Remembering Korea: West Texans made an impact as the war ramped up

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(This is part two of a three-part series marking the 70th anniversary of the Korean War. Look for part three in the Avalanche-Journal next week.)

By all appearances, by late fall 1950, it looked like the Korean War was going to be a quick and complete victory. As noted in last week’s article, The Chinese First Offensive at the battle of Onjong-Unsan proved that General McArthur’s talk of “being home by Christmas”, was just that, talk. The Chinese lost several thousand men after that first offensive. Not be deterred, Mao Zedong had thousands more “volunteers” ready to do battle. The Chinese learned from the first offensive to stay hidden during the daytime (especially from the U.S. Air Force flying daylight raids) and attack at night when the Eighth Army and X Corps were not prepared.

Encouraged by the success of the Chosin Reservoir, Mao continued to press his advantage. This was to be MacArthur’s biggest mistake of the war. Realizing the position they were in, the United Nations Command, or UNC, was forced into a fighting retreat back to Seoul, having to give up the recently captured North Korean capital, Pyongyang. For the rest of the war, the UNC fought to recapture ground surrendered. Help would soon be on the way.

With his battlefield wins and advances, Mao Zedong was bent on unifying all of Korea and drive the Americans and their “puppets” off the peninsula. He was even more excited when the Chinese retook Seoul when their Third Offensive was successful in retaking the city on Jan. 5, 1951. However, General Matthew Ridgeway was bolstered by the addition of UN nations such as Britain, Turkey, France, Belgium, Netherland, Greece, Colombia, Thailand, Ethiopia and others pushed back up to the Han River in late January 1951. There would be a Fourth and Fifth offensive as the two sides would be in a tug of war for control of the country with neither able to gain ground on the other.

As thousands more died, then President Harry S. Truman tired of General McArthur’s independence and doing things his way from his office in Tokyo atop the Dai Ichi Life Insurance Building. He had been in this building since the end of WWII in 1945. In the spring of Truman’s main concern was to save as many lives as possible and work for a ceasefire along the 38th parallel. MacArthur did not think this was a good idea. MacArthur had ignored direct orders from Truman numerous times. On April 11, 1951, the President officially relieved MacArthur of command. Lt. Gen. Matthew Ridgway became the new commander in chief of the UNC.

Both sides were suffering horrific losses by mid-June 1951. The Chinese-North Korean armies suffered 500,000 casualties and their Army now stood at over 1,000,000. The UNC numbered around 800,000 troop but stilled controlled the air war by doubling the number of aircraft from 700 in July 1950 to over 1400 by early 1951. Nearly 290,000 Texans either signed up or were drafted during the war. Many were from right here on the South Plains. I’ve had the honor of interviewing 40 Korean War Era veterans over the last several years. Here are a few of their experiences during this time period of the war:

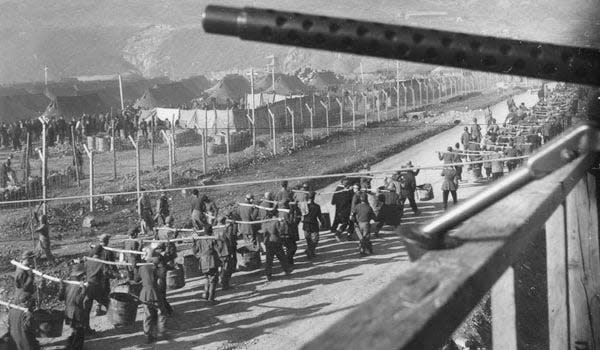

Former Lubbock resident Sgt. 1st Class Cleveland “Buzz” McMillan arrived in Korea with the Army’s 38th Regiment, 2nd Infantry in October 1951. Initially, he carried a BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) on patrols, but due to a shortage of cooks, he would soon “be serving 120 to 130 men three meals a day.” As Buzz noted, “It wasn’t an easy task with the incoming and outgoing artillery shells. Our 1st Sergeant was killed by a shell fragment.” Even the seemingly safe task of feeding the troops was often under extreme duress. Later on, his unit was transferred to a prisoner of war camp at Koje-do, an island off the southern coast of Korea. The camp would become the largest POW camp allowed under the Geneva Convention rules housing up to 170,000 prisoners. Buzz “remained at the camp for three to four months and sent back to the frontlines.” He left Korea in August 1952.

Pfc. James Cathey from Quitaque recalled, “I was assigned as a sniper. My first rifle was a Springfield M1903 bolt action with a Weaver scope. My rifle was destroyed by during combat, and I was assigned a BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle). I became proficient enough to hit my target at 750 yards.” Pfc. Cathey had many close calls during Korea and was wound twice by mortar shrapnel and awarded two Purple Hearts and a Combat Infantry Badge. Pfc. Cathey was close to the famed Pork Chop Hill. James found out later that one of the squad leaders on that hill was a Sgt. Blocker.

Sgt. Blocker was from a little town just 46 miles south of Lubbock called O’Donnell. Dan Blocker weighed in at 14 pounds at birth and was always a “big boy”. In Korea, Blocker and his unit, the 179th Regiment, 45th Infantry were in heavy fighting for 209 days. In the summer of 1952, Blocker was wounded in action coming to rescue some fellow soldiers. He was awarded a Purple Heart and other medals for his actions. Years later Dan Blocker would star as Hoss Cartwright on the popular TV western, Bonanza.

Former Lubbock resident Sgt. Bill Bridge said, “We attacked Triangle Hill (Operation Showdown) on Oct. 14, 1952. Out of 140 men that went up that hill only 14 of us made it to the top. I had six hand grenades and threw them in three bunkers to stop the Chinese from firing down on us. That’s when I was hit. Blood was gushing from my leg, so I applied a tourniquet with my belt.” Sgt. Bridge was awarded the Bronze Star, Purple heart and Combat Infantry Badge for his service.

In late December 1951, the Eight Army’s commander, Lt. General Walton Walker died in a traffic accident north of Seoul and was replaced by Lt. General Matthew Ridgway. The major battles during 1951 were, the Third and Fourth Battles of Seoul, the Battle of Imjin, Kapyong, Bloody Ridge, The Punchbowl and the Battle of Heartbreak Ridge. In 1952, major battles included the Battle of Old Baldy, White Horse and Triangle Hill. Armistice talks would continue while thousands on both sides would perish.

Next week: The fighting continues, the armistice and the aftermath.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Remembering Korea: West Texans made an impact as the war ramped up