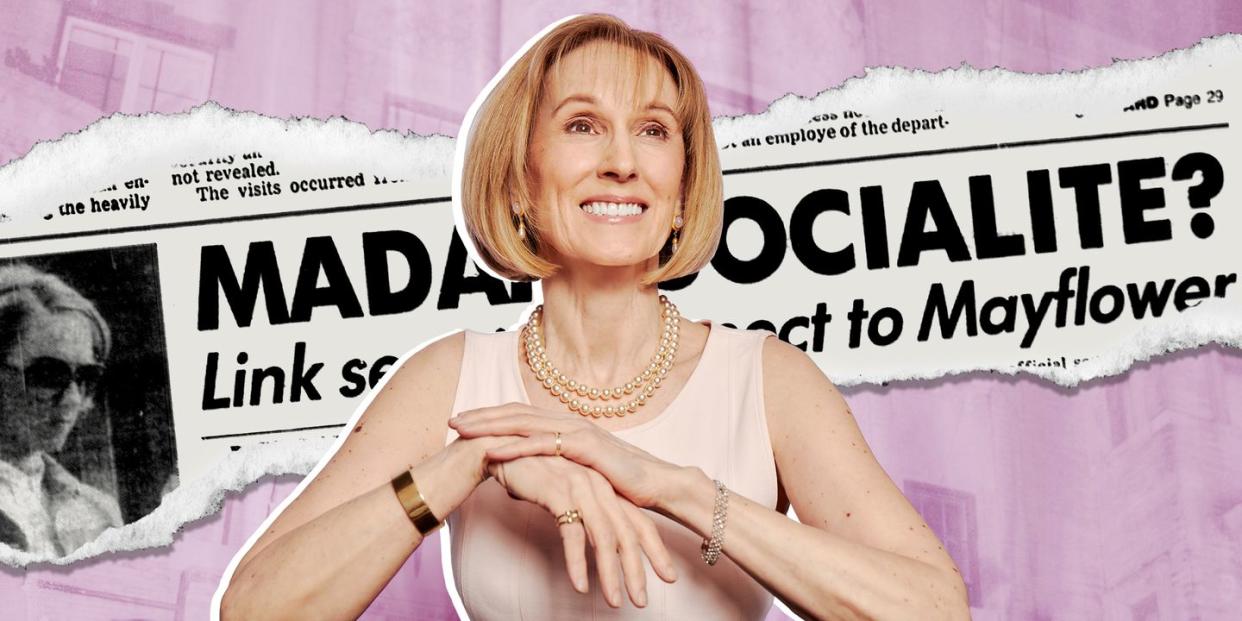

The Reinvention of Sydney Biddle Barrows: The Mayflower Madame Has Some Advice for You

Sydney Biddle Barrows is sitting in an Italian restaurant on the Upper West Side on a blustery February evening, weighing in on the topic that for the last 24 hours has consumed nearly everyone with access to a television or Twitter account: Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga’s performance at the Oscars the previous evening.

Witnessed by millions, including Irina Shayk, Cooper’s partner and mother of their child, who was sitting in the front row, the intimate performance launched a thousand “Are they or aren’t they” takes. “I wouldn’t have liked it,” Barrows says with a cocked eyebrow. “It’s one thing to see it in a film; it’s another to have all that passion playing out directly in front of you.”

Barrows has some experience when it comes to powerful men and their displays of passion. In the early 1980s she was arrested for running an escort service that catered to Manhattan’s elite. Discretion was the secret to her success; even after her arrest she refused to name names. “My attitude was, discretion was one of the main things that they paid for.”

This decades-old entry on her résumé could hardly be more at odds with the refined blond woman in her late sixties who approaches both meal and conversation with a controlled manner that speaks of a bygone era.

