Remembering a major leaguer's last bombing run

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It strikes me, as Memorial Day approaches, that one of the great casualties of war is promise.

I look at someone like Elmer Gedeon, proud alumnus of the University of Michigan, and I wonder what heights he might have reached had he decided to stay on the ground one afternoon in April 1944. Or maybe, in flying and dying, he came as close as he ever could to immortality.

He comes to mind most years around this time, and the years he doesn't, I feel almost guilty afterward for not marking what he did and what he gave. He was a Wolverine, a pilot, a casualty, and in the end, an unfortunate curiosity — one of only two major league baseball players killed in World War II.

More: In death, science fiction maven Alan Clive takes trip of a lifetime

More: Examining the case for a ban on body armor after mass shooting in Buffalo

Some 298,000 Americans died in service from 1941-45. We don't know, and wouldn't think to ask, how many were barbers or plumbers or insurance agents.

Ballplayers are easier to quantify, and in Gedeon’s era, the game was truly the national pastime. So we know that Harry O'Neill, who had caught one inning in one game for the Philadelphia Athletics, was shot by a sniper on Iwo Jima on March 6, 1945.

And, we know that Gedeon had already been recognized as a hero before he went overseas. “I had my accident,” he’d said jauntily then. “It’s going to be good flying from now on.”

Superstars who survived

Some ballplayers spent the war in far cushier roles than his, as P.E. instructors or stars on teams that played against other military bases. Baseball was considered good for morale — and losing a superstar in combat could only be bad for it.

Joe DiMaggio, embarrassed by his breezy Army life in Hawaii, eventually asked for a combat deployment but was refused.

Ted Williams, however, who would be recalled and fly 39 missions during the Korean War, was awaiting assignment as a replacement pilot when the Japanese surrendered. The Tigers' Hank Greenberg spent 47 months in uniform, the most of any player, and finished his tenure scouting bombing targets in the China/India/Burma theater.

Gedeon, a much lesser baseball light, was drafted along with thousands of others to no acclaim.

He trained, he deployed, he fought. High above St. Pol, France, he became an unfortunate footnote in history.

