Remembering a Black Boone County teenager who was lynched at the old courthouse in 1889

On Sept. 7, 1889, Black Boone County teenager George Bush was forcibly taken from the Boone County Jail by a mob of white men.

Bush was marched to the then-Boone County Courthouse, whose columns still stand, and was hanged from a second-story railing outside of a window.

This was the second confirmed lynching in Boone County history.

The incident was recognized and commemorated in a ceremony Wednesday at the amphitheater of the courthouse square.

The Community Remembrance Project of Boone County aims to keep the past present, said Brad Boyd-Kennedy, with the organization, of the reason behind hosting the event. The local project is part of the Equal Justice Initiative of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice as well as the Legacy Museum.

"These (lynchings) were a product of white supremacy and control of the Black and indigenous population, which was prevalent in the years after reconstruction and leading to and up through the Jim Crow era," Boyd-Kennedy said. "... There is a very deep connection between the society of 133 years ago and the society today."

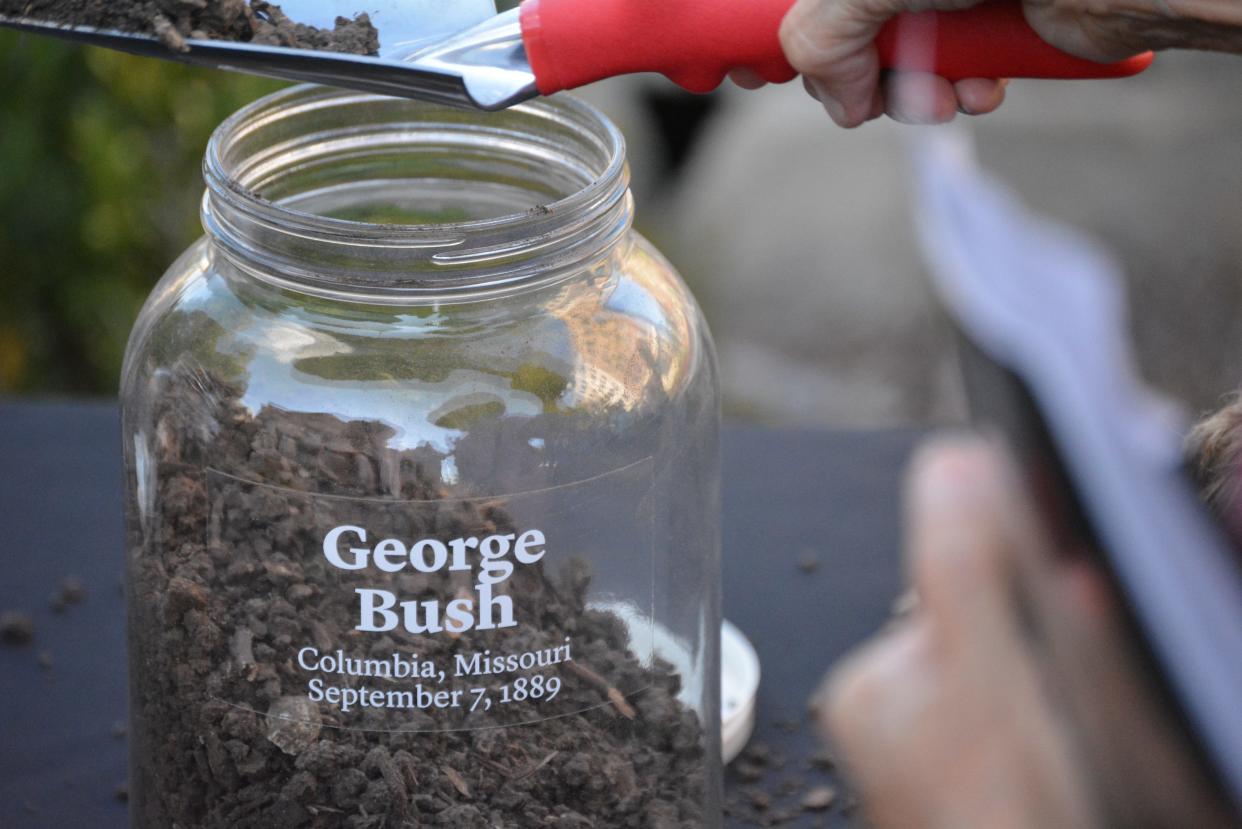

Soil gathered from near where Bush died was placed into three jars. The first will join the soil collection at the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama; the second will be displayed at the Boone County Government Center; and the third will be displayed at the Black Archives of Mid-Missouri in Kansas City.