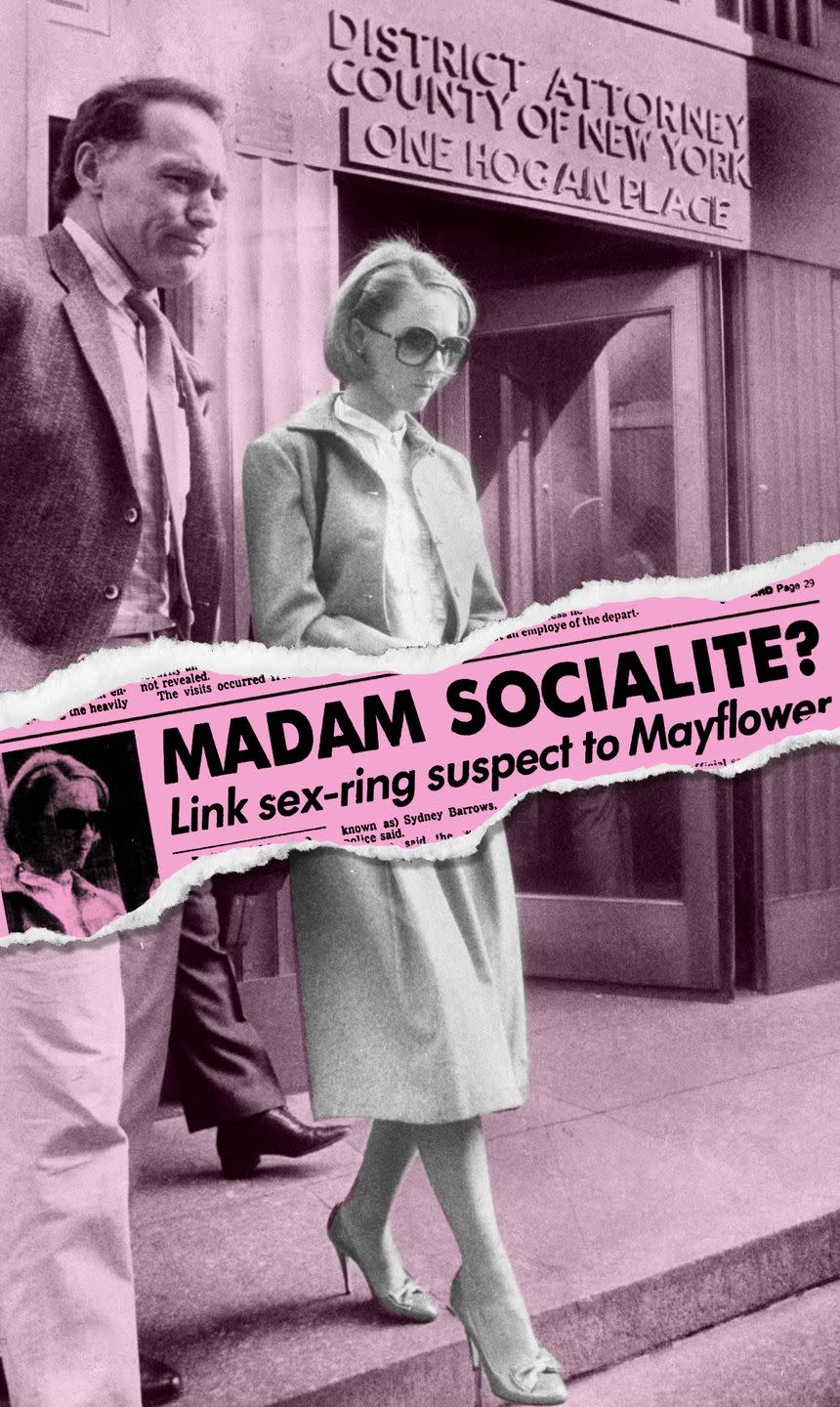

“I had to learn to use finger bowls to dine at my grandparents’ house,” she says, dabbing her mouth with a cloth napkin. It was this disconnect between her occupation and her upbringing that the tabloids latched onto in the aftermath of her arrest, promptly dubbing her the Mayflower Madam and launching her into a weeks-long inferno of coverage. George Rush Jr., who along with his wife Joanna Molloy penned a gossip column in the Daily News, says, “It was tabloid catnip.”

