Remote, stealth commands tamper with temperatures in Portland area homes — all to save energy

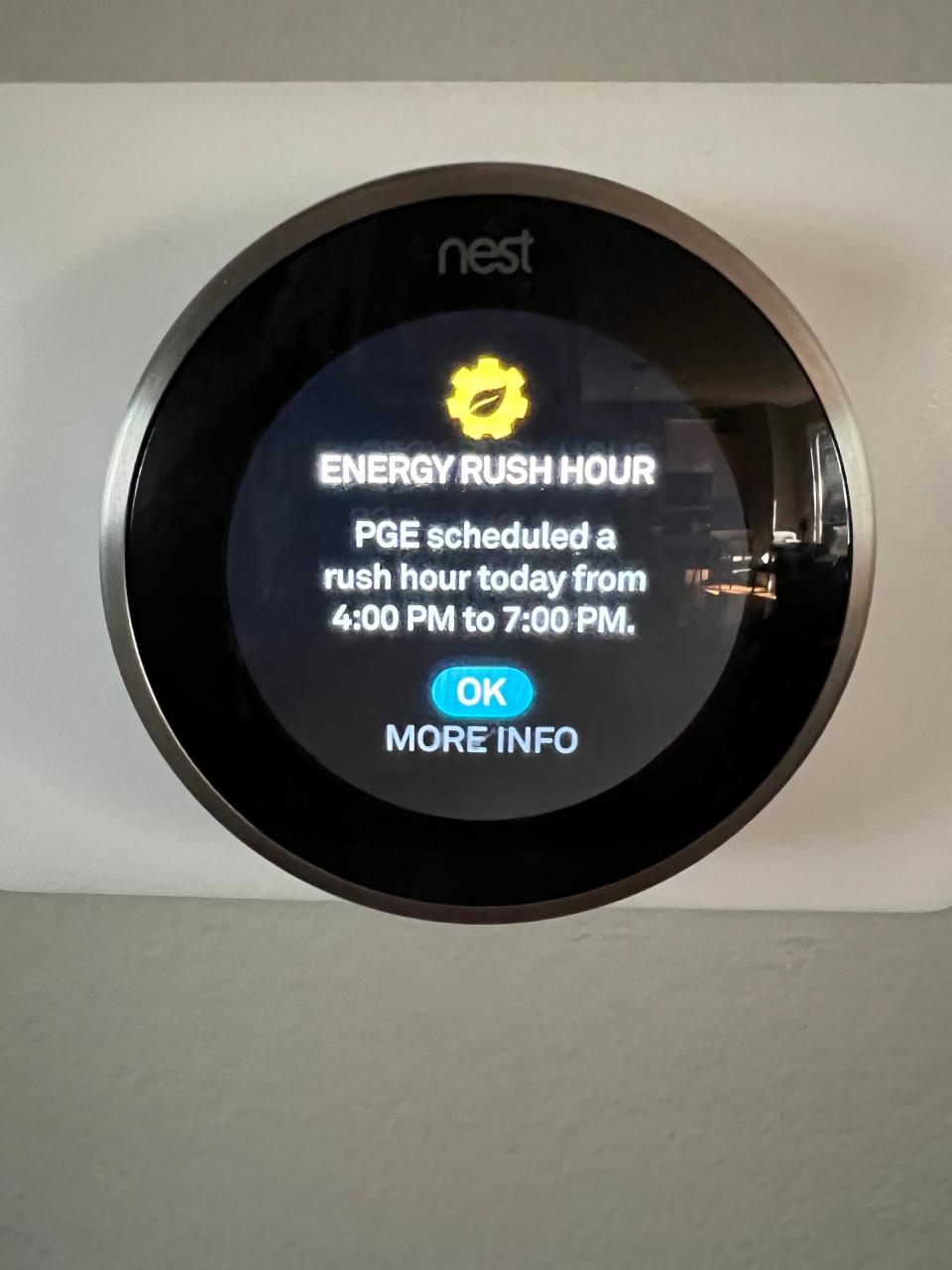

In the early hours of Wednesday, Portland General Electric's computers sent a remote, stealth command to Michael Irving's thermostat in Tigard, Oregon, telling it to turn itself down a few degrees.

