Renowned Gaspar Enríquez shows love of Chicano culture, Borderland in art, adobe

Renowned artist Gaspar Enríquez has gone from El Paso's Segundo Barrio to fame as a leading artist known for his realistic, airbrush depictions of Chicano culture.

Now, he hopes to help San Elizario, which he now calls home, attract visitors and get on the tourism map.

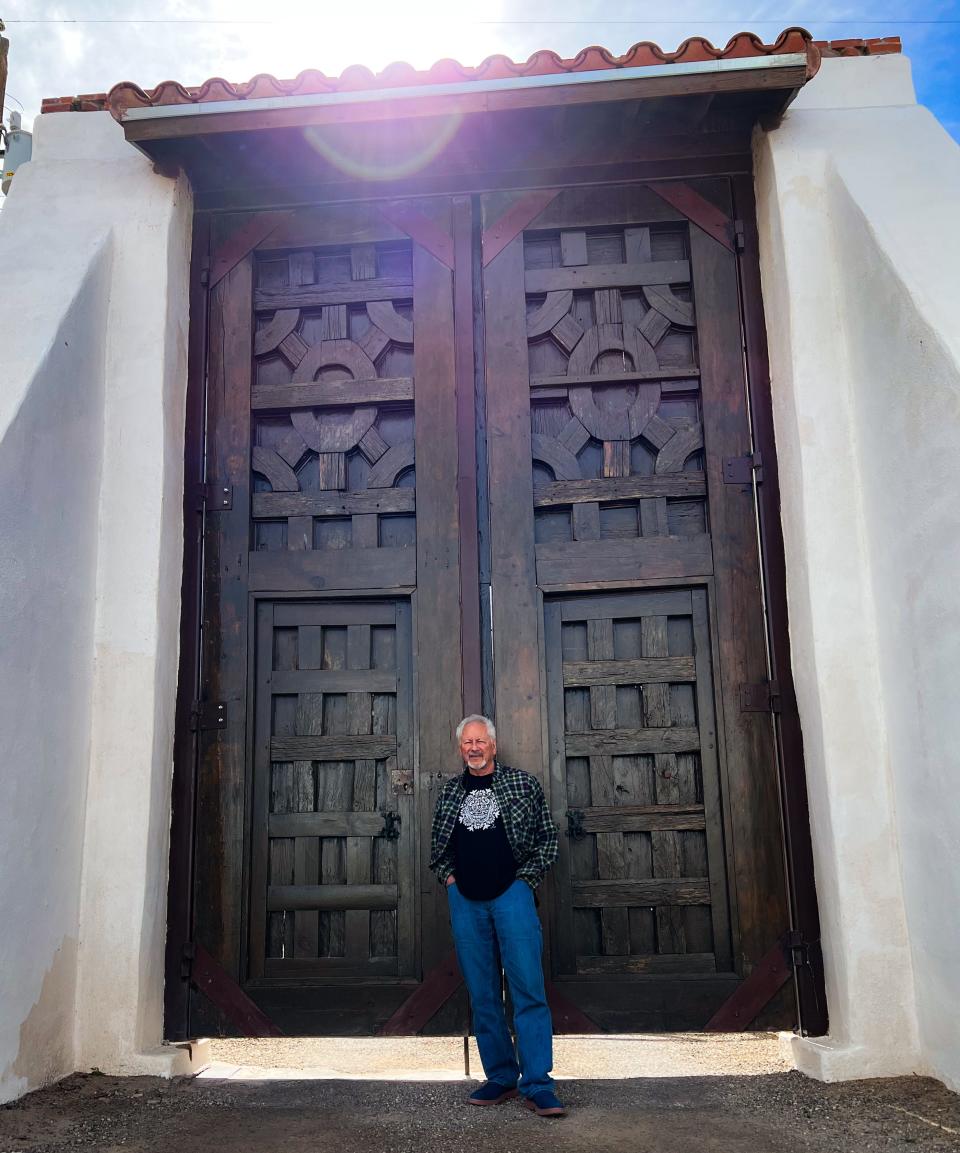

Enríquez has restored buildings in the community in El Paso County's Lower Valley into his Micasa Art Studio and Gallery. It showcases his work and that of other artists, mostly from the Borderland.

The historic adobe buildings at 1456 and 1458 Main St. in San Elizario also include a clothing store, a coffee shop, a venue available for rent and the office of a state lawmaker.

Enríquez's path to famous artist and community builder took a lot of time, turns and hard work.

“I was born in 1942 at a maternity clinic in the Segundo Barrio,” said Enríquez, who has four portraits in the collection of the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery.

