Renewing the Black-Jewish alliance — it's what Dr. King would have wanted

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

How weird, tangled, contradictory are Black-Jewish relations in 2023?

Two words. Whoopi Goldberg.

The "View" star — one of several celebrities to get into hot water for troubling remarks about Jews — was born Caryn Elaine Johnson.

The "Goldberg" was pure imagination. Cross-cultural empathy. "Claiming kin," as they used to say in England.

In her 1984 one-woman show "Whoopi Goldberg," she played a "street" character named Fontaine, who accidentally boards a plane to Amsterdam and winds up at Anne Frank's house. "I always thought when you went into hiding, it was like moving from one apartment to the other," she says.

That, too, was claiming kin.

The African American experience and the Jewish experience are both rooted in trauma. Slavery, and Holocaust. Racism, and antisemitism.

Those twin horrors have always given the two groups a special bond. But it hasn't prevented misunderstanding, mutual suspicion. Nor, in these days of rampant hate speech, localized outbreaks of ugliness.

Goldberg's comment that the Holocaust was "not about race" got her suspended from "The View" last year (she later apologized). There has been worse. Rapper Ye and basketball star Kyrie Irving made recent headlines for even more inflammatory stuff.

All this, of course, is in the context of a general rise in bigotry that is targeting both Blacks and Jews. The same white thugs who marched in Charlottesville in 2017 with Confederate flags also shouted "Jews will not replace us!"

So what now? What can we do about it today, this January — the month of Martin Luther King Jr. Day (Monday, Jan. 16), honoring the man who gave his life so that people of all races might get along? What can we do about it in 2023 — the 60th anniversary of the "I Have a Dream" speech?

"We have to try to figure out how to rekindle the relationship between the African American and the Jewish communities," said Paterson historian Jimmy Richardson.

Making a start

He's doing his part on Jan. 13.

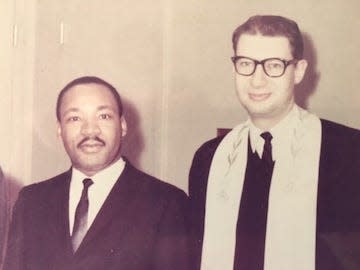

He'll be in Wayne, three days before MLK Day, delivering the annual Temple Beth Tikvah Martin Luther King lecture — established by the late Rabbi Israel Dresner, himself a monumental civil rights leader. The rabbi, who died a year ago to the day — Jan. 13, 2022 — stood by King's side, marched with him, was arrested with him.

"Dresner was a true humanitarian," Richardson said. "He not only fought for civil rights, he fought for the gay and lesbian community. He fought for the freedom of the Israeli nation. He was not just a person who did a lot of talking. He was a man of action."

It was the rabbi himself, shortly before he died, who specifically asked Richardson to deliver this year's address — an honor previously reserved for such luminaries as Andrew Young.

And Richardson is only returning a favor. A dozen years ago, Dresner spoke, by Richardson's invitation, at the landmark dedication ceremony for Paterson's Community Baptist Church of Love, one of the last places King appeared in public. That was March 27, 1968 — just a week before his assassination.

"Dresner was guest speaker," Richardson said. "From that, a wonderful relationship developed."

"All King's Men" is the theme of Richardson's Jan. 13 address, one of several events at the Reform temple on this key weekend.

A pathway in front of the building will be dedicated in the rabbi's honor, followed on Jan. 15 by the unveiling of the rabbi's headstone. And the Jan. 13 ceremonies are not limited to Beth Tikvah's congregation.

Members of the Conservative congregation Shomrei Torah of Wayne will be there as well. So will guest musician Ronald A. Foster, director of worship at Madison Avenue Christian Reformed Church of Paterson. The ceremony will be both interdenominational and interracial. And that's telling.

Shoulder to shoulder

"There was a strong alliance, during the civil rights movement, between the Black community and the Jewish community," said Rabbi Brian Beal, Dresner's latest successor.

Strong — and much noted at the time.

Not only were Jewish leaders going south to march at King's side (along with members of the white Catholic and Protestant clergy), but there were students. Most famously, there were Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, two New Yorkers who were murdered in 1964, alongside Mississippi's James Chaney, as they tried to register voters in the Deep South.

"I think more needs to be said about the alliance, because it's important for younger people to understand it," said Marilee Jackson, who, in 1980, was the first African American woman elected to the Paterson City Council.

This honeymoon period was even reflected in pop culture. In 1961, Sammy Davis Jr. converted to Judaism. In 1959, Harry Belafonte had a hit with "Hava Nagila." "Most Jews in America learned that song from me," Belafonte once said.

