Religions alter death and burial rituals in wake of coronavirus, causing mourners more heartbreak

Of the dozens of funerals he’s presided over since coronavirus ripped through New York state, killing more than 15,000 residents and infecting more than 263,000 – and ravaging the Jewish Orthodox community in particular – Rabbi Levi Gurkov was struck by one ceremony.

Gurkov, who leads Chabad of Oceanside, an Orthodox synagogue on the south shore of Long Island, didn’t want to give details about the mid-60s widow, insistent that she be allowed to process her grief privately. But he can’t stop thinking about how alone she was, mourning the loss of her husband in a solitary, heartbreaking manner.

“This woman, there was no one there to give her support,” Gurkov recalled. “Her very good friend couldn’t come to the funeral because she was worried about exposing herself, her children were quarantined in another state, other friends and family were in the hospital. She was just all by herself.”

He described a piercing loneliness in the room, a shattering, solitary grief that was made worse by how singular it was, because it fell solely on the shoulders of the widow, and Gurkov, who couldn’t even offer the woman a hug. “I’m trying my best to be there for families, but …”

His voice trailed off. The grief is overwhelming, he said. It feels endless.

Faith leaders have had to shift roles – Gurkov joked that he’s now a part-time health administrator, distributing glove and masks anytime people do attend funerals and making sure everyone stays at least 6 feet apart. They try to answer deep, theological questions about the afterlife from panicked congregants. Because of orders that limit the number of people at funerals and require physical distance between residents, many death and burial rituals have been modified.

An act of God?: Faith leaders debate tough questions amid coronavirus pandemic

Both Judaism and Islam instruct believers to bury bodies as soon as possible, typically within 24 hours of death. Bodies are claimed from morgues or hospitals immediately (cremation is strictly forbidden in Islam and traditionally forbidden in Judaism) and washed before burial. In a world where stay-at-home orders are commonplace, that’s not always possible.

In Long Island, Gurkov said at least one prominent funeral home said it won’t do Jewish burials in an effort to protect its employees. That ritual includes wrapping the body in linen and making sure the body is watched until it’s put in the ground. Typically, the deceased are never left alone. The number of bodies makes that almost logistically impossible now, Gurkov said.

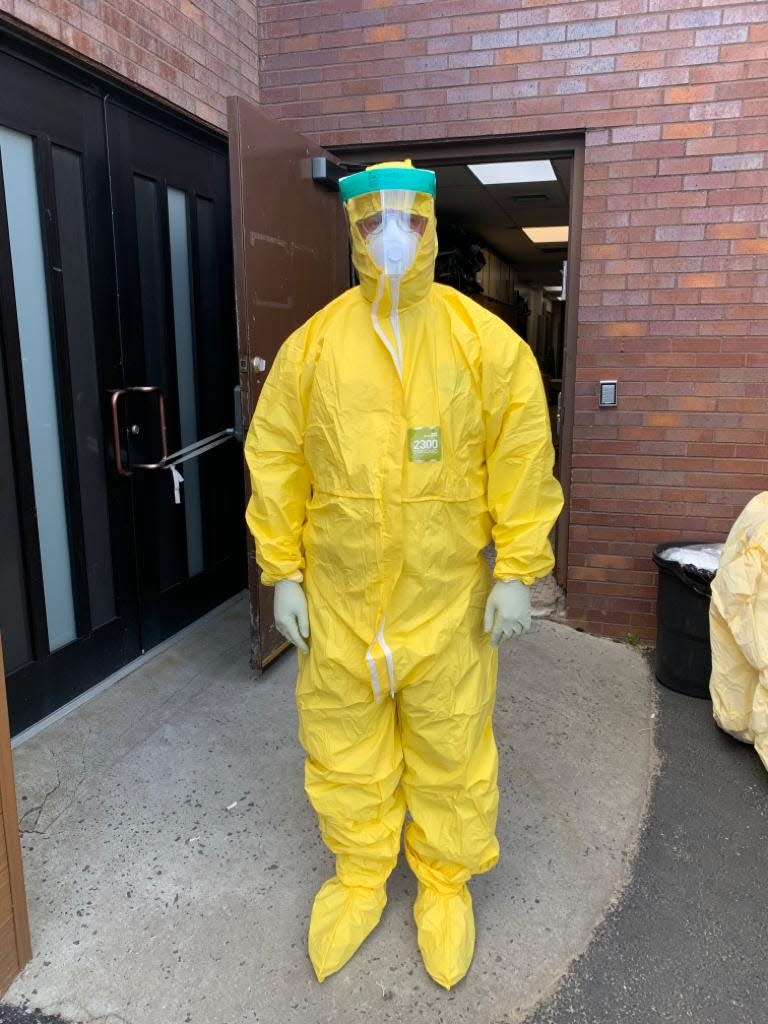

Gurkov works as a volunteer at the Chevra Kadisha, a Jewish burial society made up of volunteers who prepare bodies for burial using “the utmost respect and care as mandated by Jewish law,” according to Gurkov. To perform this work, he protects himself with a hazmat suit and the proper headgear. He’s been busy, averaging five funerals a day.

Although Gurkov has yet to counsel a family that’s been unable to obtain a Jewish funeral, he knows other Jewish societies and rabbis across the world are dealing with that very problem, and the anguish that accompanies it.

