Remember phonics? It's back in style as NJ schools fight pandemic learning loss

“Sss-ah-khhh.”

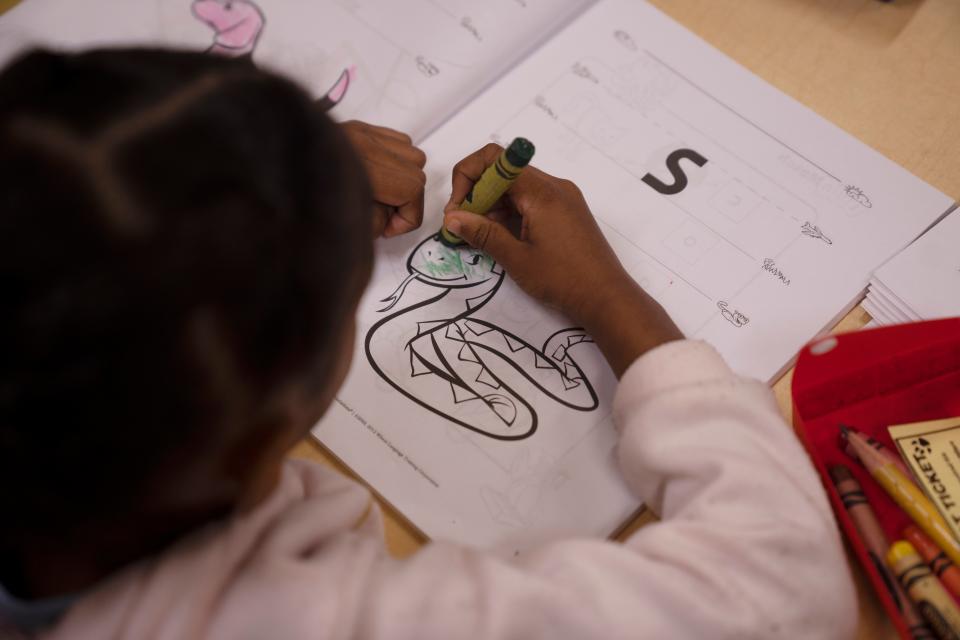

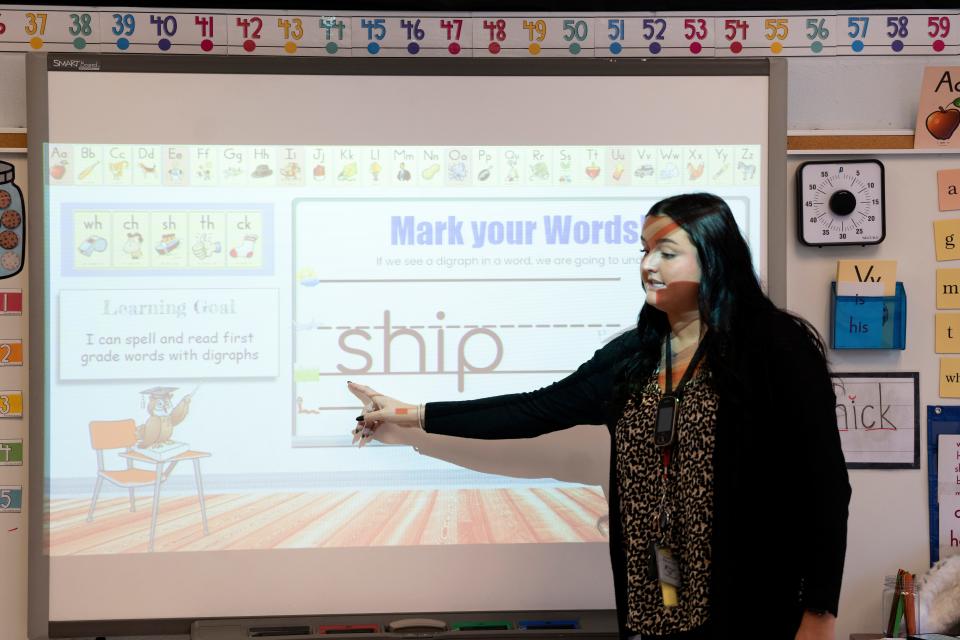

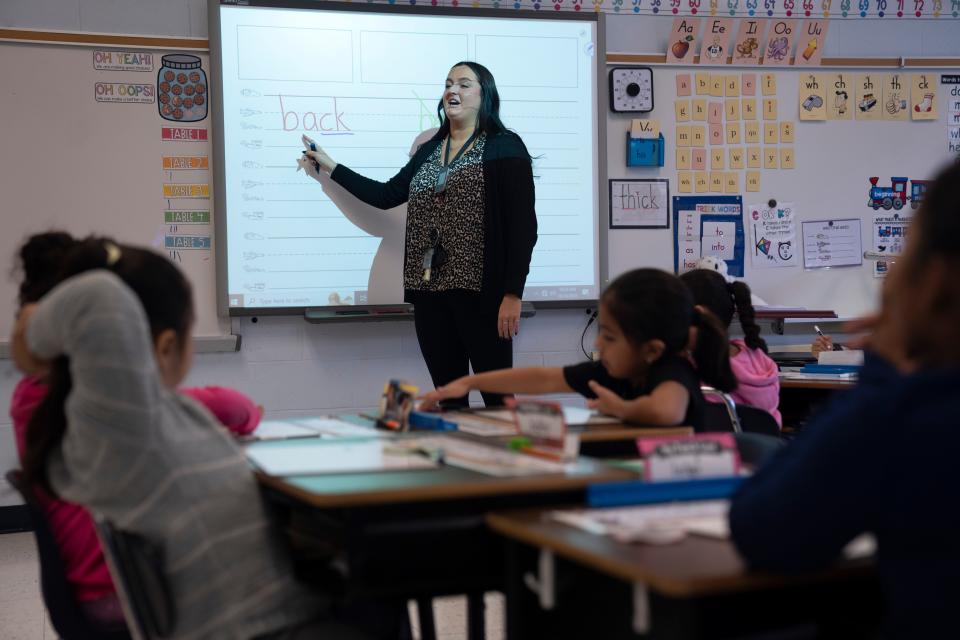

That sound recently filled the classroom of teacher Keely Hassert's first grade classroom at Clifton School 17.

Hassert's students were breaking the word "sock" into its three main sounds.

“What about ‘back?’ I hurt my back,” Hassert said, pretending to wince. “Why not spell it as 'bac'?"

“Because ‘ck’ falls behind the short vowel sound,” her students chanted back.

Hassert then had the kids watch her mouth for the "th" in “thin.”

Foundational skills for early readers are back under the microscope after the COVID-19 pandemic showed that something was missing from the way children learned to read.

During the pandemic, when 6- and 7-year-olds had to wear masks during their lessons, much of the sounding-out, the facial expressions and the signs of encouragement were lost.

In 2019, 42% of fourth graders in New Jersey were proficient in English, but in 2022 that number had dropped to 38%, according to an analysis of national data provided by FutureEd, a K-12 think tank.

The latest and widely embraced solution to address this drop in reading skills is to have teachers use the Science of Reading approach, emphasizing letter-sound connections and other reading pillars like vocabulary, fluency and comprehension.

The program is designed to help kids decode words on a page without using context cues or pictures, and experts welcomed its foundational approach after it was promoted in a report issued by the National Reading Panel in 2000.

Revising standards to address lost reading proficiency

States have rushed to pass laws related to the pandemic’s learning losses. New York City announced that its schools would adopt Science of Reading curricula this academic year.

