A renowned forensic artist hopes her drawing identifies a skull found at the Alamo in 1979

SAN ANTONIO — During her four decades as forensic artist for the Houston Police Department and other law enforcement organizations, Lois Gibson has helped detectives solve more than 1,200 violent crimes and lock up some 750 of the nation's most vicious killers on the run.

Now retired, Gibson is using her talents and skills in hopes that she might help solve a mystery that is 187 years and six months old.

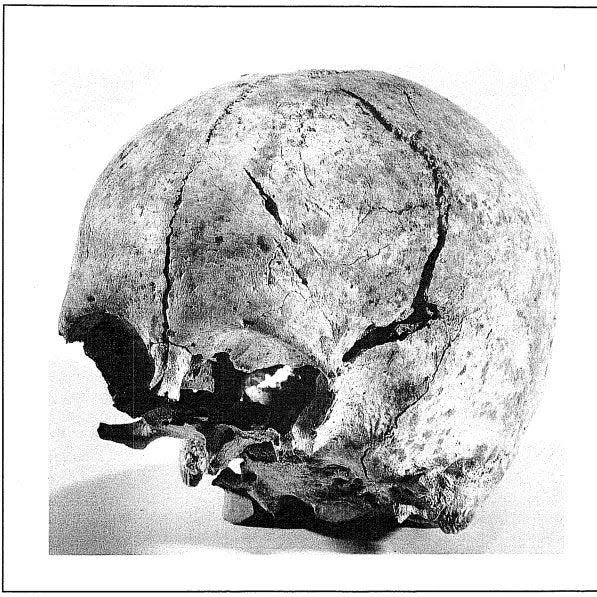

Working with Lee Spencer White, founder of the Alamo Defenders Descendants Association, Gibson has been given permission to examine the partial skull unearthed in 1979 on the grounds of Texas' most iconic battlefield and held in safekeeping by the Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio. And from that skull, she hopes a picture of the person it is from will emerge.

The skull, which was found without a lower jaw or teeth, had likely belonged a young man ranging from late teens to about 23 years old. In contains a gash from a sharp and heavy-blade, and perhaps a gunshot wound. Using features such as the shape and depth of the where the eyes and nose had been and the contours of the forehead and cranium, Gibson was able to produce a sketch after one day examining the skull from all angles.

"I may fail," Gibson said of the effort to positively identify the skull as being from one the near 200 defenders who died at the Alamo on March 6, 1836. "But I at least I got a chance to try and scratch an itch, because for years I've heard (about the skull) and I thought, 'is somebody re-creating the face on that person?'

"So I was thrilled when Lee called me."

White, a direct descendant of Alamo defender Gordon C. Jennings, has spent years trying to learn the identity of various bones found over the years on the Alamo grounds. The most recent finds, three sets of remains — one interred in a wooden coffin — were discovered in 2019 as part of the still-ongoing restoration project at the mission that sits in the heart of downtown San Antonio. White is pushing for DNA testing that might prove the bones were that of defenders.

Reaching out to Gibson to put a face on the skeleton was an easy decision, White said. Gibson was the first sketch artist contacted by television's "America's Most Wanted" and occupies a place in the "Guinness Book of World's Records" as the artist who has helped solved more crimes than anyone in her field.

"I felt you are the best person for this," White told Gibson during a joint interview with the USA TODAY Network in a hotel lobby on San Antonio's north side.

What we know about the skull found at the Alamo

in March 1979, archaeologists James Ivey and Anne Fox were hired to perform "archaeological investigations" inside the Alamo's north courtyard, according to their report available online through the Center for Regional Heritage Research at Stephen F. Austin University.

During excavation work, the skull was found in a filled-in defensive trench near what is now Houston Street north of the mission that is most associated with the Alamo complex. Ivey and Fox wrote that the skull "may have belonged to someone who died immediately after being slashed several times by a heavy-bladed weapon."

Because many young men were at the Alamo from the beginning of the siege that began Feb. 23, 1836, and ended with the climactic battle on March 6, and because many of them died violently, all signs suggested the skull was likely from one of the defenders, Ivey and Fox wrote.

More: Remains found at Alamo likely were those of a defender, descendants group founder says

"As far as we can tell, the skull is that of a participant in the Battle of the Alamo," they said in their report.