It all reflected a deeper kinship that goes back to the days of slavery. It's not by accident that one of the most famous spirituals was called "Go Down, Moses."

"The Jewish people have been persecuted through the generations, going back to the days of ancient Egypt," said Arthur Barchenko, a past president of Beth Tikvah. "We knew what slavery was."

For the last year, Barchenko has been meeting with a group called the Jewish/African American Alliance of Fair Lawn, an outgrowth of the Jewish Historical Society of North Jersey, and created with $2,500 in seed money from the New Jersey Council for the Humanities. The object: to renew the old ties.

"It's a group of representatives of different universities, synagogues and churches," he said. "Black and white people. We meet every two weeks. This has to be rebuilt."

Mutual aid

For more than 100 years, this bond between two of America's most abused minorities was valuable to both.

Louis Armstrong, to the end of his life, wore a Star of David around his neck. It was a tribute to the Karnofsky family — who virtually adopted him when he was a homeless 7-year-old in New Orleans. In 1909, activist Henry Moskowitz was a key founder, along with W.E.B. Du Bois and Ida B. Wells, of the NAACP.

And the aid went both ways. When Joe Louis KO'd Max Schmeling in their rematch fight on June 22, 1938, spontaneous street celebrations erupted, not just in Harlem, but in Jewish neighborhoods in the Bronx. The Brown Bomber had defeated Hitler.

In the 4th Ward of Paterson, where Jews and African Americans had been living together since the mid-19th century, relations were usually cordial, Richardson said. He has a lot of good memories of that neighborhood, where he grew up in the 1950s.

"There was a grocer at 135 Governor St., owned by Mr. Katz," he recalled. "If you didn't have the money, and you needed an extension, he would give it to you. My grandmother would send me there. She'd say, 'Junior' — she used to call me Junior — 'tell Mr. Katz to give you a dozen eggs, a box of matzos, Velveeta cheese and salami.' "

Black and Jewish kids were in and out of each other's homes. As 7-year-olds, Marilee Jackson and her friend Mildred would be taken on outings by neighbors — sometimes by family friend Mr. Herman, sometimes by his friend, Mr. Kirby. Mr. Herman was Jewish. Mr. Kirby was Black.

"They'd take us horseback riding, to the park, to the amusement park," Jackson said. "We were all neighbors. Everybody knew everybody, from Fair Street to Governor Street, and from Straight Street up to East 18th almost. That lasted for years."

Tension

So what happened to all that goodwill?

A long, complicated story. But suffice it to say that alongside the mutual respect, there was tension.

