The Re-released Paris Is Burning Brings Us into the Future

The new restoration of the legendary drag-ballroom-culture documentary Paris Is Burning, directed by Jennie Livingston, looks gorgeous and sounds momentous. All sequins sparkle, lights shimmer, details pop, voices boom, music pulsates, and queer life itself bursts with as much joy as struggle to find what joy might mean in an oppressive world. Re-released by Janus (sibling company to the Criterion Collection) on June 14 at New York’s iconic Film Forum (at which it made its New York premiere in March 1991), in time for WorldPride and Stonewall 50, Paris’s return to theaters gives a new generation of viewers the chance to be transported back to the late 1980s and to engage with a part of queer history again. Hypothetically, at least.

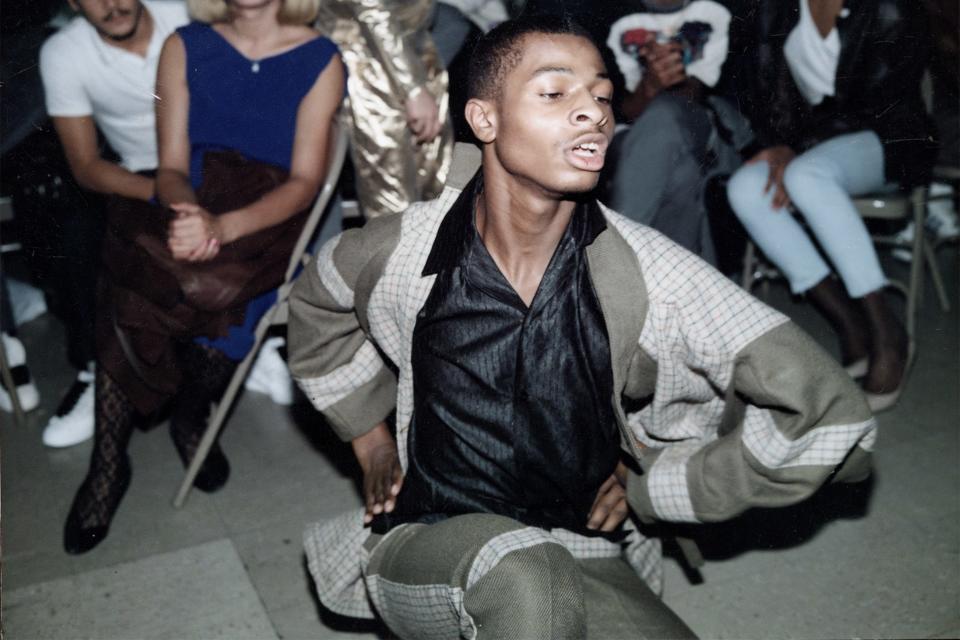

Thrusting the audience into the drag-ball scene of Harlem in 1987, populated mainly by queer and trans youths of color trying their best to survive, Paris Is Burning takes an anthropological approach, breaking down the social routines, habits, and hierarchies within the culture. Simultaneously, Livingston follows the lives of several within the community, from vogueing master Willi Ninja to experienced pageant queen Dorian Corey—who gave us the now iconic definitions of “reading” and “shade” (and also had a mummified corpse in her trunk)—as well as younger members from the House of Labeija and the House of Xtravaganza.

In interviews with trans women like Venus Xtravaganza (who was sadly murdered before the documentary was completed) and Octavia St. Laurent, Livingston turns an empathetic eye on their dreams, aspirations, and desires. They not only want to live in the world like everyone else, free of the marginalization that trans women of color face disproportionately, but they want to be famous, rich, and influential. Their American Dream is not merely wealth but a transcendence of their current class status.

In the age of social media, in which the impact of RuPaul’s Drag Race has created a kind of “drag industrial complex” (look at DragCon on both coasts for starters), Paris Is Burning carries with it a kind of implied ubiquity, very broadly speaking. Its images, its terminology (see: “shade” and “reading”), its bodies in movement (images of which were first popularized—or pilfered, depending on whom you ask—by Madonna in 1990) are GIFed, thrown around on social media, mimicked and re-created in videos, frequently by those outside of the ball community. Paris Is Burning, as a queer text or a documentary, has built a legacy based on iconography, rather than on being an actual film people watch.

