DNA match gives family of deceased WWII airman closure

Staff Sgt. Franklin P. Hall is coming home.

The remains of the World War II airman, who was unaccounted for since 1944, were identified in July, thanks to a DNA match provided by his nephews. Beyers Funeral Home will be receiving his body on Dec. 15, and he will be buried in Lone Oak Cemetery on Jan. 21, according to his family.

“I never knew him,” said Jeff Hester of East Lake Weir. “He died before I was born.” However, he and his brother Judd played a key role in his identification. They both furnished DNA that matched their uncle.

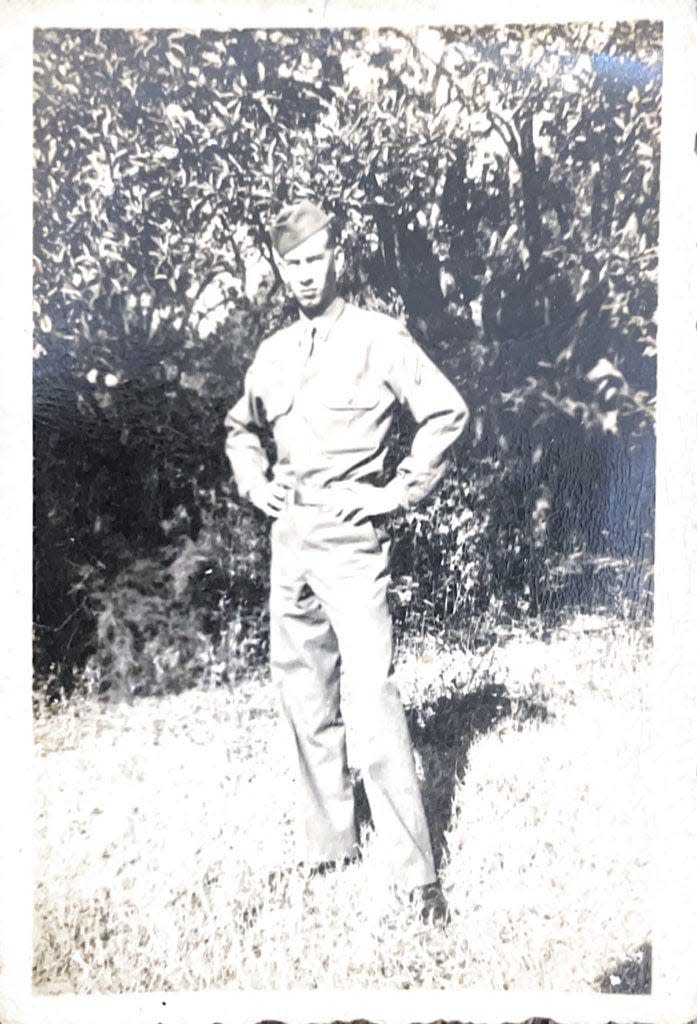

Looking at Hall’s photo, Hester said he could see the family resemblance in his mother and in his uncle, Milton. Milton, who was in the Army, was wounded. Hall’s other brother, Robert, also served in the military during the war.

Hall was just 21 when he died.

He was one of three brothers of his mother, Mary Julia Hester, who died in the 1990s, never knowing if he would ever be identified. “She hoped so,” Hester said.

Distinguished service

Born in Coleman, Hall grew up in Emeralda Island area outside of Lisbon, northeast of Leesburg.

Hall was assigned to the 66th Bombardment Squadron, 44th Bombardment Group (Heavy) in January of 1944. On Jan. 21, Hall, a left waist gunner onboard the B-24D Liberator Queen Marlene, was killed when his plane was attacked by German air forces near Équennes-Éramecourt, France, according to a news release from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA.)

German forces recovered nine sets of remains, which were interred in a French cemetery at Poix-de-Picardie.

The tail gunner, who parachuted, was the only one who survived, Hester learned. The military has still not accounted for the pilot and copilot.

Allied air forces were bombing rail lines, bridges and other key targets in preparation for the June 6 D-Day invasion at Normandy. Key among the goals was to draw out German fighter planes and destroy them with allied fighters.

“So great was our superiority in the air that all the enemy could put up during daylight over the invasion beaches was a mere hundred sorties,” former English Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote in his book “Triumph and Tragedy.”

Hall and his crew were on a specific, crucial mission when they were shot down. London was being terrorized by V-1 rockets, and they were ordered to find and destroy a launch site in northern France.

The four-engine Liberator was produced in greater numbers than any other American combat plane during World War II.

The search for Hall's remains

Beginning in 1945, the American Graves Registration Command searched the area around Équennes-Éramecourt, but Hall’s case was declared non-recoverable in 1951, according to the news release.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency later tracked down the possible remains at the Normandy American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site. Hester was contacted and he and his brother furnished DNA samples. The remains were sent to a lab, where the results were confirmed.

Hall’s name is recorded on the Tablets of the Missing at Ardennes American Cemetery, France, along with others still missing from WWII. A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

“It’s just very cool. It’s a fulfilment that others didn’t get to have,” Hester said. “My mother never got closure.”

He will be buried with military honors and escorted from the airport in Orlando airport to Leesburg. Some details are still being ironed out.

He was awarded the Purple Heart, Air Medal, and World War II Medal, according to military websites.

This article originally appeared on Ocala Star-Banner: DNA match gives family of deceased WWII airman closure