New Jersey revised its own English language arts standards in October, incorporating elements of Science of Reading, said JerseyCAN, a K-12 advocacy group that has campaigned for reading reform in the state.

Though New Jersey continued to rank higher than the national average in fourth grade reading skills after the pandemic, a deeper look at the numbers shows problems that can be overlooked because of the success of the state’s many affluent small districts.

Elementary schoolers in Paterson were trailing the state in 2022 scores, with 15.4% of third graders reading at or above proficiency, compared with 83.7% in Millburn, a recent JerseyCAN report showed.

But even in wealthy Millburn, in Essex County, Black students lag well behind others in reading proficiency. In 2022, 95.7% of Asian third graders and 75% of white students in Millburn were proficient in reading, compared with 30.8% of Black third graders.

So the changed English language standards were “a positive, critical step,” JerseyCAN Executive Director Paula White said in a statement last month.

"Drawing attention back to the structure of the English language is the right thing to do for kids," White said.

"Without a strong grasp of how to apply decoding skills to texts, many students will never know the joy of curling up with a book about their own heritage or their favorite hobby, nor will they be able to access content in subject areas that serve as a gateway to various professions and trades,” she said.

New Jersey’s revised standards “are focusing a lot more on the foundational reading and foundational writing skills,” said Josephine Solorzano, the K-8 English language supervisor in the North Bergen School District.

This is a key change, she said. The “whole language” approach of the 1970s and '80s — gauging the word by looking at it instead of breaking it down — stops working in higher grades, when kids read more complex material.

“Students really can't advance grades until they have got a good foundation,” Solorzano said.