Thirty-four years later Barrows-now self-employed as a marketing consultant-is sanguine about her experience with infamy. “I lucked out,” she says, revealing a Kardashian level of media savvy. “The New York Post and the Daily News were having a circulation war. The Post had multiple editions a day, and all they would do is change the picture or the headline and people would buy all the papers.”

We now live in a world in which Esther Perel’s TED talk “Rethinking Infidelity” racked up 7 million YouTube views, making someone who preaches forgiveness a star, but 30 years ago that wasn’t the case. In the class-conscious Manhattan of the early ’80s, the shock that a “well-bred” woman might involve herself in such work-and enjoy it-was mind-boggling.

“I think it brought out the thin differences between prostitution of the literal kind…and the sort of roles that women play, even in high society,” Rush says, referencing the trope of an older, wealthy man with a so-called trophy wife.

And yet, from a post–Lean In vantage point, it’s easier to see Barrows as a talented businesswoman with limited avenues open to her (her father refused to pay for her education, telling her, “Some rich man will marry you. Why should I send you to college?”) who made the most of her opportunities. “I did what made sense,” she insists.

Indeed, what stands out most in retelling Barrows’s story in 2019 is how much it smacks of agency and how neatly it would fit into Silicon Valley’s startup narrative. The thumbnail version goes like this: A few years after leaving a two-year program at FIT, Barrows found herself unemployed. She took a job answering phones at an escort service, spotted an untapped market, and concluded that she could do better running a service herself.

The business “was all run by men with, excuse my language, low foreheads and big nuts,” she says. “There were people who called who I could tell were not the kind of people who were looking for ‘hot babes.’”

What they wanted, she believed, was “someone who was a genuinely nice person.” And that’s what she gave them. “I was really good at creating an experience.”

Barrows still refers to the women who worked for her as “my girls,” and for years she kept in touch with a number of them. Whenever she mentions them, she is quick to make clear that they worked for her by choice, indignant at the suggestion that it might have been otherwise.

The idea that women could be participating in sex work voluntarily was an impossible one at the time. But for Barrows this was always the case with the women she employed-a stark difference from women who are coerced into the business. “For most of my girls, it was fun,” she says.

And the men? According to Barrows they wanted companionship as much as or more than sex. “I had people call up to have somebody come over to watch the Super Bowl with them,” she says. “I had clients who would call the office and chat with the phone girls, just to have a connection.”

Following her 1984 arrest, Barrows cut a deal with prosecutors, pleading guilty to a misdemeanor charge of promoting prostitution. She was fined $5,000 but received no prison term, and then she spent the next decade being followed into restaurant ladies rooms by women curious to know what exactly the women who had worked for her were doing.

