Remembering Achsa Bean, early UR medical grad and pioneering military doctor

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

How could Achsa Bean have proven herself any further?

She hid in British bunkers and subway tunnels from Nazi air attacks, then helped dig casualties out of the rubble. She worked tirelessly in a rural field hospital during heavy fighting, supervising the care of entire wards full of maimed soldiers as well as civilian women and children. She earned a promotion to the rank of major on the strength of her fellow doctors’ recommendation and recruited fellow women to enlist alongside her in the British Royal Army Medical Corps.

Now, in the fall of 1942, she was back in Poughkeepsie, on leave to resume her teaching duties at Vassar College. People kept asking whether she thought women could succeed alongside men as commissioned doctors in the U.S. military.

A ridiculous question.

“I certainly am no feminist,” she said. “But it seems only right that the great demand for doctors should be filled by the most qualified, regardless of whether they are men or women.”

When the U.S. Congress finally agreed to commission female doctors in 1943, Bean, a 1936 graduate of the University of Rochester School of Medicine, was one of the first. She was an obvious choice; her valiant volunteer service for England had been an embarrassment for her American medical peers who argued against gender equity in enlistment.

Bean died in her native Maine in 1975, accompanied as always by her life partner and fellow physician, Barbara Stimson.

Nearly 50 years later, Bean is largely forgotten, both in Rochester, where she was a rare early female medical school graduate and faculty member, and in Poughkeepsie, where she spent the majority of her career.

Bean among the earliest female graduates of UR medical school

The name Achsa is a biblical one. In the book of Joshua, a woman named Achsah is given in marriage as a reward for a military victory.

After the marriage, she requests and receives from her father some parcels of land with fresh water sources, since her new home is very dry. Achsah, therefore, is an example of a woman who demonstrates agency and attains property even within a highly patriarchal society.

Achsa Mabel Bean was born in 1900 in central Maine. Her father was a itinerant salesman with chronically poor health, and Bean worked several jobs — high school teacher, camp counselor, librarian — to pay her way through undergraduate and master's degrees in zoology at the University of Maine's Orono campus.

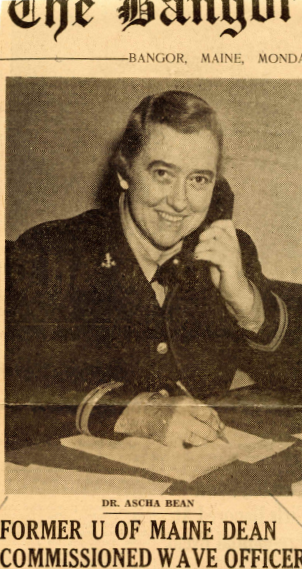

She spent six years as dean of women at the Orono campus and studied briefly at Radcliffe College, then the female affiliate of Harvard University, before moving to Rochester in 1933 to enroll in the University of Rochester School of Medicine.

She earned her medical degree in 1936 — one of three women in a class of 40 — and spent the next two years as an internist in obstetrics and gynecology.

By 1938 Bean's father had died, and she was the main support for her mother and grandmother. Seeking a pay raise, she took a faculty position at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie.

It was while at Vassar that she met Barbara Stimson, a physician at Columbia University who would become her lifelong professional and personal companion.

Stimson was a Vassar graduate and a celebrated expert in orthopedic surgery. She was also first cousins with Henry Stimson, the U.S. secretary of State.

When World War II began, both women felt compelled to serve. They traveled to England and joined the British Medical Service as civilian doctors. They were guests at the home of Waldorf Astor and Nancy Astor, the first female British member of Parliament, when Pearl Harbor was bombed.

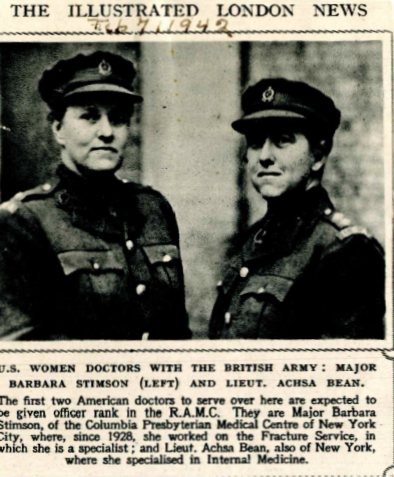

At the time, the United States did not commission female doctors, fearing they'd become squeamish in a war zone and that men would not take orders from them. Instead, Stimson and Bean joined the British Royal Army Medical Corps, Stimson as a major and Bean as a captain.

“It seemed impossible for anyone to avoid the war, and the sooner I could do something, the happier I would be,” Bean told a journalist in September 1942.

'The same standing and respect'

Both women served with distinction in war hospitals. They got used to being addressed as "sir" — a bit of military protocol that proved inescapable — and worked side-by-side with their male colleagues under intense pressure.

