Remodeled downtown park to tell the story of Wichita sit-in, which sparked a movement

For three weeks in the summer of 1958, young protesters sat defiantly at the lunch counter of Wichita’s Dockum Drug Store, waiting to be served.

“As far as we were concerned, it was the right thing to do,” said Galyn Vesey, now 85. “All we wanted was to purchase food and drink just like anybody else.”

Wichita’s NAACP Youth Council staged the first successful student-led sit-in of the civil rights movement, leading the drug store chain to desegregate all of its Kansas lunch counters 19 months before the better known Woolworth’s sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Now, the city has committed $1 million to remodel a downtown park to tell that story and highlight more of Wichita’s Black history.

Finlay Ross Park, the half-acre of land just east of Century II on Douglas, will be the new home for the 20-foot-long bronze sculpture by Georgia Gerber that pays homage to the desegregated lunch counter. It was removed from Chester I. Lewis Reflection Square Park last September.

Wichita City Council member Brandon Johnson said the Kansas African American Museum will collaborate with the NAACP to tell the story of the Dockum sit-in at the new park.

“Much like the Chester Lewis park, you’ll have a bunch of art but also historical facts and hopefully some digital pieces as well,” Johnson said.

That could include QR codes that can be scanned to view interviews with sit-in participants, he said.

Lewis, the youth council’s adult adviser and a lawyer on the legal team that successfully argued Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, stood by the high school and college students as they planned and staged the peaceful protest. The national NAACP was unwilling to sanction the sit-in for fear that it could incite violence.

“He told us — parents wouldn’t tell us that — but if you get thrown in jail, I’ll get you out,” Vesey said of Lewis. “And that was all we needed to hear.”

The sit-in sculpture was removed from the Lewis pocket park in preparation for that park’s own redesign, which Johnson said aims to give a more holistic look at Lewis’ legacy. Plans for the updated space include a concrete rendering of Wichita’s “redline” map, which shows the pattern of segregation in the city caused by overtly racist housing policies.

Johnson said he expects the city to issue a request for proposal to redesign Finlay Ross Park by January. He said there’s currently no timeline for the remodel project, which he expects to cost more than the $1 million approved by the council in the August budget.

“That architect or design team would be able to tell us what that final cost would be,” Johnson said. “Minus the design fees, the rest of the city dollars will probably go towards that amount, and the NAACP will be tasked with leading a fundraising effort for the rest of it.”

Local NAACP President Larry Burks confirmed the branch’s commitment to raising funds for the project.

“Citizens should support this effort and recognize the impact this continues to make on all of us,” Burks said in an email. “It will definitely bring long overdue recognition to the accomplishments of the African-American community here and we will need the entire city to support and visit this site once completed. We need all to take pride in the history of this moment because it is our collective history.”

Finlay Ross Park, named after a former mayor of Wichita who served at the turn of the 20th century, will be renamed during the remodel process, a city spokesperson confirmed.

‘It’s still necessary’

Johnson said he’s excited to create a space for people to “see the beauty of art but also learn the depth of history.”

He said many people haven’t even heard of the Dockum sit-in, which was emulated in a wave of peaceful protests at lunch counters across the south that in turn inspired wade-ins at white-only swimming pools and pray-ins at white-only churches.

“It’s not talked about in schools. I don’t think it’s in any of the textbooks,” Johnson said. “It’s something that many of the participants of the Dockum sit-in are just so humble about. They never really talked about it until probably the last eight to 10 years.

“Now, we see the power of what happened and how it was duplicated around the country.”

