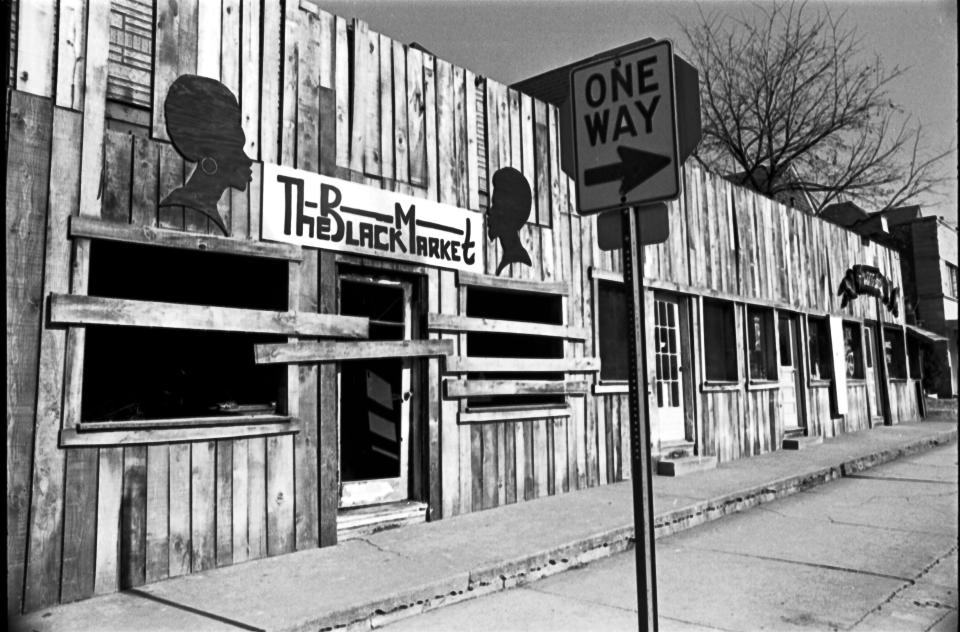

What remains of the Black Market after the 1968 firebombing

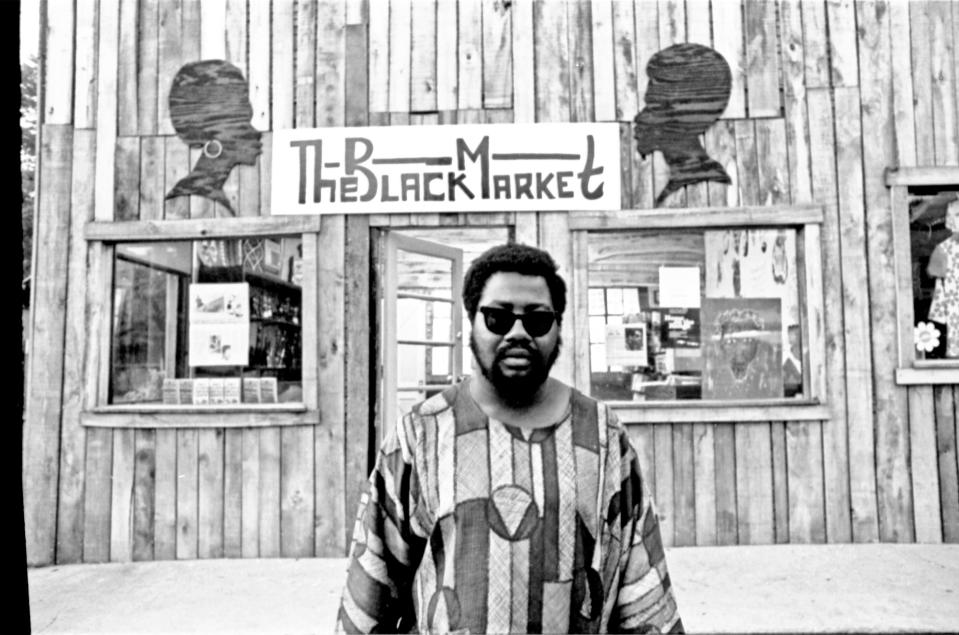

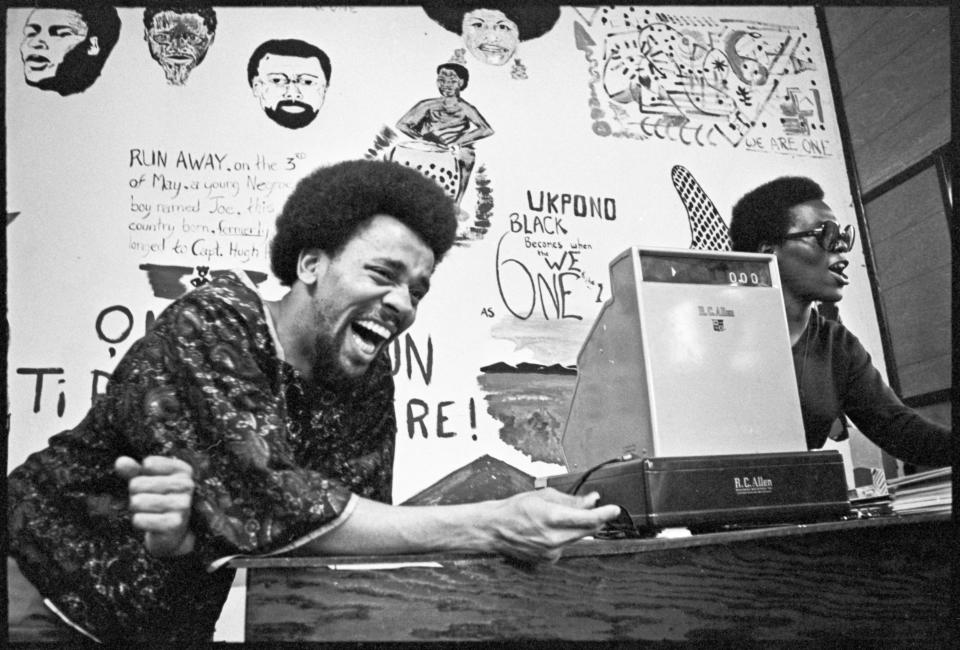

With walls of hand-painted refrains, stacks of vinyl records, and shelves of paperbacks, the Black Market made a splash in 1968 as one of the first spaces to incorporate and celebrate Black culture in the white-dominated, southern Indiana town of Bloomington. The shop was as much a marketplace of ideas as it was a place to shop for clothes, music and art made by African American vendors.

After being open for just three months, the Black Market was the target of a racially motivated firebombing, but its trailblazing legacy is engrained in the zeitgeist of life in Bloomington during the turbulent 1960s.

Life in 1968: Klu Klux Klan invasion attempt, Indiana University protests, FBI surveillance

Some notable events paint a stark portrait of what 1968 was like for the Black community. That March, Klu Klux Klan members from Morgan County tried to establish a local chapter in Monroe County by hosting a membership drive, which would have included a gathering on the Bloomington courthouse square and a march through the business district. The Monroe County prosecutor stopped the event from taking place by getting a court order blocking it due to the possibility of violence. Regardless of a local chapter, many Bloomington residents were reportedly members of the terrorist organization at the time.