Gurkov is adamant that there’s no reason for anyone to worry that God will be angry about a modified ritual. Gurkov hears from loved ones left behind that they’re desperate to do the right thing and heartbroken to think they might let down a loved one who’s died. There's anguish that they might shortchange someone's soul. Gurkov tries his best to comfort them – from a distance.

“I want those people to know, that I’m holding their hand virtually through this, and so is God,” he said. “I tell them that their fears are understood, but they shouldn’t beat themselves up. There is nothing to fear. Whatever anybody is able to do at this time, if it’s the best we can do, that’s what’s warranted. God understands this is not in our control.”

In Washington, Imam Johari Abdul-Malik gives Muslims the same message – that a modified burial will not affect the afterlife, and Muslims should not be anxious for those who have died. He aches for people who lost a loved one and are forced to mourn by themselves.

“For the most part, funerals are not about or for people who died,” Abdul-Malik said. “They’re for the people who remain. The ability to collegially grieve is really important. Not being able to provide that comfort for people is gutting.”

'We hear you, Dad': A daughter stays on phone for hours as her father dies alone

In Islam, Abdul-Malik explained, public viewings of the dead are traditionally discouraged, but immediate family washes the body – a great honor within the faith – and dresses it in shrouds. Then Muslims pray the Janazah, the funeral prayer asking God to pardon the deceased and all other Muslims. Included in the prayer is the line “To Allah we belong, and to Allah we shall return.” According to Abdul-Malik, the Quran says having three rows of people praying the Janazah is “a great blessing.”

In the age of coronavirus, when remains are delivered in a double-sealed plastic bag – which means there’s no opportunity to view a loved one – and when funerals are limited to 10 people or less, these things are not possible, which compounds grief. People who lose someone in any manner, coronavirus-related or not, often feel guilty, Abdul-Malik said. One way to compensate for that guilt can be to hold a giant funeral. These days, that’s not happening.

“These losses,” Abdul-Malik said, “are on so many levels.”

The past few weeks, as death tolls have risen, the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), the nation’s largest Muslim advocacy and civil rights group, started hosting daily video chats addressing various coronavirus topics, including how to deal with burial and funeral rituals and restrictions.

On March 20, Imam Suhaib Webb explained that although Islam’s burial rituals are typically considered a “communal obligation,” there’s an overriding principle in the faith that if people performing those acts are put in danger, the rituals can be dropped or modified. As for the notion that Muslims might be ashamed they can’t follow through with their traditions, Webb said imams and other leaders “need to be in the role of ministers, not lawgivers,” and focus on caring for those in mourning, not scolding them for something they can’t control.

In Los Angeles, that’s been the focus of Amy Bernstein, senior rabbi at Kehillat Israel, a 1,000-family synagogue, who serves as the president of the Board of Rabbis of Southern California. She’s concerned about people dying, but mostly she’s been thinking about those left behind.

“Yes, it’s sad that dead are not being honored, but the real tragedy for us as a people is that the moment of the burial, we shift to comforting the mourners,” Bernstein said. “Rituals around death are really powerful for all cultures. They’re huge transitional points … and right now, what’s really being stripped away is the ability to sit and grieve together.

“We are pack animals; we’re not designed to do most things alone.”

Jewish funeral homes in Los Angeles have limited burials services to 10 people, putting larger families in agonizing positions. How do you choose who makes the cut and who’s left at home?

For liberal Jews, there’s a lack of pallbearers. Typically at a Jewish burial, pallbearers lower the casket into the ground, then loved ones shovel earth onto the casket and pass the shovel around. Now, there’s no shoveling and no shovels, which means no final ritual.

“It’s awful to hear that thud of dirt on the casket, but that’s also the first step of closure,” Bernstein said. “Everyone shovels, because it is our responsibility. … To just leave the body above ground, that is not Jewish.”

The struggle for mourners, Bernstein emphasized, is emotional, spiritual and psychological. Sitting shiva wasn’t designed to be done via Zoom. It takes a toll on everyone, she said, and she’s preparing for it to get worse in the coming week.

In Judaism, it’s not traditional for a rabbi to be called to the bedside of a dying person, though that’s common in Catholicism, when priests are asked to anoint the sick – often referred to as last rites – and hear a final confession.

In Kirkland, Washington, where the first U.S. coronavirus fatalities were reported, Father Kurt Nagel was ready to receive a lot of those calls.

The lead pastor of Holy Family Parish has been summoned only once to Evergreen Health, the hospital where all critical Kirkland patients went. He’s kept busy the past few weeks assuring congregants that even if their loved ones weren’t able to receive last rites, that doesn’t mean they’re going to hell.

The afterlife is between a deceased individual and God, Nagel said, and it’s not for him or any other human to speculate on what happened to a particular person.

Nagel is concerned about those left behind but points out that because Catholics don’t have any rules or rituals tied to when someone needs to be buried or memorialized, most are waiting for social distancing to lift before holding funerals. He’s presided over only two funerals and anointed one person in the ICU.

Nagel was called to the beside of a sick senior citizen at the Life Care Center – where the first fatalities in the American outbreak were reported. The person he anointed was believed to be dying of heart disease, but it was later determined that she died of coronavirus. Nagel had to self-quarantine for 14 days.

In his absence, the Holy Family assistant pastor was ready to step in and provide comfort to anyone he could – from a distance of at least 6 feet.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Coronavirus forces religions to modify death, burial rituals