Their first test came quickly, when their ship across the Atlantic Ocean was attacked by a submarine. Bean often told a story about the time she was just about to take a long-hoped-for bath at her apartment in London, only for the building to be hit by a bomb as she was filling the tub.

Despite her gender, Bean looked the part of a wartime officer, according to a memorial minute from her Vassar colleagues.

"She was built on a large scale and had a voice that could match it," they wrote. "She was impressive, not to say intimidating, without the uniform; with it, she must have seemed like a dreadnought."

In a letter to her mother in February 1942, Bean described her and Stimson's shock the first time Stimson, technically her superior, received a formal salute from a male soldier.

"We met a private who saluted smartly and Barbara recovered from her astonishment quickly enough to acknowledge it but in a good bit of confusion," she wrote. "I turned my eyes to look at her and saw a bright scarlet mounting rapidly from the collar line. We had a grand laugh over it later."

Bean returned to the United States in September 1942, in part to help care for her mother. By then it had become a sore point for the U.S. to have its own female citizens serving in a foreign military, and Stimson pressed the case directly with her cousin, the secretary of state.

As Bean put it: "(Female military physicians) do not faint; they do not misbehave. ... They are seasoned doctors and they know their work."

In April 1943, Congress passed the Sparkman Johnson Act, allowing women to receive temporary military commissions. Bean became a lieutenant in the Naval Medical Corps, among the first women to do so. She served at Navy medical facilities in Maryland, New York City and Pearl Harbor and received a promotion to lieutenant commander before the war ended.

She returned to Vassar after the war and remained there until 1963, serving as professor of hygiene and lecturing often about health care and public service.

"She was a fearless woman, not afraid to tackle anything," her Vassar colleagues recalled. "She inherited ideas of loyalty and service and she gave her life to furthering them."

'Cream of the crop'

After retiring, Bean moved to Owls Head, Maine, where she had designed her own oceanfront home. She was joined by Stimson, who since they first met in 1938 had become more than a professional acquaintance.

Stimson had followed Bean to Vassar shortly after the war ended. They worked and lived together for nearly 40 years, and though they never said so publicly, people who knew them confirmed it was a romantic relationship, not simply a friendship as the newspapers at the time reported.

"That was the consensus," said Rodney Weeks, whose grandmother was close friends with Bean and Stimson in their retirement in Maine.

That makes another hidden fact all the more surprising: Bean, who spent her adult life in a committed same-sex relationship, had a son. He was born in August 1929, when Bean was studying at Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She gave him up for adoption to a nearby family and kept the relationship a closely guarded secret for the rest of her life.

"You can imagine it was confusing for me as well," said Deirdre Hendrie. She is the widow of Bean's son, Gordon Hendrie, who died eight years ago.

Gordon Hendrie did not know about his mother until he was 16 years old, but after that, they developed a fairly close relationship, Deirdre Hendrie said, though Bean did not discuss it outside her own family.

The Hendries spent most of their life in British Columbia, Canada, where Deirdre Hendrie still lives. Bean and Stimson kept up a relationship with them and with Bean's three grandchildren, visiting each other periodically in Maine or Canada.

Bean's obituary contained no mention of a son or grandchildren. In their wills, though she and Stimson left the Owls Head property to Gordon Hendrie.

"She was a very nice woman, but it was sort of on her own terms," Deirdre Hendrie said. "Of course, she'd been so independent for so long." She recalled Bean and Stimson giving her a physical examination before the marriage to make sure she was in good health.

Weeks, now the secretary of the Mussel Ridge Historical Society in Owls Head, Maine, recalled Bean's deep, raspy voice — she was a talented singer before cigarette smoking spoiled her vocal cords — but also the way she and Stimson, two highly educated doctors who'd lived in major cities, stood out in rural Maine.

"The area was kind of backward at the time — people were using outhouses and stuff," Weeks said. "So when educated people came around, that was a big deal. They were really the cream of the crop. ... And for a 10-year-old boy, she was just a sweetheart."

Carolyn Philbrook, the historical society's vice president, sometimes went with her grandmother to clean the women's house or to watch their dogs, a pair of Norwegian elkhounds named Gunda and Jarda. Bean sometimes took her for a ride in her bright blue Mercedes.

"She was very obliging, very down-to-earth — just helpful," Philbrook said. "If I had an ailment, my mother would take me down to see if Dr. Bean could say what was wrong. ... They fit into the community real well."

Achsa Bean died in March 1975 and was buried in Maine. Stimson lived until 1986.

After World War II, Bean often gave lectures about public health and her experiences in the military. She never failed to mention some of her basic principles: the virtue of service to one's community and country, and the importance of equal opportunity.

"In English hospitals which were filled exclusively with soldiers, women doctors worked by the side of men and had the same standing and respect as any of the male contingent," Bean said in one speech upon her return. "They stand up in emergencies just as the ordinary women civilian shows courage in a bombing. It's the individual's qualities which count."

Contact staff writer Justin Murphy at jmurphy7@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Remembering Achsa Bean, early UR medical grad and pioneering military doctor