Remainers are convinced that Britain is irrelevant. They’re set to be humiliated

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If, as reports this week suggest, the way is now clear for Britain to join the CPTPP, a huge free trade agreement covering both sides of the Pacific Ocean, that is massive news. Kemi Badenoch deserves huge credit for it, but so does Liz Truss, who gave it the necessary priority as international trade secretary against much political and bureaucratic scepticism.

It matters because the CPTPP is where the growth is. With Britain a member, the CPTPP has the same GDP as the EU27. But it will grow much faster in future, increasing the benefit of Britain’s new access to the world’s most dynamic markets.

The CPTPP is of course a totally different organisation to the EU. It’s a genuine free trade area. It doesn’t have its own parliament or court, it doesn’t impose laws upon its members, and it is focused on opening markets, not harmonising and integrating. Trade specialists will say that this makes it less valuable as a trade agreement, but personally I prefer free trade plus national sovereignty. The fact that there are many free trade agreements around the world, but only one EU-style single market, suggests that most countries reach the same conclusion.

The CPTPP is important politically. Britain could not have joined as an EU member and it raises the bar to ever rejoining. So watch out for a big scare campaign from Remain Central to frighten us about food standards and ruthless competition, in the hope of delaying legal accession.

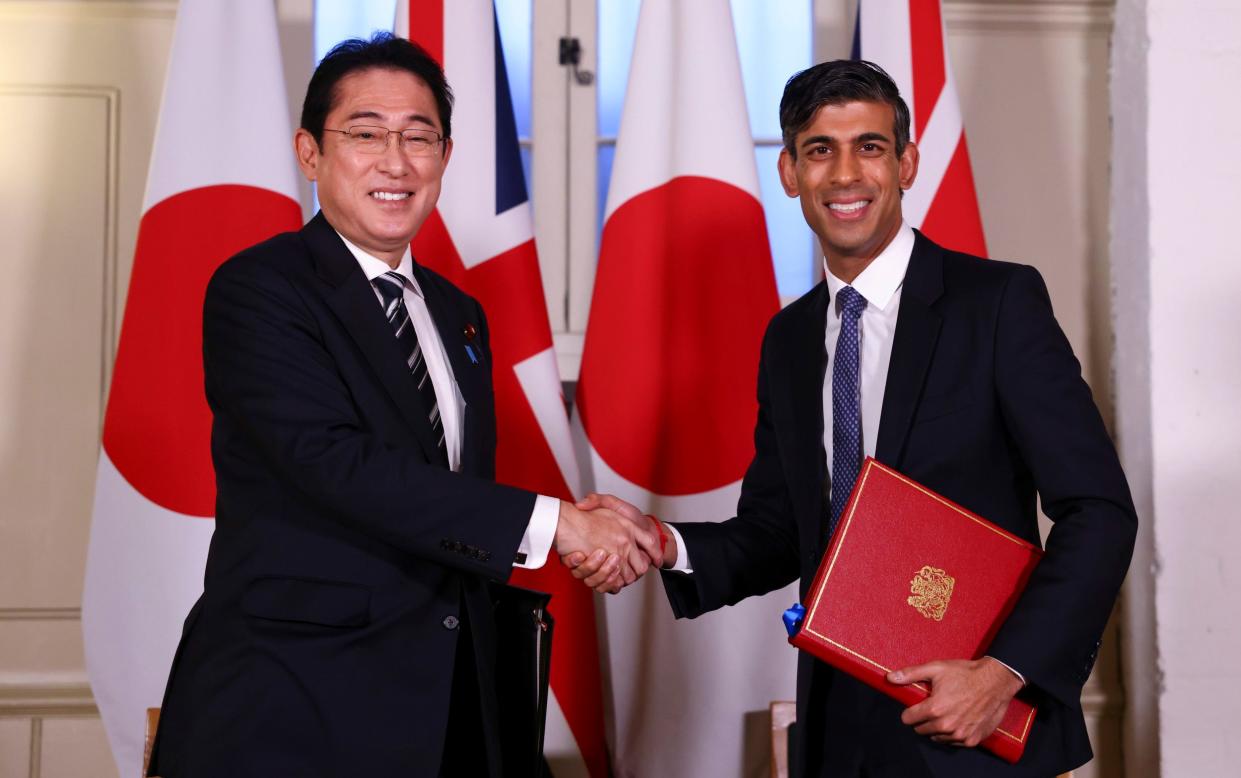

Finally, it is important for our foreign policy. Membership is a huge boost to Britain’s Indo-Pacific tilt. Together with our defence agreements with Japan, our carrier deployment, and our acquisition of close partnership status with the main Southeast Asian organisation ASEAN, it shows that the UK’s presence in the Pacific is not an anomaly but something that is very much welcomed.

Many mocked Boris Johnson’s “Global Britain” slogan and told us that Britain could not hope to establish a global role on its own. I think we can be confident that this judgment is now comprehensively disproven. It is in fact on foreign policy that Britain has most successfully marked out a different route after Brexit, one set out in last month’s refreshed Integrated Review of foreign policy – a rare intellectually coherent document coming out of government, thanks principally to the role of the excellent Professor John Bew in writing it.

To take just two examples. For the first time, we are able to balance our security against our economic interests with China, with a tougher (if not perhaps tough enough) policy as a result, freeing ourselves from the EU’s lowest common denominator trade-dominated approach. Indeed, joining CPTPP gives us a seat at the table on China’s own request to join.

Similarly, Boris Johnson saw what was at stake on Ukraine and in many ways led the global response to the Russian invasion. Who can really believe that not just our, but the European, Ukraine policy would have been more effective if Britain had had to spend all its time bogged down in meetings in Brussels seeking to persuade France and Germany to act differently?