A standout in three sports

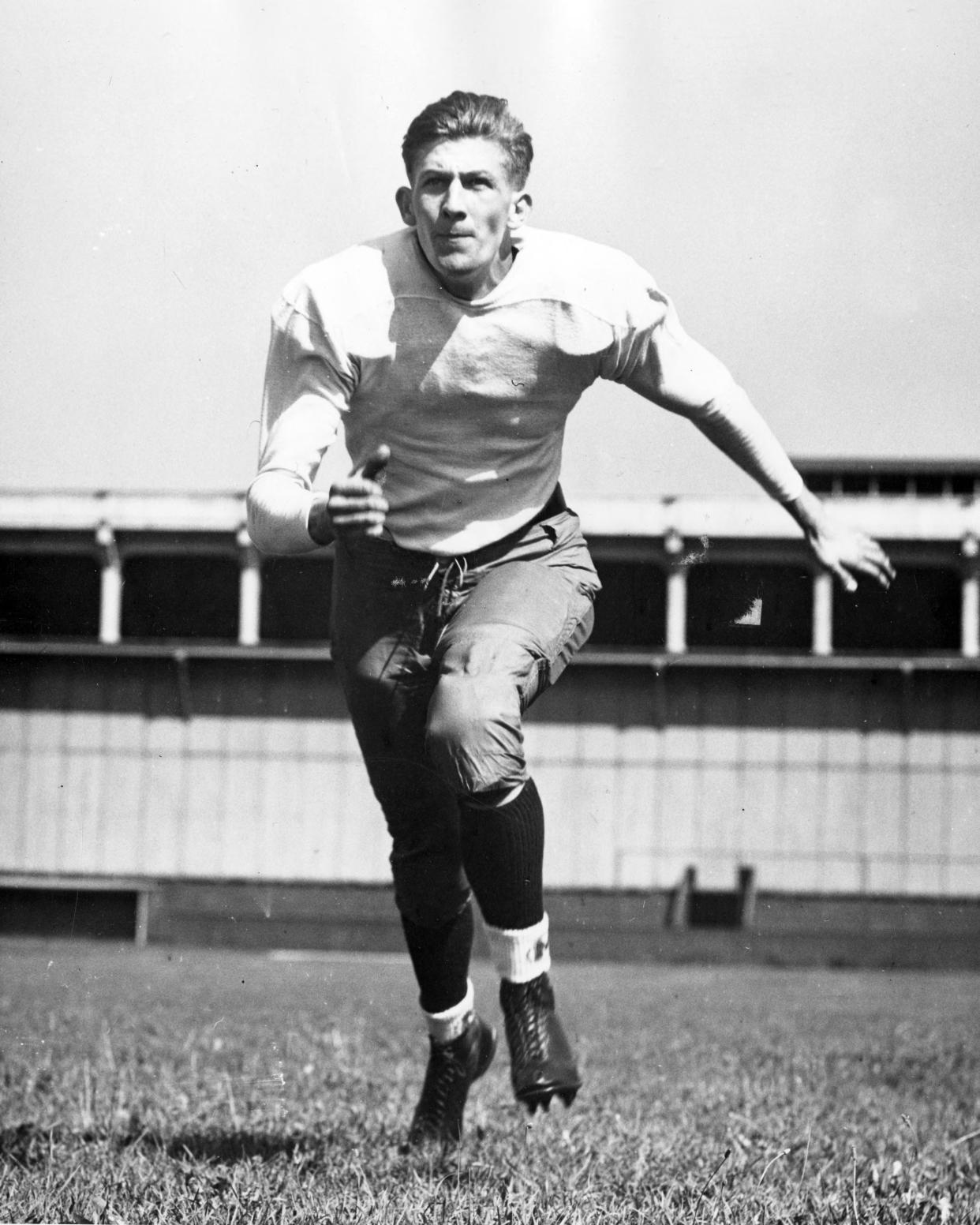

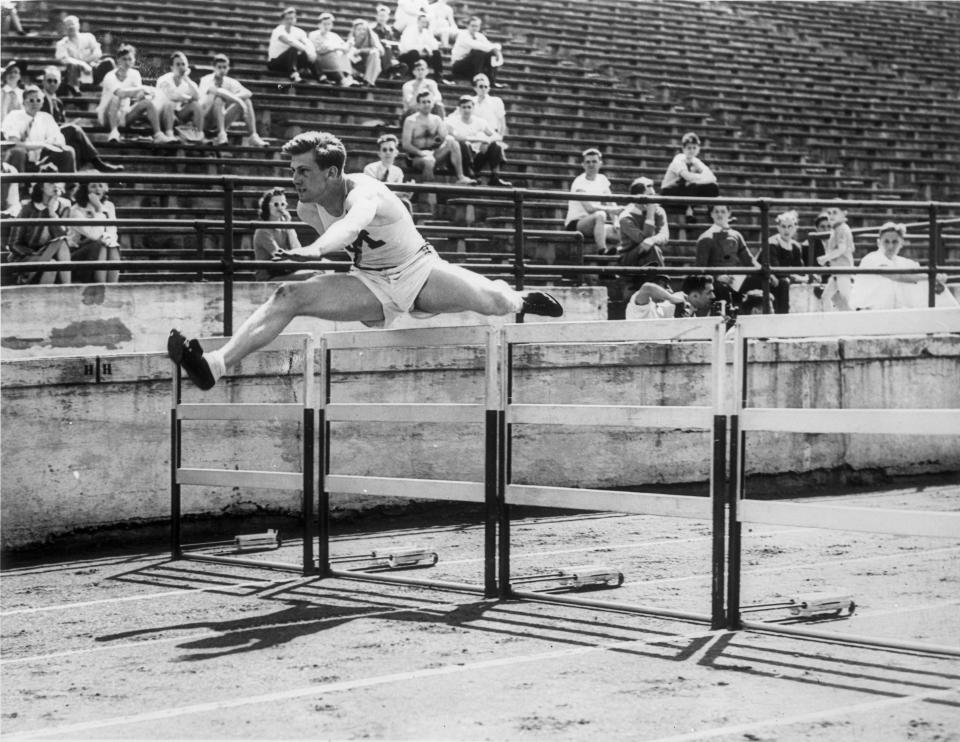

Gedeon was born in Cleveland in 1917. He was unusually tall for his era at 6-foot-4, and unusually fast: In 1935, the year the Tigers won their first World Series, he ran the 120-yard high hurdles in a state-record 15 seconds.

He was already bold. He and his cousin, Bob Gedeon, liked to ice skate at a park in their hometown. One day Bob plunged through the surface, he told an interviewer decades later, and found himself submerged "up to my neck. Elmer slid across the ice on his belly and pulled me out."