The jar staying in Boone County will join another that was filled last year in a similar ceremony recognizing the 1923 lynching of James T. Scott.

More: Columbia leaders remember James T. Scott, victim of the last recorded lynching in Boone County

The organization also is working to get more information about another formerly enslaved man named Lewis, lynched possibly in 1866 by a guerilla group that had been led by "Bloody Bill" Anderson, Boyd-Kennedy said.

Guests to Wednesday's event helped fill the three jars in a solemn ceremony, which provides a concrete acknowledgement of Bush's death, Boyd-Kennedy said.

The symbolic reason soil is collected is because it is what collected the sweat and blood of victims, along with the tears of those who have mourned.

The soil also presents an opportunity for new growth.

Keslie Spottsville, founding member of the Community Remembrance Project Missouri Coalition and board member of the Black Archives of Mid-America, delivered Wednesday's keynote address.

The guiding principles of soil collection are remembrance, reconciliation and repair, she said, addressing historic enslavement and post-emancipation laws that disproportionately affect Black residents with imprisonment.

"All of us have been affected by negative (racial messaging) whether we are conscious of it or not," she said.

Reconciliation is the most difficult process to confront and reckon with, Spottsville said.

"We have to reconcile although 4 million people were freed from bondage, they were given zero economic or emotional support for entering society," she said, adding disparities deepened through land being returned to former owners of enslaved people and homestead acts that benefited white citizens.

So how do you repair and make amends following a reconciliation of history?

"Collective understanding and increased self-awareness can enable us to produce both direct and nuanced remedies for systemic changes across all levels of society," Spottsville said. "These redress methods must be rooted in remedying the original problem: economic injustice based on the false construct of racial hierarchies."

Poet Gabriel Levi performed his piece titled "Strange" during the ceremony. The piece asked those present to not only learn the names and stories of Black heroes like Harriet Tubman, but also historic victims of injustice like Bush.

"Look back and question what you have been taught. Our loss matters as much as our heroes," Levi said.

Sharing the story

George Bush was only 17 or 18 years old when he was killed.

His killers put a sign on Bush's body for it not to be cut down before 7 a.m., while also warning that anyone who revealed the identity of the mob members would have the same fate as Bush. Law enforcement did not intervene to stop the lynching.

"It took place only a few yards from where the ceremony took place," Boyd-Kennedy said.

Columbia Mayor Barbara Buffaloe, Boone County Northern District Commissioner Janet Thompson and Columbia Third Ward council member Roy Lovelady all spoke during Wednesday's ceremony.

While much has changed since Bush's death, communities still see mob mentality and racial terror in the lives of community members, Buffaloe said.

"Understanding our past is important to changing our future. Having uncomfortable conversations will help us prevent the past from repeating itself," she said.

Thompson shared a story of her memories visiting family in Montgomery when she was younger and also of another local family who had to plan their route and stops very carefully because they were Black. This was Elliot and Muriel Battle.

She shed light on the county's Upward Mobility project, which aims to dismantle systemically racist policies in the county and implement a new system of diversity, equity and inclusion, Thompson said.

"It won't erase the horrors of the past," she said. "Projects such as upward economic mobility can raise public awareness, facilitate education and work toward reconciliation and a brighter and more enlightened future for everybody in our community."

Lovelady explored the "then" of the lynching and how it relates to today.

"Are we far away enough from our past?" he said. "... Imagine being taken out of the jail. Now imagine being taken out of your car.

"... Don't sit in silence when you have a voice that you can send up. You know the story (of Bush). Tell the story to a friend. History is being denied in schools. ... Let us not let our history be hidden."

Finding more stories

The Community Remembrance Project is one of several organizations associated with the Equal Justice Initiative, Boyd-Kennedy said.

While the Boone County chapter has done initial research through the Boone County History and Culture Center, the initiative also has a trove of research documents, including on Bush and Scott, Boyd-Kennedy added.

"We did some initial search and had that corroborated by primary sources, newspapers of the time," he said. "We haven't been able to find relatives of Mr. Bush. As far as we know, he didn't have children or was married because he only was 17."

Events are thoroughly documented, so there is no doubt Bush's lynching happened, Boyd-Kennedy said.

Charles Dunlap covers local government, community stories and other general subjects for the Tribune. You can reach him at cdunlap@columbiatribune.com or @CD_CDT on Twitter. Please consider subscribing to support vital local journalism.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Historic Boone County lynching commemorated with ceremony