Remembering when Billie Jean King made history in Phoenix 50 years ago

Billie Jean King invested almost half a decade into the research and writing of her recently published autobiography, “All In,” a 420-page opus that reached almost twice that length before editing.

“We had to get it down, there’s so much I wish I could have put in,” says King, who partnered with Johnette Howard and Maryanne Vollers on the writing and credits Helen Russell for a lead research role. “But I think this is the essence, which is what you’re trying to get to.”

Getting to the heart of any issue is what King, who turned 78 on Monday, has always aspired to find. When she was 11 in the spring of 1955 and playing for the first time at the Los Angeles Tennis Club, King was not allowed in a junior group photo because she was wearing shorts instead of a dress or skirt.

“I had already played plenty of other sports wearing shorts,” she writes. “I had already played plenty of other sports and never had an adult act like this. So why was tennis so unwelcoming?”

Her causes grew exponentially along with her tennis career, stretching in singles from 1959 (when she made the first of 51 Grand Slam appearances) to 1983 and even longer in doubles. Her straight-set defeat of Bobby Riggs in a 1973 best-of-five "Battle of the Sexes" match remains a central moment in the early Title IX era and broader gender equality movement.

“Suddenly I was catapulted to the forefront of social justice movements that were effecting great change,” King writes. “I found myself with influence that leaped the firewall of sports and spread into the worlds of entertainment, business and politics.

“In the five decades since, it is not an exaggeration to say not a day has gone by without someone talking to me about the Battle of the Sexes match. Women still tell me about where they were when they saw it, how happy and empowered they felt when I won.”

It’s also not exaggerating to say no one in athletics has done more than King, founder of the influential Women’s Sports Foundation in 1974, to help level the playing field for women in a myriad of ways, including earnings, media coverage and LBGTQ+ rights.

Lengthy Arizona connection

It’s late September. “All In” has been available for more than a month, debuting at No. 5 on the New York Times best-seller list. King knows promotion work is never finished. She’s on the phone for a scheduled 30-minute interview that she willingly extends to almost twice that length.

“I have nothing but great memories about Arizona,” King says. “My mother and dad loved Prescott. They had more friends and went dancing at the (now closed) Pine Cone. I could do a book just on Arizona.”

Bill and Betty Moffitt moved in 1987 from Long Beach, California, where Billie Jean grew up, to Prescott, also where her younger brother Randy (a former major league pitcher) lived for many years. Bill died in 2006 and Betty in 2014.