Renewed focus on reading after pandemic

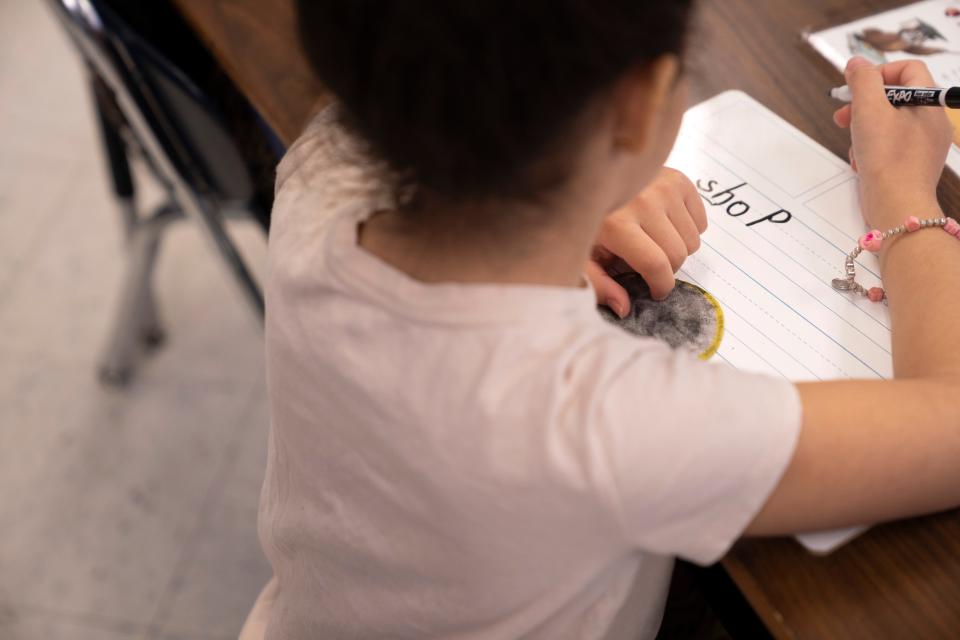

In Clifton and North Bergen, elementary English teachers use a “balanced literacy” approach, prevalent since the '90s, that balances phonics with fostering a love of reading and story. Both districts use Wilson’s Fundations, a curriculum for early-grade literacy grounded in Science of Reading techniques.

But the renewed focus on reading grew from alarming reports about third and fourth graders lagging in reading after the pandemic.

“The younger children struggled with writing and communication ... because they were all kind of in their own little island” during the pandemic, said Valerie Kropinack, the K-8 language arts supervisor for Clifton Public Schools.

Yet since even before it became a buzzword in education, Clifton and other districts have used Science of Reading approaches, said Janina Kusielewicz, Clifton's assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction.

“Science of Reading, whole language, phonics, are all the labels,” Kusielewicz said. “But you need the whole gamut. You need the pieces to learn how to decode" and "to learn how the sounds come together."

"But then you build that into a fluency model, and layer on comprehension," she said. "So reading is a whole process. Each of these buzzwords is just a little piece of it.”

Teacher training is critical

In Clifton, kids went home during the pandemic with “leveled” reading books in little Ziplocs. Each child got a set of letters to tap out sounds for multi-sensory reading skills, even before they got computers for online learning, Kusielewicz said.

But when fourth graders returned to school after missing a year and a half of normal school, many teachers found themselves struggling to teach foundational reading skills that the children had not developed in earlier grades. Newer standards aren’t enough; teacher training is critical, said Solorzano and the other educators.

“Fourth grade teachers might say: How do I fix it? I don't know the rules of phonics. I don't know how to teach them to break a word,” Solorzano said.

Clifton has two literacy coaches on its staff who conduct regular study groups for teachers, as part of the district’s model of “embedded” professional development. In October, it held Fundations training for staff.

North Bergen opened its school year with a talk on the Science of Reading for teachers and additional training for third and fourth grade faculty. “That's where we see the gap. That's where we have to close it,” Solorzano said.

The new state standards are “phenomenal in breaking it down and bringing value to the foundational skills,” Solorzano said. “But it's the delivery — developing teachers — that we all need to work on.” Many older faculty members are not trained in teaching phonics-based classes.

Wide gaps remain

Forty-two states passed reading reform laws covering students from kindergarten to beyond third grade between 2019 and 2022, according to the Albert Shanker Institute, a nonpartisan Washington-based think tank. New Jersey is one of just five states that did not pass any laws.

The state Department of Education’s English language standards page does not specify Science of Reading techniques, but JerseyCANs White said the state answered her group’s call to fold it into its revisions. More needs to be done, she said.

Some of these standards — which cover teacher training, screening kids for literacy needs when they enter a grade and requiring school boards to adopt curricula — may not be easily adapted to the state’s framework of local control. Last week, the state announced $41 million in high-impact tutoring grants to school districts to accelerate learning and bridge the pandemic's gaps.

But wide gaps exist between high-performing and marginalized student groups who face income barriers or lack family and background exposure to books and language, another foundational aspect of early literacy brought out in studies.

These "achievement gulfs," said the JerseyCAN report, are hidden "below the surface" in high-performing districts and should not “lull residents into a sense of complacency that things are fine for all students in their schools.”

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NJ schools bringing back phonics to fight COVID learning loss