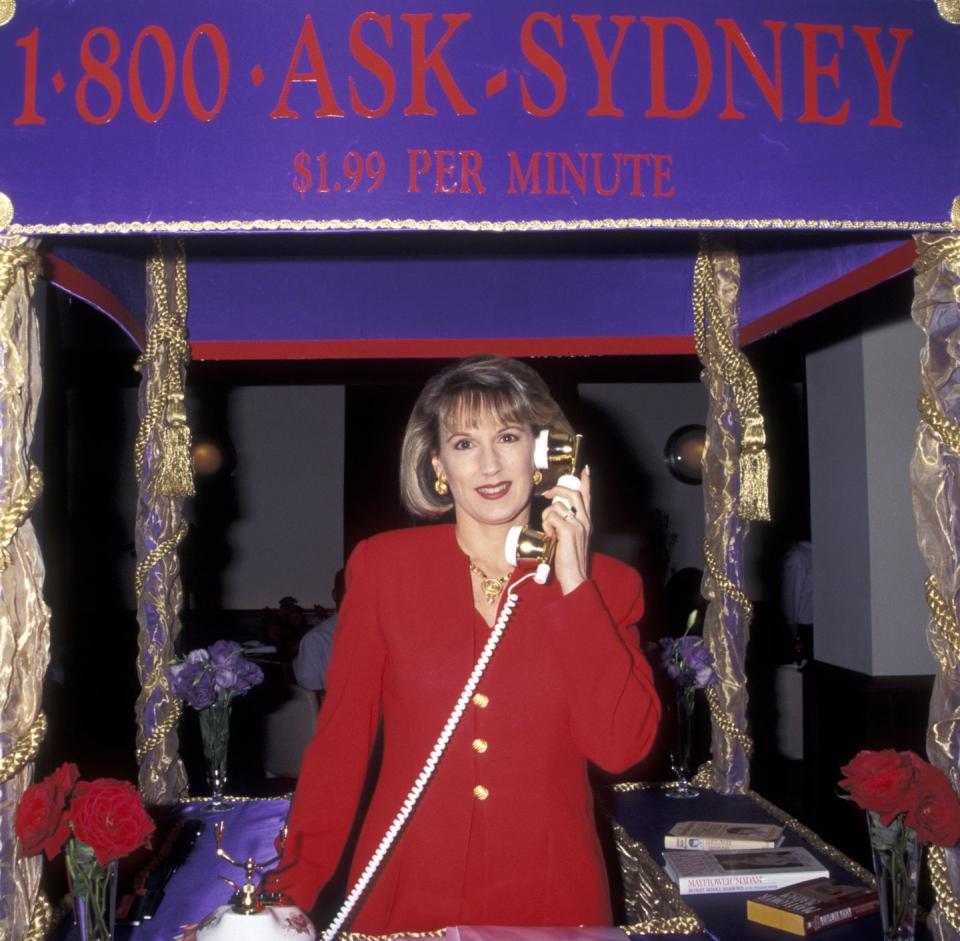

This happened so often that she wrote a book, Just Between Us Girls: Secrets About Men from the Mayflower Madam, which was also a bid to help pay the bills.

It turned out that the compelling thing the girls were doing was paying attention. “What I learned was that the men who were married strayed to stay,” Barrows says. “They didn’t want to leave their wives and their families and the life that they had. People mostly just want to be seen.”

And while she’s sympathetic to Jeff Bezos’s situation in theory, she thinks the way he behaved was “inexcusable.” “Sending pictures? Seriously?” She believes today’s high-profile men make a mistake by turning to “amateurs.” “Working girls have a code of honor,” she says. (Yes, we know prostitution is still illegal.) “When was the last time you heard of a call girl blowing somebody’s cover?”

Barrows still lives in the one-bedroom apartment she occupied when the police arrested her at home in October 1984 (“When you have a rent-controlled one-bedroom in New York, they take you out in a box,” she says), and she still eats breakfast at the diner on the corner. She is currently single; she notes that for many years her dating life suffered.

These days she wonders if there might be a new audience for her story. Her 1986 book, The Mayflower Madam: The Secret Life of Sydney Biddle Barrows, was adapted into a TV movie, but Barrows isn’t sure who holds the option on the book now. She says she’ll have her lawyers look into it.

A retelling of the tale would no doubt reject the punchline narrative that has dogged Barrows all these years and instead thrust her practical views about marriage and fidelity into the modern conversation.

“I was always one of those people who thought if you cheated on me it means you don’t love me anymore,” she says. “After my business I really changed my tune. My attitude was, ‘You know what? If you’re going to cheat on me you just have to be respectful about it. You can’t do it with my best friend or with someone I know. As long as I don’t find out about it and my friends don’t know about it and you don’t give me some disease, you go do what you want.’”

This story appears in the May 2019 issue of Town & Country. Subscribe Now

('You Might Also Like',)