How refugees are revitalizing American cities: A journalist's immersive book

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

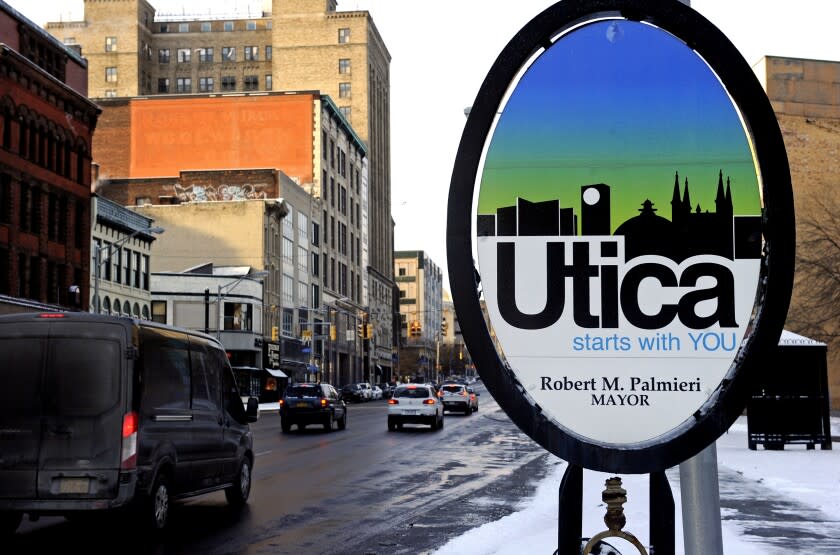

In the mid-19th century, Utica, N.Y., was home to more people than Detroit, Cleveland and even Chicago. Those cities soon outpaced this remote industrial town, but it continued growing, reaching 100,000 people in 1930 before plateauing for four decades. Then the inexorable decline that began across the Rust Belt took hold and Utica grew smaller and poorer. But there’s a twist: After bottoming out in 2000 at 60,000 people, Utica turned a corner and it began growing again, revitalizing its downtown, thanks in large part to refugees.

Many of the people who helped foster this rebirth arrived in Utica after experiencing hell on Earth in their war-torn homelands, be it Vietnam, Burma, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Somalia or Iraq. In her new book, “City of Refugees: The Story of Three Newcomers Who Breathed Life Into a Dying American Town,” Susan Hartman illuminates the humanity of these outsiders while demonstrating the crucial role immigrants play in the economy — and the soul — of the nation.

“Most Americans haven’t had contact personally with refugees,” Hartman noted in a recent video interview. “They feel worried and see them as people who will be a drain on the economy, with huge families on public assistance. I hope this book dispels the myths and puts a human face on the refugees, showing the reality of how hard they work.”

Hartman began exploring Utica and its refugees in 2013, publishing a story on the topic the following year for the New York Times. In the course of her reporting, she came to know the subjects of what would become her book: Sadia, a rebellious teenage girl in a Somali Bantu family of 12 headed by a single mother; Ali, an Iraqi who had worked for the U.S. during the war; and Merisha, who had fled Bosnia in the 1990s.

“This was very much an accidental book,” Hartman says. “These three people just hooked me. I was riveted by their stories and had no idea what was going to happen. I was always waiting for the next trip.”

Hartman kept going back for an additional seven years, learning the most intimate details about three families while putting their challenges and accomplishments in the context of the way Utica — along with cities like Buffalo, N.Y.; Dayton, Ohio; and Detroit — was regaining its footing thanks to newcomers from a wide array of countries.

“I’m a miniaturist and love the details of people’s lives,” she says. “I started with a story, not an agenda. I didn’t feel a need to make big statements. I felt it would be there if someone wanted to discover.”

Still, politics wormed its way into the book when Donald Trump became president by pushing a xenophobic agenda — and not only continued to attack immigrants relentlessly but also slashed the United States’ refugee program.

“It might make the book feel more political, because you become aware the city was on an upswing and beginning to thrive because of the refugees, but when the pipeline was cut, the city suffered,” Hartman says, noting that President Biden has reversed Trump’s attitudes and policies. (Biden has, however, received criticism from refugee advocates for his half-measures regarding people fleeing the war in Ukraine: He initially promised to welcome 100,000 refugees but then switched to the more precarious offer of “humanitarian parole.”)

“They are excited in Utica about welcoming more refugees,” Hartman says. “The companies and factories and the resort need them, and there is a hospital going up too.”

For all the uncertainty of the last few years, the political debate rarely touched the refugees themselves. “They are not as upset as you might think; they are focused on work and surviving,” Hartman says. “The refugees who were already here felt secure; they were Americans or on their way to becoming Americans and didn’t feel personally threatened. And the older people were not getting news from American sources but were focused on getting news from their home country.”

It’s also worth pointing out that “replacement” conspiracy theories notwithstanding, the refugees were hardly politically monolithic. Ali voted for Trump in 2016, though he did not reveal his choice in the last election. He liked the Republican’s economic policy and chose to compartmentalize his more xenophobic rhetoric. “If you come from an authoritarian country you’re used to Saddam Hussein,” Hartman says; by comparison, Trump never seemed particularly dangerous to Ali.

Hartman’s immersive reporting over eight years allows for such nuance to come through as the families carry on with their lives. Ali falls in love with an American woman named Heidi, but even as they begin creating a life together and save money to buy a home, he misses his native country and is eager to help it rebuild, returning to Iraq to work again for the American government.

Sadia, meanwhile, gets kicked out of her mother’s house for displaying an independent streak that feels too American to the family. Readers may be aghast at her mother’s cold-hearted behavior, but Sadia, despite her loneliness and struggles, manages to carve her own path. Hartman tries to put the family’s reaction in “a cultural context.”

“They saw Sadia as impossibly disrespectful, and her mother felt that she’d come back,” Hartman says, adding that she felt sympathy for the mother, whose 11 children led her to parent with a “triage” approach.

Merisha and her husband work hard and raise a family, but her ambitions lead her to start cooking and selling Bosnian food, prompting the family to pitch in and put everything on the line for her to open a restaurant — which launches in 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was taking hold. “Opening a restaurant is such a gamble, and when I went there, Merisha was absolutely exhausted and couldn’t even think about the pandemic,” Hartman says.

The family adapted on the fly, with the children finding other jobs to help pay the bills, while everyone scrambled to create a “to-go” restaurant during the shutdown. “They didn’t mourn,” Hartman says, adding that the restaurant survived and is thriving. So is Ali and so is Sadia, who has a baby, a husband and supportive in-laws, along with plans for her future.

No matter their journeys, success is a matter of perspective, one thing these newcomers all have in abundance. “When just about anything happens,” Hartman says, “these refugees can say, ‘I’ve been through worse.’ Their resilience is enormous.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.