Rekha Basu: Signing off with thanks after 30 years of a dream job

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

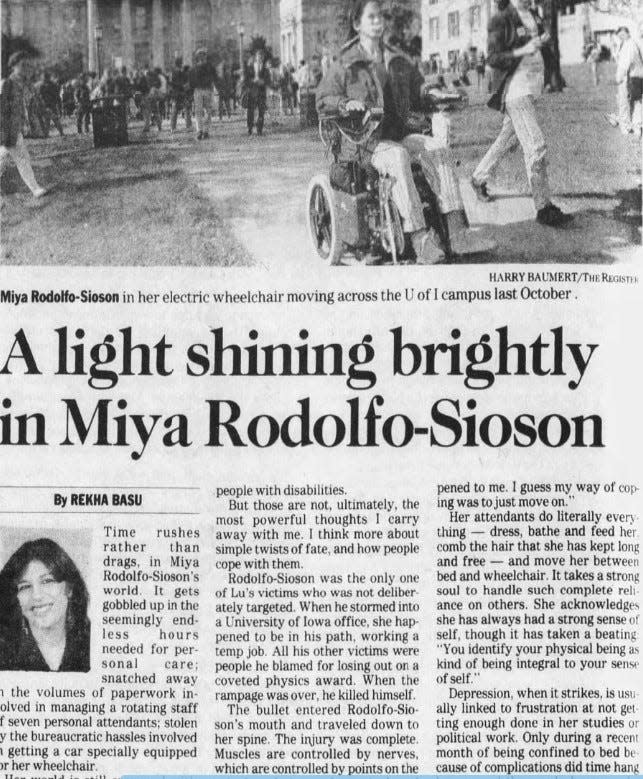

I started work at the Register Nov. 4, 1991, three days after a disgruntled University of Iowa grad student opened fire in a department office, killing five of his six victims, including himself. The lone survivor was Miya Rodolfo-Sioson, a 23-year-old student and temp in the office that day, who was left paralyzed from the neck down.

When I later interviewed her, a passionate, idealistic young woman committed to seeking justice for Central America, she had every reason to be angry or despondent. She needed attendants to do everything; her only control was through a mouthpiece. Yet she felt privileged to still be alive, continuing to work toward her cherished causes and nurturing hopes of someday traveling abroad, getting her master’s, marrying and adopting kids.

Meeting her changed me, as countless encounters with sources have done in the 30-plus years I’ve written columns here. Her resilience and acceptance of what she couldn’t control are traits I’ve come to associate with many Iowans, an attitude occasioned perhaps in some cases by the vagaries of farm life, like the unpredictability of rain.