Another command came at 4 p.m. – set the temperature up a few degrees.

Far from being upset at the invisible tampering with his family's air conditioning, Irving was pleased.

"It's not like the house was 100 degrees or something or we were sweltering," he said. Instead, it simply went up from their usual 75 to a little closer to 78.

Temperatures in Irving's corner of the Pacific Northwest, normally mild, hit 97 on Wednesday, with a forecast of 102 Friday and Saturday as the area endures an unusually long heat spell.

In years past, such intense demand on the electrical grid might have resulted in rolling brownouts or even blackouts. Instead, the grid is holding, in part due to a voluntary program Irving and 100,000 other PGE customers have signed up for in the past few years.

CLIMATE POINT: Subscribe to USA TODAY’s free weekly newsletter on climate change, the environment and the weather

Called voluntary energy shifting programs or demand response, customers grant their utility the right to slightly lower their energy use when power demand spikes, in return for a small credit on their bills.

"It saves me a few dollars," said Steve Koper, who signed up for the program in 2020.

The temperature difference inside his house is so minor he doesn't notice it, a minuscule shift he's happy to make.

"It's a small change that saves me a few dollars and helps the community during times like this heat wave, so it’s a win-win," he said.

PGE's energy shift encompasses several programs, said Larry Bekkedahl, the utility's senior vice president of advanced energy delivery. One raises or lowers willing customers' thermostats slightly when heat waves or cold snaps create short-term power crunches.

Another, for apartment buildings, turns off large hot water heaters from 4:00 to 7:00 pm, when power usage is highest – without leaving them in the lurch.

"There's enough residual heat that it's still hot," Bekkedahl said.

Everyone who signs up gets 24 hours' notice, via email or text, and can opt out of the program at any time.

"You're never forced against your will," Irving said. "Though if you override it more than 50% of the time, you lose out on the credit."

These programs are a little like an airline offering customers a travel voucher in return for taking a later flight, said Steven Nadel, executive director of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

In Portland, these invisible commands, sent through to customers’ smart electricity meters, allowed it to drop demand by 62 megawatts during the worst of last year’s June heat wave, avoiding rolling blackouts and possibly permanent damage to overheating equipment.

That 62 megawatts is the equivalent of energy for 25,000 homes.

“We’ve started to use the term ‘virtual power plant’ and that’s how we think about it,” Bekkedahl said. In the next three years, the utility hopes to build the program out so that it can cover over 200 megawatts of flexible energy load.

These programs have long been in place with industrial and business customers at utilities around the country. A steel plant or aluminum smelter might sign a contract saying it would voluntarily reduce production when power demand is high and electricity expensive, in return for rate reductions.

With the advent of smart meters in houses, which allow communication between the utility and a customer's home, that kind of flexibility is now a possibility for regular consumers as well.

Dozens of utilities nationally, including Baltimore General Electric, Con Edison, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric have put similar programs into use.

In some areas, the shift is done automatically through a smart thermostat or connected appliances such as water heaters. In other places, customers get texts or emails asking them to manually lower their energy use, said Xin Jin, a senior researcher at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colorado.

As heat waves become more common and more intense due to global warming, such programs help utilities cope with enormous spikes in demand without needing to build more power plants.

"Demand response is going to be critical for helping manage peak loads," Nadel said.

Utilities that make use of these programs can reduce peak electricity demands by around 10% he said. Utilities most often tweak settings on air conditioners, water heaters and pool pumps.

"In Southern California and Arizona, they're big on these for pool pumps," he said.

The energy savings for an individual house might not be that big but in Portland, where almost 1 in 10 customers now take part, it adds up.

"There's plenty of power to go around," Irving said. "It should be more of a team effort for us to figure this out."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Demand response programs let utilities remotely change temperatures