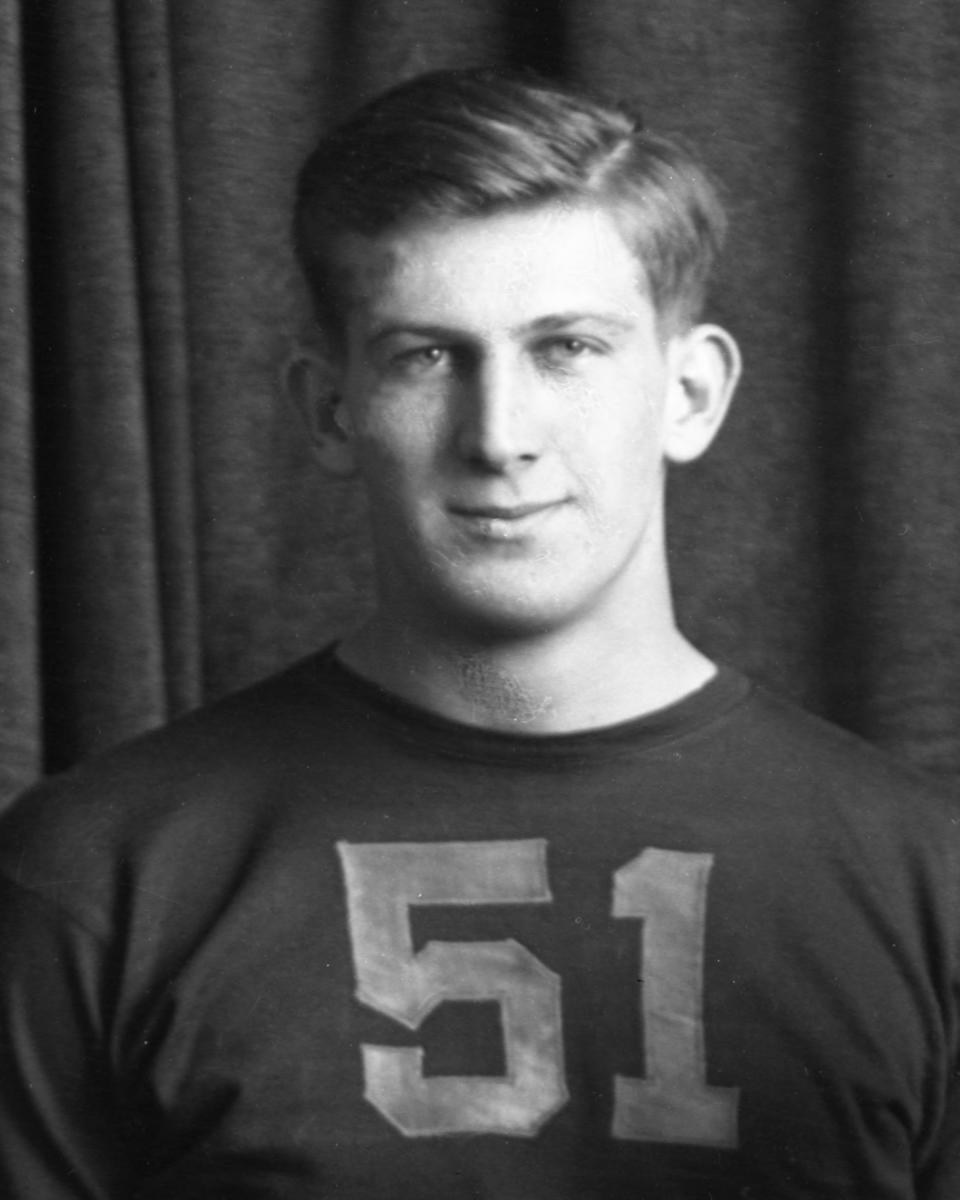

Elmer went on to Michigan, where he played end on the football team when that meant both offense and defense. On the baseball team, he played first base, though the Washington Senators would later watch him run and decide to reposition him in center field. On fraternity row, he was president of Phi Gamma Delta.

Though he resisted track and field, he finally came out for the team as a junior and started setting records. He would run hurdles in the morning, change from shorts to knickers, and spend his afternoon on the diamond.

In 2005, I found one of Gedeon's former football captains in Jackson. "A very fine guy," Fred Janke said. "A perfect guy. Everybody liked him."

Janke, 88, was by then a Navy veteran, a retired president of Hancock Industries and a former mayor of Jackson. He played guard and tackle alongside Gedeon on the line in 1938, Fritz Crisler's first year as coach and the first season of the winged helmet, even if it was leather.

"A rather serious kid. He could kick quite well," recalled Janke, who died at 91 in 2009. "They used to pull him back in serious situations and let him punt the ball, because he could punt it a mile."

Gedeon's favorite sport was baseball, and he signed with the Senators even though it meant passing up a likely spot in the 1940 Olympics in Finland — which wound up canceled anyway.

He made his major league debut on Sept. 18, 1939, as a late inning replacement against the Tigers. The next day he collected three singles against the Cleveland Indians.

Those wound up his only hits in 15 at-bats, giving him a .200 average across five games. The next year, he played in the minors. The same was likely in store for at least the start of 1941, but Uncle Sam needed him more than the Senators did.

Ballpark to bomb squadron

Gedeon was initially assigned to the cavalry, even though "the only horse I ever saw in my life was the one the milkman used."