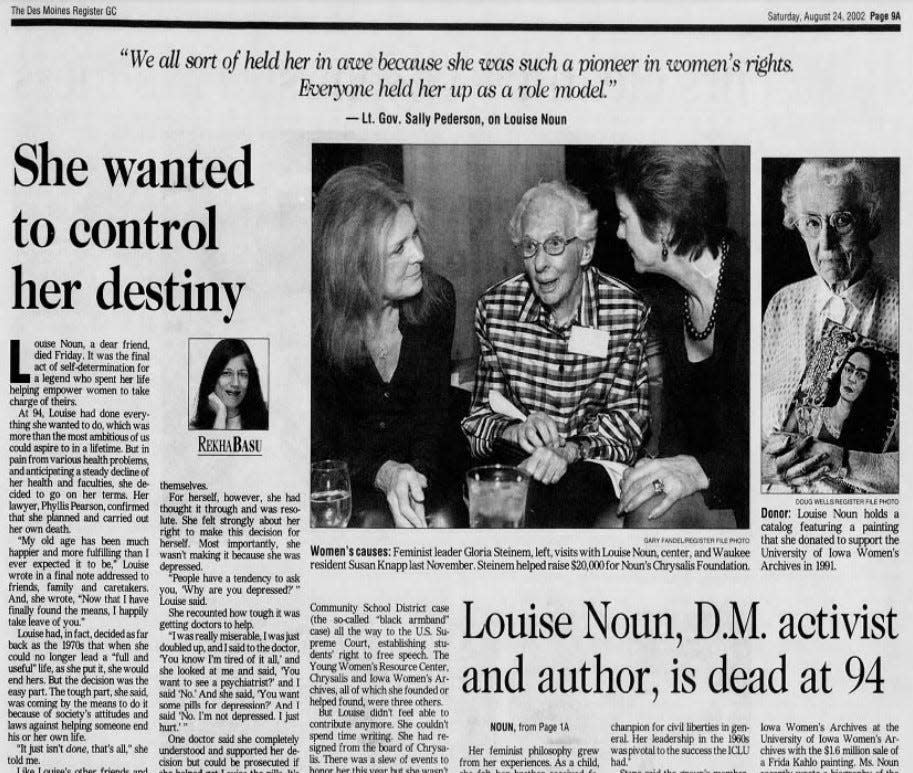

But if Rodolfo-Sioson’s wish to keep living taught me one lesson, my friend Louise Noun’s wish to die, which she shared with me in confidence in 2002, was a different wake-up call. She was hoping I’d take up her advocacy for the right to assisted suicide. But I had long believed that if a friend tells you of plans to end their life, it’s your job to prevent that by whatever means.

At 94, of sound mind yet facing increasing bodily infirmity, the feminist philanthropist, free-speech advocate and author had done all she wanted to, and was ready to go. She planned to check out as soon as she could find a method of doing so and wanted me to write about it only after she was gone. Meanwhile, I had to keep it a secret, even from my husband and mother. I tried to argue that she still had much to contribute, and that I’d miss her greatly. She had to remind me this wasn’t about me. And ultimately I had to learn to accept her decision for the same reason I believe a woman must have the right to choose whether or not to bear a child. It was her body and her choice.

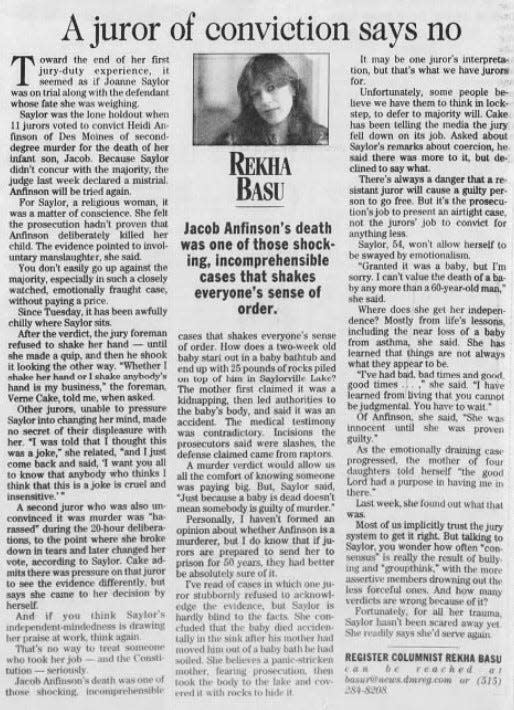

Now, as I leave this job, I think back on some of the ways it has forced me to rethink some of the values I held as absolute. Because every opinion column you write is a statement of values. And sometimes figuring out where you stand requires digging deeper — both into the story and into yourself. A very different sort of death that haunted Iowans in the '90s was shrouded in ambiguity. A mother was charged with second-degree murder in the death of her 2-week-old son, and sentenced to 50 years in prison. At first she had claimed she’d left him unattended in a bathtub. Suspicion naturally mounted when she led investigators to the site of his body, buried under rocks in Saylorville Lake.

But why? By all accounts, Heidi Anfinson was a loving mother who had wanted this child. Her husband was on her side.

There’s little support or empathy for mothers who gave birth only to face a severe crisis like postpartum psychosis, which Anfinson eventually acknowledged having, after serving 12 years of a 50-year sentence. That’s an extreme form of depression that can hit a woman after giving birth, bringing on hallucinations and paranoia. In England, greater awareness of it had resulted in the government not criminally charging a mother in her baby’s death within the first 12 months.

It would take a lone juror’s courageous refusal to go along with the other jurors’ wish to convict Anfinson of second-degree murder that ultimately guided my thinking. That juror may not have known the full story, but she knew enough to know Anfinson didn’t intend to murder her son. “A juror of conviction says no,” was the headline of my column. There would be another trial in which Anfinson was convicted and served 12 years in prison before she was paroled.

Writing opinions for a living in a community as connected as ours is a privilege and a risk, considering all the ways you could get it wrong. It takes some combination of head, heart and hard data to figure out where to land. Time after time in this job, I’ve had to challenge myself to look deeper, ask different questions of people involved, and remain open to changing my mind. Many times, my conclusions have angered some readers. But other times, the right answer has been clear as daylight. Yet some law enforcement official, legislator, doctor, judge or school board member, among others, did the wrong thing because of expediency, bias, cowardice, ignorance or expected benefit.