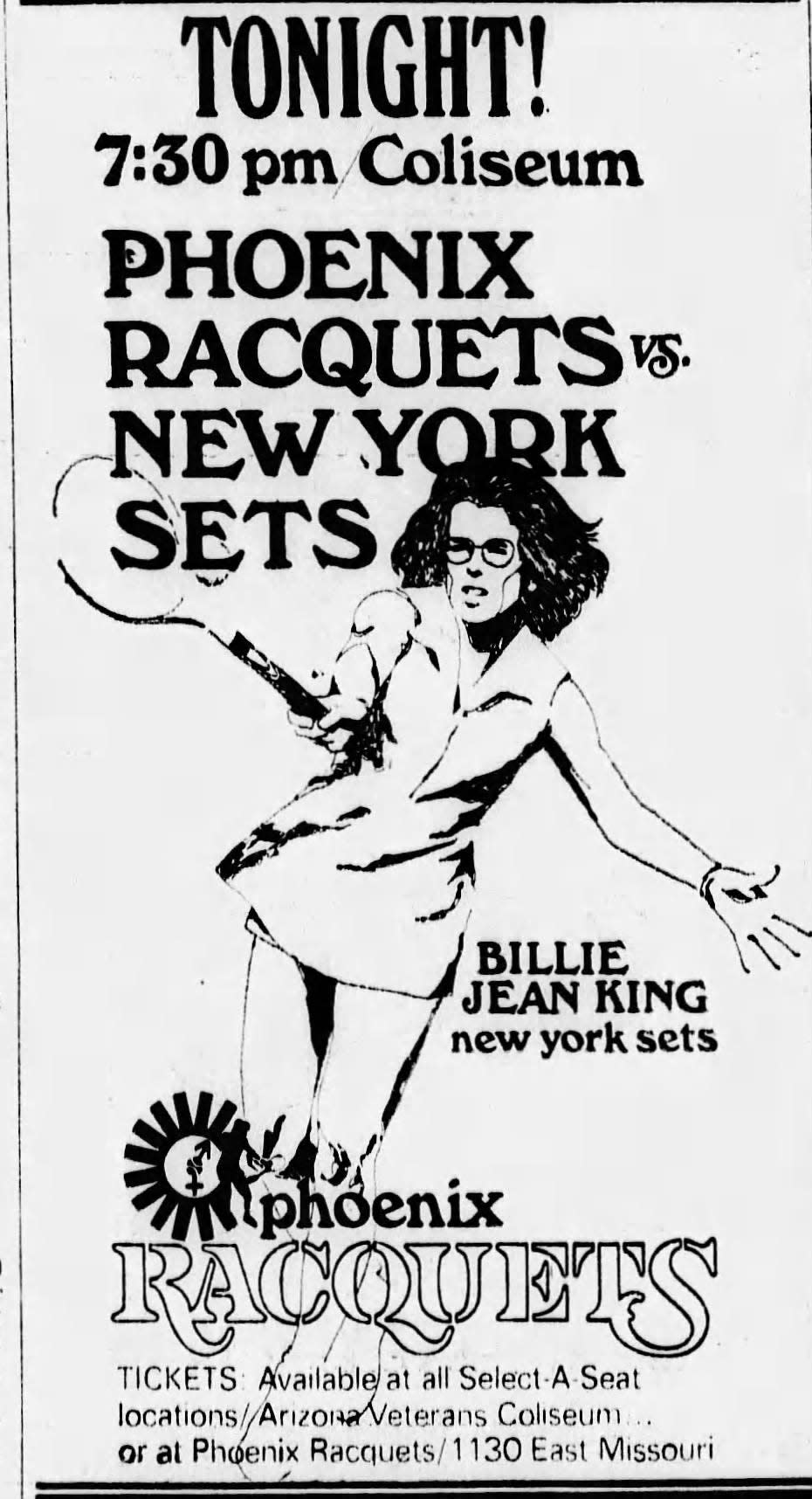

King’s playing career in Arizona runs from at least 1966, when she won the Thunderbird Invitational at Phoenix Country Club, to 1977, when she was World Team Tennis female playoff MVP for the New York Apples in their championship win over the Phoenix Racquets at Veterans Memorial Coliseum (a Racquets record 11,294 attended the series finale).

But what King completed in Phoenix in 1971 still, a half century later, ranks among her greatest accomplishments because of the larger context surrounding her becoming the first female athlete to earn $100,000 in a single year.

Because of an ongoing disparity in men’s and women’s prize money, and in particular an 8-to-1 ratio at the 1970 Pacific Southwest Championships, World Tennis magazine founder Gladys Heldman organized a women’s only tournament in Houston for the same week. The U.S. Tennis Association threatened to suspend any participating players, but a group including King — now known as the Original Nine — signed $1 contracts with Heldman, in essence betting on themselves and their earning potential.

“The three things we were willing to give up our careers for, for the next generation, was that any girl born in the world would finally have a place to compete,” King says. “And to be appreciated for our accomplishments, not only our looks, and to be able to make a living because our generation came from amateurism when we made $14 a day.

“We knew we might never get to play again, and we just said let’s go for it. If we hadn’t had male allies, we wouldn’t have made it. People have to realize what’s possible working together.”

What came out of the breakaway success in Houston was the Virginia Slims women’s tour and in 1973 the Women’s Tennis Association.

There were 19 Virginia Slims tournaments in 1971 plus others sponsored by the International Tennis Federation, some non-tour events and the four Grand Slams.

King set a goal in January of surpassing $100K in earnings, equivalent to $677,000 today, then reeled off five straight Virginia Slims titles to start the year. But getting to the historic finish line wouldn’t be easy.

Facing decision on pregnancy

In late February 1971, King won again at a Virginia Slims stop in Boston where she also became pregnant.

“I knew it almost immediately,” she writes. “I had stopped taking birth control pills after Larry showed me a magazine article that said it was dangerous to stay on them for more than five years. Maybe it was just more magical thinking on my part, if I was thinking at all.”

Billie Jean and her then husband, Larry King, wanted to have children, but not when she was 27 and in the prime of her career (winning nine of her 12 Grand Slam singles titles from 1966-72).

“Our marriage was too shaky, and our lives were so complicated and unpredictable,” King writes. “Also, I now realized my attraction to women wasn’t going away. I didn’t know what I wanted, and I didn’t know what Larry and I were doing.”

King chose to have an abortion, when she was five weeks pregnant, a seminal moment two years before the U.S. Supreme Court's Roe vs. Wade decision legalizing abortion in the first trimester.

Before a woman could have an abortion in California in 1971, she was required to appear before a medical committee to explain the decision, something King calls the “most degrading thing I’ve ever experienced.”

