Relics of racism belong in museums, not on Kansas City street signs | Opinion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Kansas City should commission its own museum of evil. We’re serious: Why not take a cue from Harlan Crow, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ eccentric and well-connected benefactor? Create a collection of educational monuments dedicated to prominent area slave owners — and get their names off our streets.

Billionaire GOP donor Crow installed a sculpture garden of fallen communist dictators — Lenin, Castro, Gottwald — in the yard of his Dallas mansion. Not to revere them, he says, but to document and remember the horrors of their abuse of power.

If one of the most prominent conservatives in America can keep notorious figures from the past in proper context, Kansas City must do the same.

In a place rich in cultural centers, museums and other exhibit spaces, Kansas City leaders must develop a plan to rid the city once and for all of street names, monuments and other public symbols that honor slaveholders and others who participated in the oppression of Black Kansas Citians and other minorities.

And for all of those worried about erasing history: No, their names and achievements must not be forgotten.

We could start with John Wornall. Despite once owning six slaves, Wornall has a major street in Kansas City named after him. But should he?

How about Allen B.H. McGee, a Southern sympathizer who owned at least five slaves? He is honored, too. At 54, McGee married a 19-year old woman. Age gap aside, McGee’s father-in-law owned at least 20 slaves. Why does a Kansas City street still bear his name?

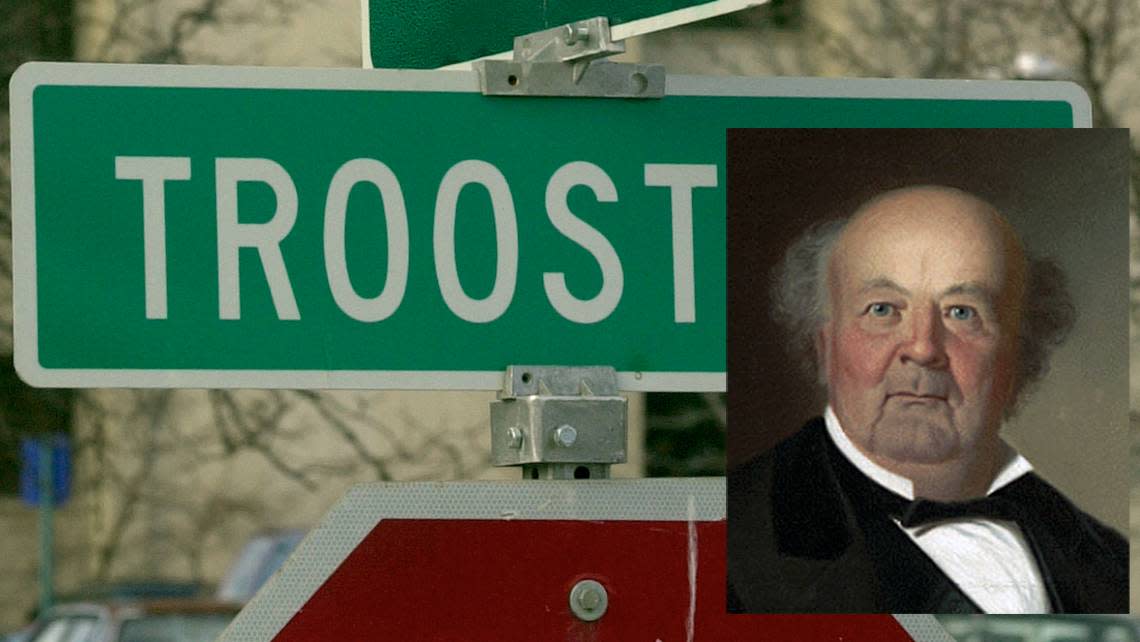

And we can’t forget hotel owner, publisher and physician Benoist Troost. The Dutchman was a slaveholder, too. And there are many more streets with controversial pasts that need examining. But a push to rename the street named for Troost is moving ahead.

On Thursday, the City Council approved a resolution directing City Manager Brian Platt to create a landing page for the proposed renaming process for Troost Avenue. As with any move this controversial, input from Kansas Citians, business and property owners is paramount. Platt and staff have 45 days to report back to the City Council with their findings. We remain hopeful they will make it easy to submit testimony.

Bring some Truth to Troost Avenue

Make no mistake, Troost Avenue has long been known as Kansas City’s dividing line — ground zero for the city’s history of racial segregation and slavery.

Troost, one of Kansas City’s founding fathers, owned six enslaved men and women in 1850, Kansas City Public Library records show. Renaming Troost, Kansas City’s boundary of racial separation, should be a no-brainer, former parks commissioner Chris Goode said.

Goode owns a business in its 3000 block. He wants to rename the thoroughfare as Truth Avenue. He started an online petition, held public forums, engaged stakeholders and raised money to fund the movement. He has support from 3rd District Councilwoman Melissa Robinson, who sponsored the recently-passed resolution.

No matter the name, Troost Avenue or any other symbol tied to racism and slavery must go, Goode said. “In Kansas City, we can’t continue to celebrate people that owned people,” he said. We find little fault in this argument.

During this conversation, city officials must consider the importance of engaging the public. We remember the steps community activists skipped when The Paseo was renamed after slain civil rights icon Martin Luther King, Jr.

Eyebrows were raised when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard signs were installed without the proper buy-in from property owners along that stately parkway. The premature misstep cost taxpayers tens of thousands of dollars when voters swiftly and overwhelmingly changed the name back and the signs were taken down. Eventually, a 5-mile stretch of the former Volker Boulevard and Swope and Blue parkways were named for King — a move long overdue in one of the last major cities to bestow that honor.

Because, obviously, it’s a major public statement. Naming a street after someone equates to a city’s endorsement and celebration of that person. Yet each day, Kansas Citians are reminded that people who once claimed others as property still enjoy public commemoration and honor.

“Forget the street name, that is a distraction,” Goode said. “The people that stole the identity of Black people should no longer be honored anywhere.”

Push to rename streets, monuments dropped

Three years ago, amid the national come-to-Jesus moment of racial reckoning, Kansas City took the bold step of stripping the name of prominent real estate developer J.C. Nichols from a parkway and fountain near the Country Club Plaza. Goode was at the forefront of that movement. Nichols’ pioneering system of race-based deed restrictions was instrumental in creating Kansas City’s racial divide, local historians note.

So why stop there? While the road is now Mill Creek Parkway, the fountain at Mill Creek Park remains nameless, an oversight the city parks board must address.

The same year, the City Council approved a resolution requesting the parks commissioners to develop a comprehensive strategy to remove memorials and symbolic monuments honoring slave owners, racists and those who participated in the oppression of others.

Under the direction of Jack Holland, parks board president, the renaming movement went nowhere. In March 2022, Holland admitted in a public meeting that the board was no longer considering a plan to rename streets and other memorials tied to racists.

Nobody is suggesting that Kansas City censor its heritage. To the contrary, our suggestion of a museum of our forebears’ failings — The Star’s own included — would help tell that story better. And it isn’t a new idea. Grutas Park near Druskininkai, Lithuania, commemorates its harsh authoritarian rule under the USSR by relocating area statues once meant to lionize Soviet leaders together in one place, along with depictions of the horrors of the Gulag.

Harlan Crow is a collector of historical artifacts. Even if we don’t fully understand his garden of evil, he models a reasonable way to preserve some of the dark passages in our history.

Will Kansas City officials follow suit?