's site offers information about the local food ecosystem.

The Green Umbrella Regional Sustainability Alliance site explains food waste and how to reduce it.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: What happens to food fans don't buy at Reds' games?