'If they need me, I will rejoin': Taliban prisoners freed by Kabul stand ready to rejoin the fight

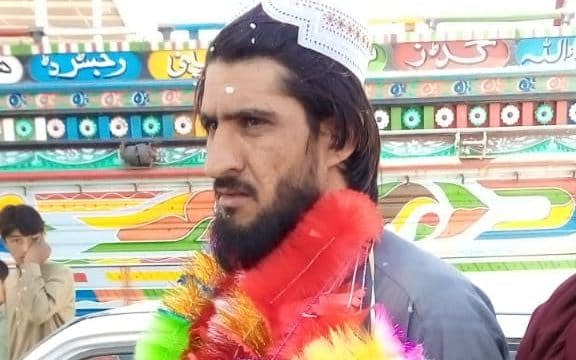

More than three years inside Afghanistan's most secure prison have done little to weaken Sher Agha Muhammad Khan's links to the Taliban.

When the 33-year-old was freed last month in a prisoner swap, one of the first things he did was visit his former militant commander.

“I was warmly welcomed, got some financial support and the Taliban promised us that due to my sacrifices, they would give me agricultural land,” he told the Telegraph last week by telephone.

His capture, a brutal interrogation and then sentence inside Bagram prison north of Kabul have taken their toll and he wants to return to a simple life on the land, he said. Yet if he was called on to rejoin his former comrades, he would not hesitate, he claimed.

“Before jail I was not an ideological Talib. Now I am,” he said.

“I was in Karachi to visit a doctor, because I feel psychological stress. I will start working as a labourer to earn for my family, but if the Taliban need it, I will be more than happy rejoining them again.

“We suffered for the sake of Islamic law in Afghanistan and that should be accomplished at the end of the day.”

Sher Agha is one of some 4,000 Taliban prisoners freed by the Afghan government since April, in return for around 750 policemen and soldiers released from militant jails. The swap laid out in February's accord between Washington and the militants will eventually see Kabul free 5,000 insurgents and the Taliban free 1,000 government forces. That will pave the way for the foes to sit down for the first formal talks to try to find a political end to Afghanistan's four-decades of war.

What men like Sher Agha do next will be closely watched by Kabul. Each has signed a pledge they will not return to the fight.

Sher Agha says he was forced into the Taliban by a local dispute in the Khawajah Bahawodin district of Takhar province. His ancestral land was seized by a local warlord called Malik Tatar, who has faced many similar accusations and denied them. The courts and government were no help and for years Sher Agha had no recourse to justice until the resurgence of the Taliban offered the chance of vengeance.

“We had no other option except to join the Taliban and take revenge,” he said.

He said he spent a few months with the Taliban, but claimed he had taken part in no attacks.

When he was seized at a road checkpoint, police who beat a confession out of him had photographs of him posing with other Taliban, suggesting they had an inside informant.

Sher Agha says he wants a peace process to succeed. “I love peace and I would love to see a regime in Afghanistan after a Taliban and Afghan government deal, I would like to go back to Afghanistan in peace and dignity,” he said.

He, like other freed prisoners, says he wants an Islamic government however. What that means and how far the Taliban's goals have moved from their repressive theocracy of the 1990s is still unclear.

“I am firmly against the foreign invaders and support anyone who stands for pure Islamic rules,” said Muslim Afghan, another recently freed militant.

The 27-year-old from Paktia province was a student at a Kabul university when he was seized six years ago and given a 15-year sentence. Prosecutors told the Telegraph he was linked to two bomb attacks south of the capital. He claimed he was framed and never took part in attacks.

His time inside Kabul's high security Pul-e-Charkhi prison was spent surfing the internet on his phone, he said, and he now wants to resume his studies. He said there was a clear direction from the Taliban that freed prisoners must not return to fighting. Many Afghans are sceptical.

Bartering over the releases has now reached a hardcore rump of prisoners that Kabul refuses to free because it says they are either plain criminals, or guilty of particularly horrific atrocities like the 2017 bombing of the German embassy that killed 150 civilians.

Muslim Afghan said the insurgents did not need the released prisoners to join their military efforts.

“The Taliban has enough men,” he said.