He'd been transferred to the Army Air Corps and was serving as the navigator in August 1942 when his B-25 bomber clipped pine trees at the end of a runway in Raleigh, North Carolina. He crawled from the wreckage as it caught fire in a swamp, then realized one crewman was still aboard.

Ignoring three broken ribs, Gedeon went back inside and dragged Cpl. John Rarrat to safety. Rarrat died shortly after, because not everything is a fairy tale. Gedeon spent 12 weeks laying facedown in a hospital, recovering from burns severe enough to need skin grafts.

Twenty months later, on April 20, 1944, five days after he turned 27, he was serving as operations officer for the 586th Bomb Squadron at a base near Chelmsford, England. Though not a regular pilot, he took command of a B-26B bomber on a mission to wipe out a V-1 missile launch site in Bois d'Esquerdes, France.

The only survivor to parachute from Capt. Gedeon's plane said anti-aircraft fire hit just beneath the cockpit. Gedeon slumped over the controls as the plane spiraled into the ground.

He was buried in St. Pol. Later, his remains were relocated to Arlington National Cemetery.

His tombstone provides the basics: name, state, rank, squadron, war, dates of birth and death.

But he was also a Michigan Wolverine, a Washington Senator and a medal winner who wormed into a burning wreck to save somebody. He had a sense of humor. He had a future, whether that meant a ballfield or a boardroom.

He was real. I make it a point to remember that, at least once a year.

Neal Rubin is one of three sons of a B-17 radio operator and waist gunner who made it home. His columns appear on Thursdays and Sundays. Reach him at NARubin@freepress.com, or follow him on Twitter at @nealrubin_fp.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Remembering Elmer Gedeon, one of two major leaguers killed in WWII