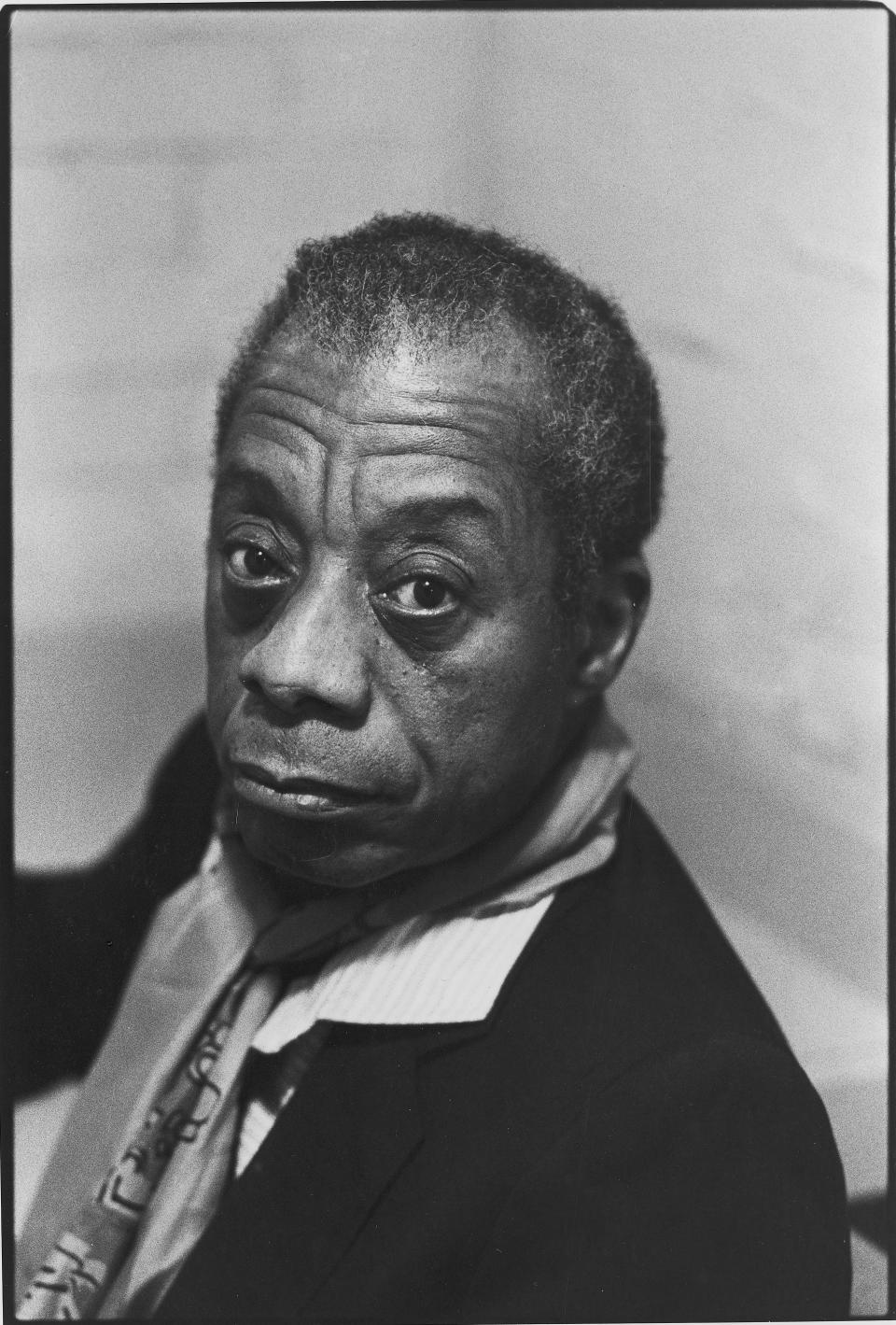

Stigmatized and excluded as they were, Jews historically had advantages that African Americans did not. That extended to the ownership of stores and tenements in Black neighborhoods. "When we were growing up in Harlem our demoralizing series of landlords were Jewish, and we hated them," wrote James Baldwin in 1967.

They were hateful — because they were bad landlords, not because they were Jewish. For some, however, that was a distinction without a difference.

"African Americans' main contact with Jews was often in the form of landlords or shop owners," wrote Judith Rosenbaum of the Jewish Women's Archive. "And some resented Jews for making a profit off their community."

And just as some African Americans resented Jews, some Jews resented African Americans for resenting them.

"I was afraid of Negroes," wrote Norman Podhoretz, who grew up in Brooklyn in the 1930s and described it — more honestly than some — in a 1963 essay in "Commentary," the Jewish conservative magazine.

Add to this, in the 1960s, the international situation: a militant Zionist feeling taking hold in some Jewish circles, and a pro-Muslim feeling gaining ground in parts of the Black Power movement. The question of who was the oppressed, and who was the oppressor, in the Middle East was divisive. It still is.

"That's a very, very complicated issue," Richardson said.

Most crucially, at the end of the day, Jews were — by America's reckoning — white. They could flee to suburbs, in the 1950s and '60s. Places where Black folks, for the most part, were not welcome.

"Most Black folks who lived in the 4th Ward were there historically forever," Jackson said. "Jewish people, and I guess Italian people, they all moved out to suburbia."

When Jewish families left places like Paterson's 4th Ward, they left them bereft. Not just of stores and jobs, but also of moderating voices. Who, living there now, could counter the antisemitic rhetoric of leaders like Elijah Muhammad and Louis Farrakhan (both of whom came to the area in the 1960s)? "You had various African American groups all vying for everybody's attention," Richardson said.

That's a lot to overcome.

But overcoming is what the civil rights movement was all about. And for all the hard feelings, Beal, the Wayne rabbi, believes that the relationship between the two groups may not be as broken as it sometimes seems.

And in any case, don't we owe it to the Rev. Martin Luther King and Rabbi Israel Dresner to try?

"I don't think it's so much frayed as it's drifted," Beal said. "I think the two communities focused on their own and other issues. And I think with the rise again in recent years of white nationalism and white supremacism, we see the needs of the Jewish community and the African American community overlap."

Extremism is a looming threat. Most of us can see that. But those who have race riots and pogroms in their background can feel it — in their bones. They need to be allies in the fight ahead, Beal said.

"We need to know each other," he said. "Take care of each other, defend each other."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Black-Jewish alliance: What happened to it?