“That’s where I was born, and I grew up there. My parents used to live on Park.”

He added, “I was raised there, but we actually moved a lot, and then we'd wind up back over there.”

With the eyes of the artist he always has been, Enríquez saw all aspects of life in the barrio, which perhaps colors his memories of the neighborhood.

When asked about life there, he said:

“Sometimes there wasn’t a good time. Because it was … it had a lot of problems, because as you very well know, it was the barrio, it was the ghetto. There were a lot of gangs, a lot of drugs, a lot of dysfunctional families. But because we grew up with the same type of people that we were surrounded — our neighbors and all that — we didn’t know that we were poor because everybody was poor in that area. So, as a kid, it’s a playful thing to do; it was just growing in the neighborhood.

“So, as far as growing up in the barrio, in the Segundo Barrio, the good thing about that, it was close to Downtown. You could even walk to Downtown, go to a movie or whatever. But there were some good times. There’s good people there. Good people.”

Enríquez taught art at Bowie High School for more than three decades, but as a teen went to Bowie’s rival, Jefferson.

“In the barrio that I lived in, the gangs there were rivals to the gangs in … the Bowie area, so I said if I’m gonna get beat up every day, I’d better go to Jefferson. So, I went to Jefferson until my senior year and then we moved to Ysleta. And I graduated from Ysleta.”

Although Enríquez took a circuitous route to achieving fame as an artist, he knew his potential early on.

“Actually, I had the skill since I was a kid ‘cause I was always drawing,” he said. “I remember we lived close to Juárez, close to the border, and I would go to my grandparents’ house, and they lived in Juárez, so I would go back over there. And when I was at my grandparents’ house, there was not much to do, but I did a lot of drawing there.”

He found his muses all around him.

“My inspiration was to paint people,” he said.

Still, it took a while for him to accept his calling.

“In high school, I did take a lot of classes in art, but there was a point where the art teacher was not really interested in teaching, so I kind of abandoned art for a while and I took a lot of mechanical drawing. And that motivated me to become an architect. But then afterwards, when I went to art school, then I decided to go into the arts instead of architect.

“That’s when I found out to be an architect, you need to be an engineer, too, and that’s a lot of math,” he said, smiling.

His path back to art also was ignited by finding the right partner.

“I moved to L.A. for several years, and then I became a machinist over there. And then we moved to Denton, Texas, and then I worked at Fort Worth at General Dynamics, doing machine work for the F-111 airplane, so I was very interested in machines, machinery,” he said.

“But then, when I married my wife (the late Ann Marie Enríquez), since I met her in high school, she knew I did a lot of artwork, and so she actually gave me a chest of oil paints, and so I started working with oil paints. And also while I was in L.A., I went to a lot of galleries and museums and that kind of motivated me to go back into doing art. And so that’s more or less how I started.”

After returning to El Paso County, he earned a Bachelor of Art in Art Education from the University of Texas El Paso.

Enríquez then found fulfillment teaching at Bowie High School on El Paso’s South Side.

His best memory of that time?

“My students. My students were, actually. I taught them a lot, but then they taught me a lot of things, too. And since I grew up in the same neighborhood that I went back to teach, I knew what they were all about, what they were going through, what obstacles they had to go through, what prejudice, what bigotry they had to go through, so that’s why I liked teaching at Bowie, at La Bowie, and also because I just liked to see their expressions when they learned that they had some kind of talent to continue working in art.”

Those students are what he sees as his biggest impact.

“My legacy is going to depend on who gives me my legacy or by what I have done, but in my personal view, my legacy is going to be my students,” he said.

Enríquez had to give up oil paints because he became allergic to the solvents in them, which led to sinus problems.

Painting in oil “was my favorite thing to do, because how it blended, because it didn’t dry very fast.”

When he turned to acrylics, which dry quickly, he chose to use an airbrush to continue to blend them, which can’t be done with a brush, he said.

“Of course, that was a lot of practice, practice, practice, to get the effects that I work with now.”

Still, he doesn’t miss working in oil.

“No, I think I accomplished my objective with the airbrush.”

In those early airbrush days, Enríquez also painted lowriders and murals.

But he doesn’t think any of the lowriders’ owners are wishing they still had his work on their vehicles.

“I don’t think so," he said. "Back then, I wasn’t as skilled as I am now.”

Returning home to El Paso County

Enríquez seems to accept his return to the El Paso area as a natural progression.

“Well, this is where I was born and I was raised,” he said.

But making his home in nearby San Elizario led him to a new adventure.