There was the low-income mother of two who drew a four-year prison sentence because of escalating traffic fines she couldn’t afford to pay. The more she drove to work to earn money to feed her kids, the higher the debt mounted. Denouncing the sentence, I wrote, “When she gets out as an ex-convict, she’ll have an even tougher time finding a job and making a living. Her network will be ex-offenders. Her children will have been raised without a parent. All so society could be safe from a poor mother who couldn’t pay her fines.”

There was the Madison County domestic-violence survivor whose ex-husband broke a restraining order by going to her home at night and trying to suffocate her. Police were called. He was charged, but not with violation of the no-contact order. Yet incredibly, she was charged with aiding and abetting violation of a no-contact order. Asked about this, the Madison County attorney lectured me on how women shouldn't let themselves be victims. Years later he himself would be charged with domestic abuse.

There was the Carroll High School teacher who lost her job of 15 years after police raided her home and found a small amount of pot belonging to her son. Yet she was forced to move south where she had family, to start over again. The column decried the unfairness.

“Where is Des Moines women’s anger about social issues?” asked one of my early pieces after a local judge at a judicial conference quipped in public remarks about using part of a woman’s anatomy as a vase. Why couldn’t Iowa pass the simplest amendment to its constitution asserting the equality of men and women? Why was no one publicly standing up for choice when a Planned Parenthood sponsor was intimidated by anti-choice groups into pulling its funding from rural health clinics?

I heard anger from all sides. I learned of some of the institutional blockades to collecting back child support, the workplace pay differentials, the sexually abusive high school coaches who had townspeople on their side because they coached local teams to wins. I saw the stigma women often faced for speaking out.

The unlikely path to Iowa

BACK IN INDIA in the 1960s, a palm reader shook his head and clucked while looking at the line on my hand associated with ambition. He saw none: a successful marriage, two fine children but no substantial earnings — most likely linked to my complete absence of goals.

He was right, at least for that moment. A diffident, rebellious kid uncertain of her role in a family of accomplished people, and of her identity in two different cultures, I dryly called myself an “international misfit.” In India I stood out as too American. Back in New York, I was too Indian. The one career path I was drawn to — acting — was mostly off-limits, as there were no roles for someone who looked and sounded like me. What I most cared about, learned from travels and talks with the family, was social justice. But as a foreign student attending the United Nations school, I was a guest of the U.S. government and forbidden from protesting the Vietnam War or marching for civil rights.

My colleague and friend Courtney Crowder beautifully summarized the unlikely confluence of events that led me to Iowa as an opinion writer in 1991. By then, driven to write advocacy pieces about marginalized people, I’d dabbled in the alternative press, gotten a master's in journalism and worked as a reporter at several daily upstate New York papers. I’d married, Rob Borsellino, the editor of the first one. As a reporter, I had to work almost as hard at editing out my opinions. But after my last reporting job ended when the paper went under, I returned to doing what I loved: writing opinions for the alternative press. And as karma would have it, I was recruited by the daily Schenectady Gazette in my ninth month of pregnancy to be an editorial writer.

Less than two years later, the Des Moines Register made national news by winning a public service Pulitzer Prize for giving voice to a rape survivor. Then a chance meeting with the paper’s opinion editor, Dennis Ryerson, at a national conference solidified my admiration for its editorial stances. So the following year, when I spotted a job opening there for an editorial writer, I jumped on it.

I moved here with two sons, expecting to stay at most two years. There was no job here for my husband at the time, and anyway, I wasn’t used to staying places more than two years. One of the boys was still in diapers; the other in kindergarten. So when a Realtor I'd enlisted to find me a rental recommended I buy property in the Roosevelt High School area so my kids could go to high school there, I laughed. We'd be long gone by then, I said.

I ended up not just attending Raj's and Romen's Roosevelt graduations, but being the guest speaker for both of them. I also wound up addressing the 2008 graduating class at Grinnell College, where a ceremonial scarf was draped around my shoulders as an honorary doctorate recipient.

I've outlasted seven Register publishers. In my time here, I became a naturalized U.S. citizen, lost my husband to ALS, saw my older son, Raj, get married and, last year, become a father. In that time my younger son, Romen, transitioned from a job in the Obama White House to being a comedy writer in Los Angeles.