In April, Indiana University conducted a memorial service for the recently assassinated Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; no Black students were chosen to speak at the event. In May, after repeated demands that local fraternity chapters strike discriminatory clauses from their by-laws, local Black student leaders led 50 students a sit-in protest aimed at delaying the Little 500 race.

As African American students at IU tried to find ways to nurse their own community, their efforts were either intensely monitored and sometimes subverted by outside agencies. The Afro-Afro-American Student Association (AAASA), one of the first Black organizations at IU, formed in the spring of 1968. In June of that year, the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Indianapolis office included Bloomington's AAASA in a "new left movement" watch list, a fact revealed in a later-released memorandum.

In the memo, the Indianapolis office notes it has "exhausted every avenue that could effectively expose, disrupt and neutralize the activists of the various new left movement organizations, their leadership and adherents."

Black History Month:Catch up on this series

"The Indianapolis Office is well aware that it is imperative that the activities of these groups be followed on a continuous basis so the Bureau can take advantage of all opportunities for counterintelligence and also inspire action in instances where circumstances warrant," the memo describes.

Throughout this time, IU graduate student Clarence "Rollo" Turner was often at the center of fighting civil injustice. The Black IU student population hovered around 2% on the Bloomington campus. Turner was one of a few African American leaders who directly fought for community change, with actions such as co-founding the AAASA and helping to organize a protest at the Little 500 bicycle race.

