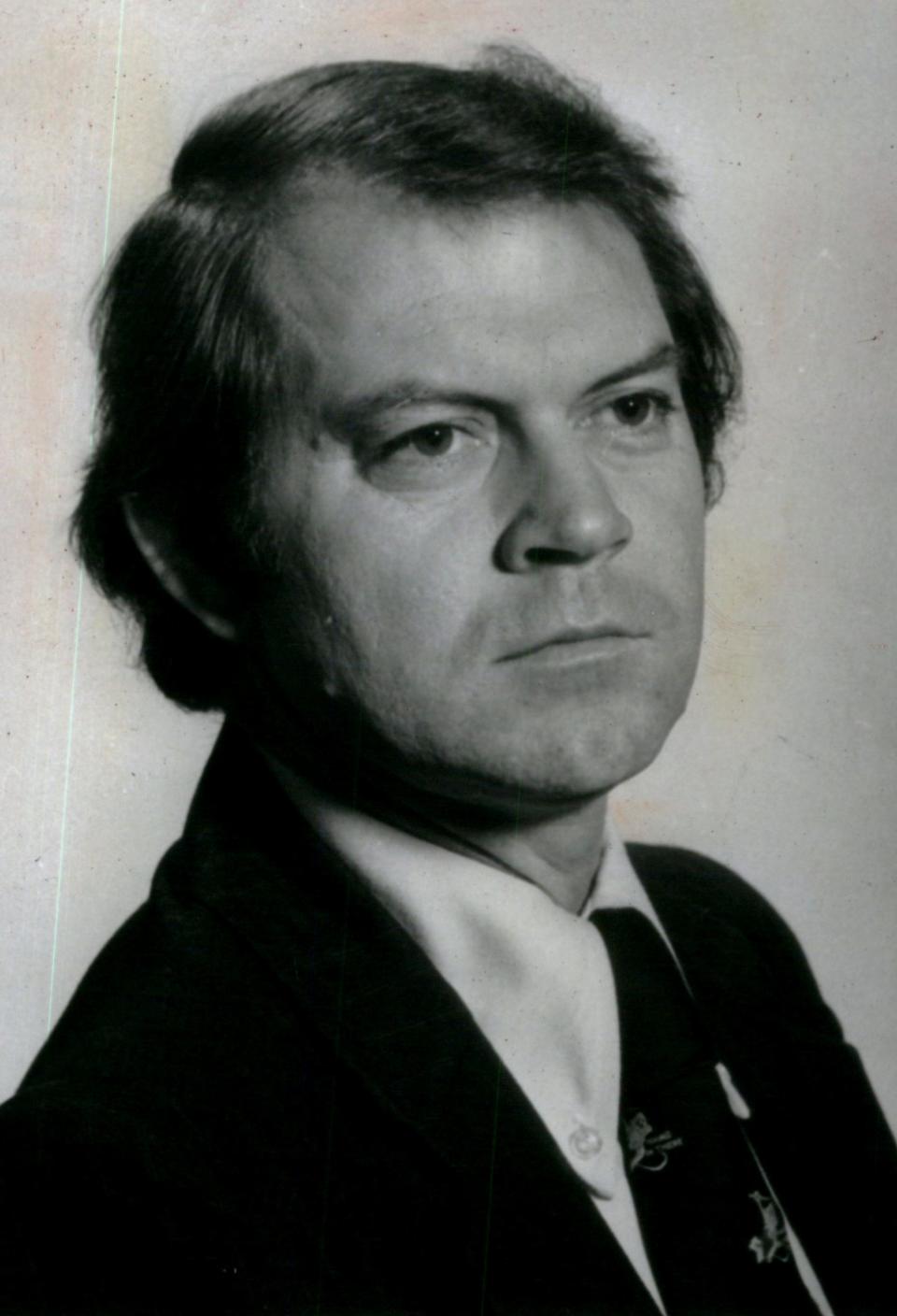

Remer Tyson, longtime Free Press correspondent covering politics and Africa, dies at 89

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Remer Tyson, the Free Press political writer who covered a half-dozen presidential races for the newspaper and later chronicled the rise of Nelson Mandela in South Africa, died Dec. 27.

He was 89, and lived in Harare, Zimbabwe, said his daughter, Beth Tyson. His wife, Virginia Knight Tyson, attributed the death to heart complications.

Born in 1934, Remer Tyson grew up in the pre-television rural Georgia. “That background had a lot to do with his extraordinary storytelling abilities,” recalled Lou Heldman, a former Free Press reporter who later became publisher of the Wichita Eagle. “I asked him once: ‘How did you become such a great storyteller?’ He told me people would gather on front porches and exchange tales when he was a kid. It was what you would do for entertainment.”