“My late wife’s grandmother lived here, and so we came back to help her, because she was very elderly, and since then we stayed around.”

Living in the historic area, with its many adobe structures, fueled a goal of restoring the community to its past glory.

Building a life in San Eli led him to master another craft.

“We used to live in an adobe house in El Paso, but I was too young to know about adobe,” he said.

“But the house we live in is all adobe and I restored it, and so I had to work with adobe and then restoring all these buildings here, I had to learn about adobe and how it worked.”

He read up on adobe in publications from New Mexico: “I read all about adobes, how to make them, what they do, and all that stuff.”

The yearslong effort, which required hundreds of thousands of dollars in investment, resulted in a historic, restored adobe treasure.

“It was expensive. It was a lot of work and a lot of time,” he said.

But “they are my buildings.”

And anyone who sees the result will know it was worth it.

Exhibit at the Las Cruces Museum of Art

Through May 6, art lovers can see his work at the exhibit, “Gaspar Enríquez: Chicano Pride, Chicano Soul,” at the Las Cruces Museum of Art, 491 N. Main St.

Enríquez, whose work has been exhibited across the country, said it’s the first time he’s work has been exhibited in Las Cruces, where he earned a Master in Metals at New Mexico State University.

“I have exhibited in a lot of places in the country, but I have never exhibited in Las Cruces, so that was …,” he said, his voice trailing off.

“What is that saying? That the prophet is never recognized in his hometown until he is recognized all over the world?” he said. “And that’s what happened to me, and I’m sure it happens to a lot of artists, too, or individuals that become successful throughout, somewhere else, and then they are recognized in their own environment, in their town, and that’s what happened to me.”

Now, he supports emerging artists.

“I collect a lot, if you see around the gallery here, I collect a lot of artists that are coming up. I try to help them by buying some of their work.”

Aside from tiles with portraits by Enríquez ($45) and high-quality giclée prints ($150), prices aren’t posted in the gallery.

“Well, if a person is really interested in one of the pieces, they can go get the prices from the young lady over there, but it is my preference not to put prices on the work,” he said.

Enríquez continues to create portraits by commission but said it’s difficult for him to generalize about the cost.

He said his plan to bring more people to San Elizario includes events in the spacious area behind his buildings, after the winds calm down in spring.

Attracting more visitors, tourism to San Elizario

Sharing the area’s history, beauty and importance is important to Enríquez.

“I would like to have more people, because there’s a lot of people from El Paso who have lived their lives over there, but they don’t know that San Elizario exists and what we have here,” he said.

“We have a different environment that is probably like Santa Fe,” he said, explaining how the Spaniards built structures in the Lower Valley before spreading northward into New Mexico.

“This structure here was done before Santa Fe,” he said of his buildings. “Then from here, they went to Old Mesilla, and from Old Mesilla, then they went to Albuquerque and all those places, and then to Santa Fe and to Taos, but their places over there became more well known because of the people that went in there.”

Once wealthy residents decided to live in and support Santa Fe, and an ordinance required restoration of buildings to remain true to the original structure, the status of Santa Fe as a place to live and visit increased.

Enríquez wants people to understand they can appreciate the beauty of the Southwest and its adobe buildings in San Elizario. Getting more people to visit is important, “so that they can recognize that we have a beautiful place here.”

What to do at Gaspar Enríquez's San Elizario site

Micasa Art Studio and Gallery at 1456 Main St., in San Elizario, is a brilliant example of what can be done with love, dedication and hard work. The art by Gaspar Enríquez and other artists, mostly from the Borderland, is shown in a stunning setting that transcends the gallery experience and lifts it to almost a museum quality. The gallery is open from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For disabled access, take the path to the left of the building to the final double doors on the side and knock. A sign on the front door recently said masks were required to enter, but that is no longer the case.

The Otomi Mexican Boutique at 1498 Main St. in San Elizario is open from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Friday, Saturday and Sunday. It features fashion, often with a handmade flair, and other items from designers in Mexico. Be sure to check out the pressed-tin tiles on the ceiling.

At Café Arte mi admore, 1498 Main St., you can satisfy your caffeine cravings from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Thursday through Saturday and 1:30 to 4 p.m. Sundays. Owner Erica Murrill's art is on the walls. "My specialty latte is mocha abuelita, the espresso bonbon, favorite lavender lemonade and the unique Front Porch freshly brew tea," Murrill said.

The office of state Rep. Mary González also is in the compound at 1498 Main St., in San Elizario.

This article originally appeared on El Paso Times: Gaspar Enríquez celebrates art, Chicano culture in San Elizario