Bloomington Black Market was a marketplace of culture and ideas

With the help and financial backing of some IU staff and students, Turner founded the Black Market in late September 1968 at the the northeast corner of Dunn Street and Kirkwood Avenue. Serving as a social center and cultural marketplace, the Black Market offered books, clothing, records, artwork and other crafts made in Africa or by African Americans.

"Turner envisioned the store less as a profit-making enterprise and more as a gathering place for students who did not have a place that was uniquely for them," an IU Archives exhibit noted.

The market was described as an immediate success by local publications at the time, though there was some community backlash. Spectator, a short-lived IU student newspaper, noted Black students involved with the market routinely faced abuse and harassment from white patrons. Prior to the events of late December, Larry Canada, a local businessman and antiwar activist who owned the land, said he had been receiving telephoned bomb threats due to his part in facilitating the market space.

The violent vandalism arrived in the early morning hours the day after Christmas, Dec. 26. Eyewitnesses reported seeing a trenchcoated white man launch a lit Molotov cocktail through the market's window before speeding away in a car. Though it would take nearly a year to identify the assailant, it was clear that the crime was racially motivated. The Black Market was the only business on the busy street corner attacked.

The bombing, as well as the subsequent apathy from first responders and mainstream media coverage, caused community tensions to reach a new peak. Turner held a rally outside the shop's charred shell in early January, where a sign reading "A COWARD DID THIS" hung across the shop's smashed doorway. Turner and students called for action from both the university and city for better protection from racially targeted violence.

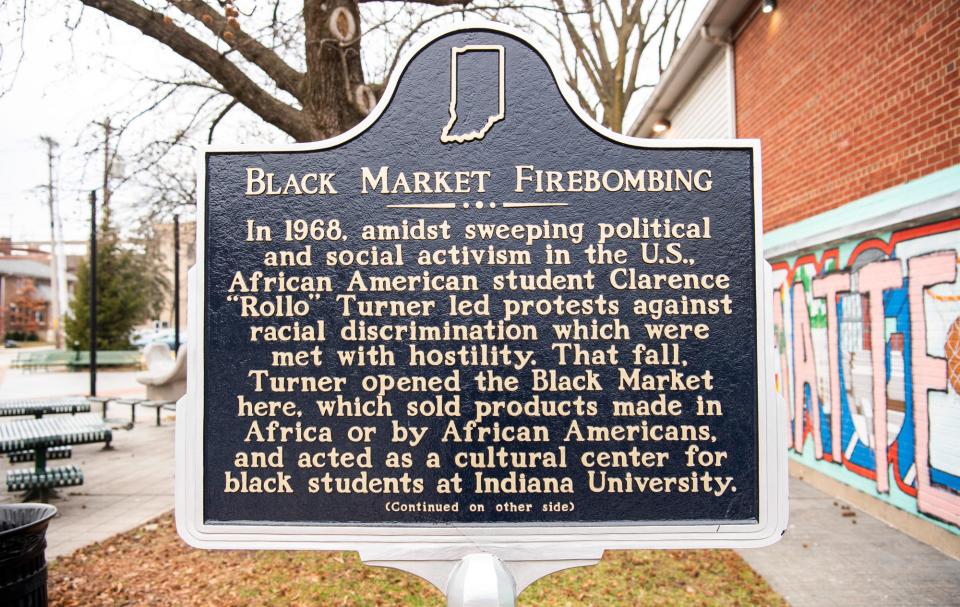

In 1969, two men with strong Klu Klux Klan ties were charged in connection to the fire-bombing. Carlisle Briscoe Jr. pleaded guilty and was convicted of second-degree arson. Charges against Jackie Dale Kinser, who Briscoe implicated as driving the getaway car, eventually were dropped, according to the Indiana Historical Bureau.

Turner was hesitant to reopen the store, saying he planned to leave Indiana the following summer. Community fundraising efforts helped pay back investors for the lost inventory and damaged infrastructure and the market never reopened. The building was razed, leaving an empty plot of land. Some students cared for the property, planting an array of flowers and vegetation.

After graduation, Turner became one of the founding faculty members of University of Pittsburgh's Black studies department. He would later spearhead efforts to make Black history more accepted into mainstream academia. The Canada family retained ownership of the land where the Black Market once stood. In the 1970s, it was donated to the city with the condition that it would always remain a park.

The property is now Peoples Park, named after the park at the University of California-Berkeley at the center of a controversy when a demonstrator was killed by police in 1969. Now, the downtown park features a state plaque of historic distinction sharing the history of the Black Market.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Bloomington Black business targeted by firebomb in 1968