After attending the University of Georgia and working at the Columbus, Georgia, newspaper, Tyson joined The Atlanta Constitution, where he became its political editor. With the South in turmoil during the Civil Rights era, the newspaper was noted for its anti-segregationist stance, making it one of the most controversial outlets in the South. Its publisher, Ralph McGill — whom Tyson admired — won a Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing in 1959 for an essay he wrote in 20 minutes after the bombing of an Atlanta synagogue, the latest in violence in the South. “It is an old, old story. It is one repeated over and over again in history. When the wolves of hate are loosed on one people, then no one is safe.” That kind of writing became Tyson’s model for fearless journalism.

After McGill died in 1969, Tyson was persuaded to come north by James K. Batten, according to Tyson's wife. Batten joined the Free Press as an assistant city editor in 1970, and later became chairman of Knight-Ridder, Inc., the paper’s parent corporation.

Tyson’s reporting made him one of the most influential political reporters of the era. The newspaper’s coverage of presidential, U.S. Senate, gubernatorial and city of Detroit mayoral races during the next several decades bore Tyson’s stamp.

“Remer was an institution in Michigan politics back in the 1970s,” recalled former Gov. James Blanchard. “He seemed to know everything about everyone. Other journalists trusted him to know what was really going on.”

Tyson often worked closely with fellow Free Press reporter Billy Bowles, also a native of Georgia. “The two of them were like brothers,” recalled Scott Bowles, the senior Bowles’ son. “They shared Southern roots.”

“The three words, ‘Bowles and Tyson,’ became a shorthand reference to some of the best political reporting in Michigan in the 1970s,” said Bill Mitchell, another former Free Press reporter. “It was a far more bipartisan time, and Democratic as well as Republican politicians answered their phones with a mix of respect and trepidation when either of them called,”

Mitchell recalled discussions among members of the Republican National Committee about where to hold the 1980 Republican convention. “The RNC barred reporters from the D.C. hotel ballroom where they were convening but they didn't say anything about listening through the walls. We used the old trick of holding a glass to an ear and leaning against the wall to discover that Detroit was their pick.”

The Free Press newsroom was filled with reporters in their 20s. Tyson became their mentor, in addition to becoming a colorful newsroom character. He was famous for the bottle of Jack Daniel’s he stowed in his desk for use on election nights.

Said former Free Press reporter Kirk Cheyfitz, who was 29 when he covered the 1976 U.S. Senate race between Donald Riegle and Marvin Esch; “He saw reporting as an important responsibility. He felt that facts, alone, didn’t tell the entire story. You had to make judgments, but judgments based on facts. I learned so much from Remer.”

In what may have been the capstone of his political writing career, Tyson and Bowles drove around the South for three summers in a dilapidated tan and white Volkswagen bus as they wrote “They Love a Man In the Country.” Published in 1989, it was a series of rollicking vignettes of old-style Southern politicians, including the late George Wallace — who had a sometimes-contentious relationship with Tyson. Upset at Tyson’s negative account of Wallace’s flagging presidential campaign, Wallace once got off a plane, took a look at Tyson, and said: “It ain’t crumblin’, Remus.”

“Their feeling was that this world was disappearing, and would vanish altogether when these people died,” said Scott Bowles, about the book. “And, man, they worked hard on that. They just disappeared in a room, my dad at the typewriter, Remer looking over his shoulders. We didn’t see them for weeks.”

When Knight-Ridder Inc. opened bureaus around the globe, Knight-Ridder assigned Tyson to a post in Zimbabwe, where he covered sub-Sahara Africa. It gave him a front-row seat to the death of apartheid, the rise of Nelson Mandela and the genocide in Rwanda.

Asked to describe his life after retirement in 1997, he told Harvard’s Nieman Fellowship publication: “We have 2 acres inside the city that haven't been designated a farm and therefore cannot be confiscated — yet. For our use, we grow small-scale crops of corn, potatoes, tomatoes, onions, artichokes, and herbs. Our specialty is sweet basil for making pesto. Not many people in Zimbabwe know what pesto is and fewer eat it. I supply those who do. We also grow bananas, mangoes, paw paws, and avocados."

Besides his wife, Tyson is survived by a daughter, Tera Elizabeth Tyson; a sister, Kay Tyson Hart (Ray); grandchildren; great-grandchildren; several nieces, and nephews.

A memorial service will be held at Bethlehem Primitive Baptist Church in Statesboro, Georgia, with details to be announced.

Tim Kiska, a former Free Press reporter, is a communication professor at the University of Michigan—Dearborn. He can be reached at tkiska@umich.edu

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Remer Tyson, longtime Free Press correspondent, dies at 89