That might be, for better or worse, the fate of cultural objects whose elements proliferate freely online and are beyond somewhat decontextualized. Certainly, part of the goal in re-releasing Paris Is Burning in theaters is to reignite the conversation around the film, and around how our conceptions of queerness and drag have changed in the time since. Additionally, there is an opportunity to examine how the spaces we occupy have or have not changed. Perhaps to revisit a film like this is to interrogate how the lives of those within the community who are most marginalized or at risk have changed—or how they haven’t.

A handful of other queer cinema landmarks are also seeing re-releases—like Frank Simon's The Queen (Paris’s spiritual older sister, screening at IFC Center beginning June 28), about the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant and starring drag icon Flawless Sabrina, and Derek Jarman’s The Garden (which ran at Metrograph Pictures the last week of May). But many of these festivities seem somewhat limited to New York.

Many strides have been made in terms of pop-culture visibility for queer and trans people of color, but despite this increased representation, much of queer media is still dominated by cisgender white people. Paris Is Burning has always felt like the “well, but there’s...”—the exception in a conversation about the limited imagination in depictions of queer lives. But the film should really be just a starting point for a growing, evolving approach to gender and sexuality in pop culture.

But the problem Janus and the legendary film itself run into is, as aforementioned, one of access. Paris Is Burning has hopped on and off Netflix’s streaming service since 2011, but its DVD, released by Miramax and most recently reissued in 2012, is out of print and can currently be bought on Amazon for $319.95. Without a consistent platform or form of delivery, it feels like a not atypical form of marginalization by the market, not to say anything of the fact that those who might best benefit from seeing Paris Is Burning—other queer and trans people of color—might not have the resources to see it: They might not live in New York, or be able to buy a ticket (Film Forum’s tickets are $15 each for adults), or have Internet access.

Janus’s theatrical re-release, which began expanding across the country, from Atlanta to Athens, Ohio (with a total of 32 cities), on June 21, will almost certainly lead to a physical release by the Criterion Collection on Blu-ray and DVD (no official announcement has been made); their releases run $40 at SRP.

Writer Willow Maclay illustrates the problems with access in her conversation with writer Caden Gardner, noting, “The thing about art about outsiders and minority groups is that it usually ends up out of our reach, and with the death of the video store and homogenization of streaming options with Netflix's near monopoly it gets even dicier, unless you're torrenting your own history.” The structural and systemic reasons for this are disheartening, from underfunding to a supposed logic that prioritizes box office over potential influence. And the end result means far too few ways to access pieces of culture so pivotal to our shared history.

The strange thing about even writing about “the access problem” with this film, or any other outsider or independent art, is that we live in the age of the Internet, where old, weird foreign movies are easily found on any number of tube sites (though perhaps through less than legal means). People go about finding alternative ways of accessing this work online via torrenting, too. But these forms of access make it harder to create community, which can enact real, tangible change.

No matter how far representation gets in pop culture for queer people, it is crucial that a sense of community exists for the rejected and marginalized. Movies have the power to create bonds between people, but in a paradoxical cultural and political climate where Pose can get renewed for a second season but the safety of trans women is still in threat, the re-release of Paris Is Burning as a community-centered project is the film’s most applicable lesson. Rather than have the film exist randomly in a vacuum on a streaming site, we can provide opportunity for the interrogation of representation, collaboration, exploitation, documentary ethics, and the successes and failures in the modern LGBTQ rights movement's handling of its trans siblings.

All film has the dormant power to bring people together to share an experience, but Paris Is Burning and other queer films like it struck a nerve in me even before I myself came to identify as queer. There was a limitlessness, an explosive beauty and a rejection of what could be considered good taste or convention. History could be both documented and turned on its head to reveal new kinds of lives and ways of being. Paris is one in a litany of films that sparked my obsession with interrogating and exploring what queerness could be on screen—and how that reflection of ourselves could expand our own sense of identity, and let us conceive of what it meant to live in the world as an “other” and reclaim that space both in the real world and in the cinema.

There is a hope, one as utopic as the spaces of joy and freedom featured in Paris Is Burning, that institutions like libraries and maybe even schools will invest in making such a film, and other queer art, more available to people. That a revival will encourage educators, activists, and everyday people to even go beyond this one film and share the work of black gay filmmaker Marlon Riggs (Tongues Untied) and lesbian filmmaking pioneer Barbara Hammer (Nitrate Kisses) and others. My hope is that the re-release will encourage curiosity beyond the limits of what one movie theater in New York or a major streaming service has to offer. This year’s Pride Month coincides with the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising and, in New York, WorldPride. It’s the perfect opportunity to let the reflections of ourselves from the past help shape the queer future.

Originally Appeared on GQ