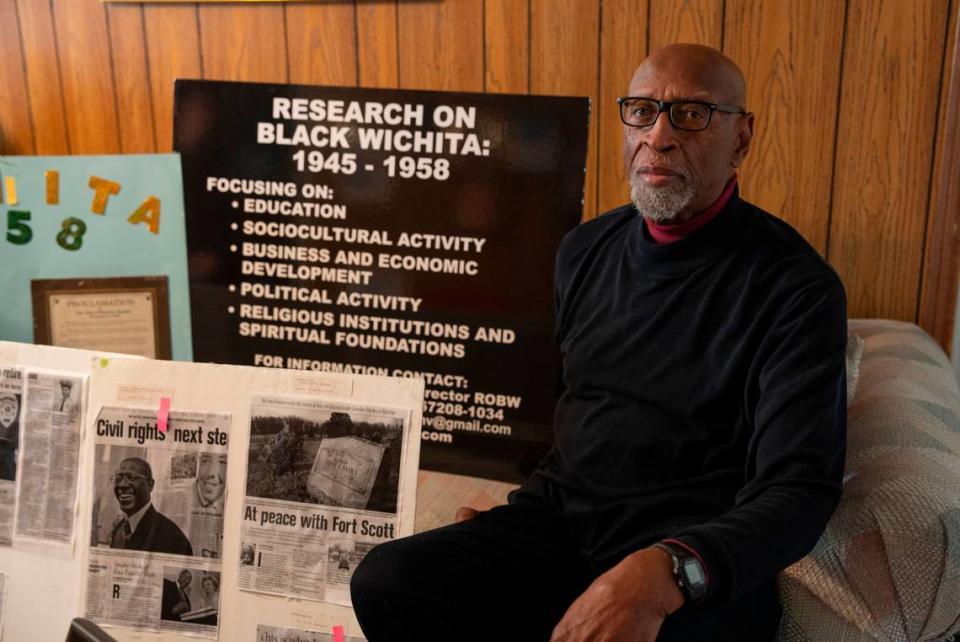

Vesey, a retired professor and project director of Research on Black Wichita: 1945 – 1958, said he supports the collaborative effort to bring more visibility to the pivotal moment in civil rights history.

“It’s still necessary,” Vesey said.

“We take one step forward, another half step, and then we take one step backwards.”

At the time of the sit-in, racial segregation was technically illegal in Kansas under an 1874 civil rights statute. That didn’t stop local businesses from engaging in discriminatory practices against people of color.

“So-called minorities in general, you knew where you belonged. You just did,” Vesey said. “And if you didn’t, you found out.”

Dockum’s lunch counter was reserved for white patrons only, as were many such eateries in the U.S. in 1958. Black patrons could order take-out or stand.

“There was a place in some of the stores where we could stand and eat it, but we couldn’t sit down,” Vesey said.

“My mom was good enough to go to Eastborough to take care of white children and cook meals for white families, but when she came back to town . . . she’d ride the bus back downtown and while waiting for the bus that would carry her close to home, she might want to go inside to Dockum’s or McLellan’s or Woolworth’s — one of them — and get a Coke or something,” Vesey said. “A human experience that was perfectly understandable, one would think. But no, that was out of the question.”

In the summer of 1958, Vesey’s parents didn’t know he was participating in the sit-in. He told them he was playing basketball at the YMCA, worrying that his father could lose his job if his boss found out about the 20-year-old “raising hell” at Dockum.

Unlike some of the subsequent demonstrations in the south, participants of the Wichita sit-in were not violently targeted by counter-protesters. The youth council spent weeks preparing for the sit-in in the basement of St. Peter Claver Church, where they practiced keeping their emotions in check while some members role-played as confrontational white people.

The roughly 20 demonstrators who alternated shifts during three weeks of peaceful protest maintained their composure throughout. Vesey distinctly remembers the moment when Dockum management relented and agreed to serve Black patrons at the lunch counter.

“One day when we were sitting at Dockum’s, a few of us, and the management came by and told us that we could get stuff to go but we really shouldn’t be sitting there,” Vesey said. “Well, I set there a few minutes and just something inside me prompted me to get up and go talk to one of the clerks that we weren’t trying to cause trouble. We didn’t want them to lose business but we wanted to get a Coke or sit at the counter just like anybody else.

“One of the clerks said, ‘There’s nothing I can do about it,’ so she did go get the manager. Manager came, gave us the same song and dance, and out of the blue said, ‘OK, I’m losing too much money. Go ahead and serve them.’ And that blew us away.”

Lewis later spoke with the vice president of Dockum Drug Stores and confirmed that the chain would end its discriminatory serving practices toward patrons of color.

Johnson said part of the planning for the remodeled park will include meeting with surviving members of the sit-in, who are all in their 80s. Vesey said he welcomes that opportunity.

“I’m proud to call Wichita home now,” Vesey said. “There was a time I wasn’t so sure.

“We have come a long, long way as a people, one. Two, but we still have a long, long way to go.”