Unfortunately not everything is right yet. The instincts of our foreign policy establishment to compromise and to spend time in process rather than action remain strong. The Integrated Review is clear that we are in an age of great power competition, but we have not entirely shaken off naïveté about what that means.

We are too deferential to international institutions, rather than seeing them for what they are: arenas for competition among the great powers. We still tend to believe that the international rules-based system is self-sustaining rather than dependent on American and Western power – which is why it is so disappointing that we have downgraded our defence spending “aspiration” to just 2.5 per cent of GDP.

And that matters. In the end a successful foreign policy ultimately depends upon economic success. Without that, we can’t sustain defence spending, and the way we do things is less influential with others. That’s why the achievements since 2019 are so impressive – but also potentially fragile.

Britain was at its most effective in foreign policy in the 1980s, when we were on the way up again economically, and again under Tony Blair, when we were growing faster than the rest of the EU. In both cases – whatever one thinks about the Iraq policy – it is hard to argue that Britain was not taken seriously as an international player.

So to sustain this foreign policy renaissance, it is crucial to bring back economic growth. It isn’t enough to run the country in a pragmatic, safe, unchallenging way, and to bask in the approval of the Davos and the Financial Times classes for doing so. Growth means reform, tough decisions, and change.

We aren’t yet seeing that. I worry about legislation on renting that will gum up the market still further. I worry about the persistent question mark over the plans in the Retained EU Law Bill to reform the laws inherited from the EU. Indeed, I predict that we will soon be told that this Bill needs amending to take account of the so-called Windsor Framework: this must not be a smokescreen for slowing the reforms or for dropping the 2023 deadline.

And I worry about our arbitrary, politically determined, and economically nonsensical net zero policy. Although yesterday’s announcements show some limited evidence of recognising the real requirements of energy security, there is no fundamental change of approach, and they include horrors like Soviet-style diktats on exactly what goods can be produced and sold by car manufacturers or boiler producers.

There are also proposals to develop so-called CBAMS, “carbon border adjustment measures”. Such new tariffs will not help growth. Moreover, it’s easy to see how the plans to discuss them with the EU could lead us into coordinating customs and tariff policy more broadly, perhaps with Northern Ireland as an excuse, and restricting us in conducting our own trade policy once again.

A crash into reality one day soon over net zero sadly seems unavoidable. But in other areas there is still room to get onto a better path by the election by pushing on with tax and regulatory reform. If we want to be strong, we’ve got to get rich again. It’s as simple as that.