Because of this job, I got to interview Edna Griffin, Sister Helen Prejean, Gloria Steinem, Afghanistan's female activist "Zoya,” Temple Grandin, Maya Angelou, Michelle Obama, Bernie Sanders, Hillary and Bill Clinton, Elizabeth Edwards, Mia Farrow, Julie Andrews and Bette Midler. And to be interviewed by Rachel Maddow, Don Lemon and Tom Brokaw, among others. I shared a hot tub with Molly Ivins at a women’s writers retreat, and a hug with Gabby Giffords in a downtown Des Moines coffee shop. I hung out with openly gay Crown Prince Manvendra Singh Gohil of India after Nate Monson, who led an Iowa organization for gay youth, asked me to moderate his visit to Des Moines. I gave author Carl Bernstein my garage door code when he called one evening wanting to meet to pitch me on his new book about Hillary Clinton. So by the time I got home with friends I'd been out dining with, he was already settled in, having a drink.

Steps backward and forward, and what comes next

SADLY, SOME THEMES to my columns have persisted, involving the mistreatment of African Americans, immigrants (predominantly Muslim) and the LGBTQ community (predominantly transgender). Moving here in '91, I was struck by the degree to which gay and lesbian people felt unsafe coming out, in part because of the absence of civil rights protections based on sexual orientation. That finally changed with an addition to state law in 2007.

But before that, 12-year Des Moines school board member Jonathan Wilson was voted out when it became known he was gay. And nine years after that, in 2004, the state Senate's GOP majority blocked Wilson's appointment to the Iowa Board of Education, explicitly for the same reason. Said Republican Sen. Ken Veenstra, "This … is the wish of God-fearing people that insist on basing their values on a divine law rather than a misguided culture that man has created."

As recently as 2003, a popular local talk-radio host was regularly calling a school's Straight and Gay Alliance the “sodomy club” and a gay person a “pervert,” and chiding the school for pushing sexual activity and homosexuality by allowing such clubs. And even though Iowa got same-sex marriage in 2009, the Legislature and governor continue to rally constituents using false fears over LGBTQ-affirming books at school and transgender people's bathroom use or choice of sports teams. Also triggering controversy and parental protests has been the supposed teaching of critical race theory and the 1619 Project.

One of my proudest moments as an Iowan was seeing America's first Black president get his first nod in the 2007 Iowa caucuses. I'd hoped Hillary Clinton would run and win four years earlier. But almost by accident I got to hear Obama address 18,000 people at Hy-Vee Hall and instantly knew he was the one. I'd already met and talked to him at editorial board meetings. But never before had I witnessed so viscerally the commanding charisma he showed or the ability to inspire people to dream bigger.

So after the Register officially endorsed Clinton, I weighed in for Obama, describing him as "that rarest of leaders, combining roots in white Midwestern America with black Africa, and experience both organizing in barrios and editing the Harvard Law Review.” As I wrote, “It was as if no one could quite believe this youthful but commanding man, who spoke their language and echoed their dreams, might actually run America.”

The day the piece came out, Michelle Obama, with whom I'd had coffee, called me elated, saying she'd just gotten off a plane when someone handed her my piece. Iowans started writing me to say the column had persuaded them to vote for Obama. And on the day of the New Hampshire primary, which followed Iowa, Obama himself called my house and left a voicemail thanking me for the column, and saying he thought it helped him.

Things like that could happen only in Iowa, I would tell friends elsewhere. Now Iowa Democrats apparently no longer have the first-in-the-nation caucuses, and Iowa opinion writers may never again have that power.

My own career trajectory has been notable for its lack of long-term planning, and for being motivated more by emotion and impulse than by the prospect of money or power. Yet I leave feeling empowered by all the things I was able to do here. I hope my unlikely path will encourage some young person uncertain of their goals in life to worry less, and be guided more by their passions: Harness that anger, outrage, alienation and grief into a career path. Use the sensitivity you may have been teased about as a strength. Take risks to do what you love.

Today, as I leave this job, I think back to what that palmist said about my lack of ambition and am finally able to declare him wrong. I did lack a career path back then, or at least the imagination to picture a future. I was uncertain of my place in this complicated world. But what some call ambition or career drive might really just be indignation that spills over into constructive callings. Those things can embolden us and give us purpose and drive.

And finally: With each big life event, people ask if I'll be leaving Iowa. Once again I don't know what the future looks like. I hope to keep writing and speaking out in some form, maybe through another medium like radio or TV. But I know this much: Des Moines is still home. And whatever else changes at this paper I've devoted myself to, it still has important truths to tell, and talented people to tell them, so I hope you'll keep reading it.

Rekha Basu is an opinion columnist for The Des Moines Register.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Rekha Basu is signing off with thanks after 30 years of a dream job