According to a 2019 report by the San Antonio Express-News, the skull was the subject of a tug-of-war involving the Texas Historical Commission, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, the Roman Catholic Church and the Inter-Tribal Council of American Indians. The Historical Commission and the Daughters wanted the skull kept in safe storage. The church and the tribal council wanted it reburied in a religious ceremony.

It was finally placed in the custody of UT-San Antonio's Center for Archaeological Research, where it presently remains.

Who is forensic artist Lois Gibson?

In 1972, Gibson survived an attack by a serial rapist and murder, and that experience offered her a chilling and real-life example of how forensic art can solve crimes. She earned her fine arts degree from University of Texas at Austin and spent the early part of her career drawing sketches of tourists along San Antonio's Riverwalk and selling the art to her subjects. That's where her connection to the Alamo was cemented, she said.

"I did (pictures of) about 3,000 people sitting there and I would visit the Alamo and I fell in love," Gibson said. "I've been there; that's my place. I feel like it's my place."

But working with crime victims and survivors became her calling. She developed the ability to coax people, some as young as 4 or 5 years old, to remember the details and features of the faces of killers and other violent offenders. She recalled helping police in Kansas solve a 2008 murder that remains seared in her memory.

"Marcos Lomas killed two parents in front of their 4-year-old son," she said. "The four-year-old son gave me (a description leading to) a sketch. We caught him. That was the first time I did a sketch from a 4-year-old. I'd done many from 5-year-olds, and I didn't know if I could pull it off."

More: Texas Historical Commission rejects plan to move Alamo monument

Lomas pleaded guilty to stabbing the couple to death and was sentenced to life in prison.

Gibson also used skeletal remains to sketch the face of a 2-year-old girl whose body was washed ashore on Galveston Island in October 2007. Three days after the sketch was released, a woman recognized the face as that of her granddaughter. The girl's parents were arrested in her death.

Three years later, Gibson used a partial skull discovered in Richmond, Texas, near Houston that was in a condition similar to that of the one found at the Alamo to sketch the face of the woman it might have been from. When the person's ID was later discovered through DNA, a photo of the woman closely matched Gibson's drawing.

Not all of Gibson's sketches are the result of crime and violence.

Seven years before his death in 2007, Glenn McDuffie of Houston claimed that he was the sailor captured in a Life Magazine photo kissing a woman in New York's Times Square after hearing that Japan had surrendered in August 1945 and that World War II was over. He just needed help proving it.

Gibson stepped up. She examined hundreds of photos of McDuffie, including some staged to re-create the iconic pose in the Life photo, and concluded the old sailor was the sailor he claimed to be. Life Magazine has never authenticated McDuffie's assertion or Gibson's affirmation. But she said at the time that she also examined photos of others making that claim to fame and concluded without doubt McDuffie was the real deal.

Will the skull discovered at the Alamo ever be identified?

White said Gibson's sketch represents the start of the journey, not the finish line. She plans to once more pore through what's known about the Alamo battlefield, where the various defenders and organized units made their stands and to review the ages of the known dead from the Texas side.

A likely place to begin, she said, is to look at a unit known as the New Orleans Grey. It was group organized in Louisiana at the start of Texas' march toward independence whose volunteers were mostly young, and not all from New Orleans. They got their name from the gray uniforms likely supplied to them by Thomas Banks, a New Orleans businessman and supporter of Texas independence whose coffee house was used as a meeting place for the unit.

The Greys were among the few uniformed Alamo defenders, and all members who took part in the battle perished.

"I'm firm believer, after researching (the battle), you go with the logical, most obvious first," White said. "And so you would have the majority of the young men in that age group in the New Orleans Grey. So we'll look at that."

White has also started a DNA database for descendants of the Alamo defenders. She said membership in her organization is not required to offer a sample. Because the skull was likely from a young man, there might be no direct descendants, she said.

However, she added, if he had siblings or cousins, their descendants might be able to provide a matching sample. Still, White said she's not getting her hopes up just yet.

"We're not going to have a definitive person, I know," White said.

Gibson agreed, but she wouldn't let go of the possibility that her sketch might provide some strong clues.

"I knew that going in," she said, referring to the long and daunting odds she and White are facing. "What if you can narrow it down to two or three?"

John C. Moritz covers Texas government and politics for the USA Today Network in Austin. Contact him at jmoritz@gannett.com and follow him on X, formerly called Twitter, @JohnnieMo.

This article originally appeared on Corpus Christi Caller Times: An artist's sketches have solved crimes. Can they to solve an Alamo mystery