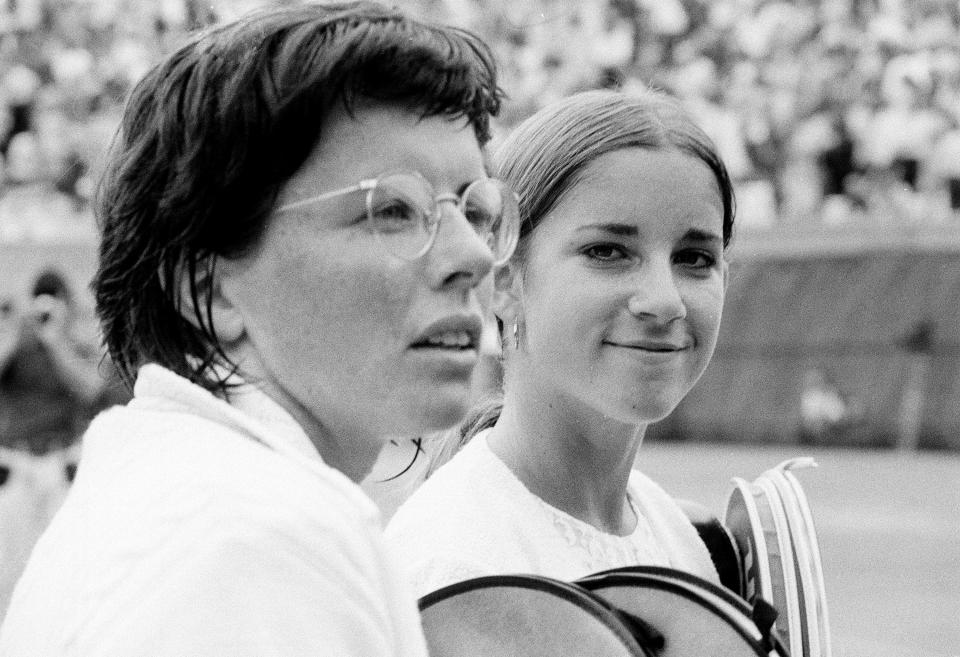

Heldman and others convinced King, just three days after her abortion, to play at a tournament in St. Petersburg, Florida, where she faced Chris Evert, then 16, for the first time. “It was foolish, I know,” King writes. “It was yet another of those times I shouldn’t have played, but I was driven to make the tour succeed.”

She and Evert split the first two sets of their semifinal before King “feeling so sick from the heat and from cramps,” she writes, forfeited.

“Gloria Steinham has this correct,” King says of the renewed debate about abortion rights. “When a country is right, every woman has a right to reproductive self. Until we get that right, we’re not a full citizen. A woman should decide about her own body like a male should decide with his body. The generation today are having to deal with this again. I know what it feels like before Roe vs. Wade, and it was ridiculous.”

Reaching $100K milestone in Phoenix

Progressing into the summer, King skipped the French Open, lost to Evonne Goolagong in the Wimbledon singles semifinals then beat Evert, 6-3, 6-2, on the way to her second of four U.S. Open singles titles. She won $5,000 (compared to $15,000 for men’s champion Stan Smith), keeping her $100K pursuit alive.

King won a Virginia Slims stop in Louisville then gave away some earnings at the Pacific Southwest Championships when she and Rosie Casals defaulted at 6-6 in the first set of their singles final to protest what Casals later described to The Arizona Republic as “atrocious (line) calls.”

“I told Rosie to stay on the court and get the win,” King says. “Jack (Kramer) went ballistic, rightly so — it was his tournament. My brother, who was hardly ever at a tournament, almost decked Jack. But I was wrong, I made a mistake.”

So it was on to Phoenix Tennis Center for the Virginia Slims finale with King needing a win to cross the $100K barrier in a year when the top paid major league baseball players made under $200,000.

King kept the drama to a minimum, winning five singles matches in straight sets, the closest 6-4, 7-5 over Kerry Melville in the semifinals. Her 7-5, 6-1 finals win over Casals clinched her 11th title on the Virginia Slims tour.

“What a great day that was,” King says. “I remember the Levines (Bill and Ina) had a party for us over at their house. They had a cake that said 100,000 on it and had my (wire rim) glasses I loved to wear in those days. It was so sweet.”

She won one more international tournament in 1971, finishing with $117,000 for the year. By comparison, Australia’s Ashleigh Barty is the leading money winner in 2021 at just under $4 million

A day after the Phoenix tournament, on Oct. 4, King was in New York for a Philip Morris-sponsored press conference that included a congratulatory phone call from President Richard Nixon.

“It meant a lot to me,” says King, whose father had a basketball scholarship to Whittier College, the school Nixon attended. “It’s great they made a big deal of it because why do it if you’re not going to tell the world. It helped put us on the map.

“Sometimes how you start is how you finish. It got us started right, and women’s tennis has always been the leader in women’s sports because of those moments.”

Billie Jean King Arizona finals

Singles

1966: def. Mary Ann Eisel, 6-3, 6-2

1971: def. Rosie Casals, 7-5, 6-1

1972: def. Margaret Court, 7-6, 6-3

1973: def. Nancy Richey Gunter, 6-1, 6-3

1977: def. Wendy Turnbull, 1-6, 6-1, 6-0

Doubles

1966: King-Mary Ann Eisel def. Victoria Palmer Heinicke-Kathy Harter, 6-1, 6-4

1971: King-Rosie Casals def. Francoise Durr-Judy Tegart Dalton, 6-3, 6-2

1973: Kerry Harris-Kerry Melville def. King-Casals, 6-4, 6-4

1976: King-Betty Stove def. Linky Boshoff-Ilana Kloss, 6-2, 6-1

1977: King-Martina Navratilova def. Helen Gourlay Cawley-JoAnne Russell, 6-1, 7-5

Support local journalism: Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Remembering when Billie Jean King made history in Phoenix 50 years ago