Report highlights educational disparities for English learners in Savannah-Chatham Schools

A report released Monday by local nonprofit Migrant Equity Southeast (MESE) highlights the educational disparities within the Savannah Chatham County Public School System (SCCPSS) for Hispanic students and English Language Learners (ELL) and their families, communities that are rapidly growing in the region.

The study titled, “Investing in Hispanic Families in Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools,” was conducted by the NYU Metro Center, which examines and finds solutions to the problems low-income and minority students face in public education.

Savannah-Chatham Public School System officials have not yet responded to requests for comment regarding the study.

More: Two-thirds of elementary students cannot read at grade level. The district plans to fix it

More: Savannah-Chatham School touts graduation rate, but test scores, literacy rates fall far behind

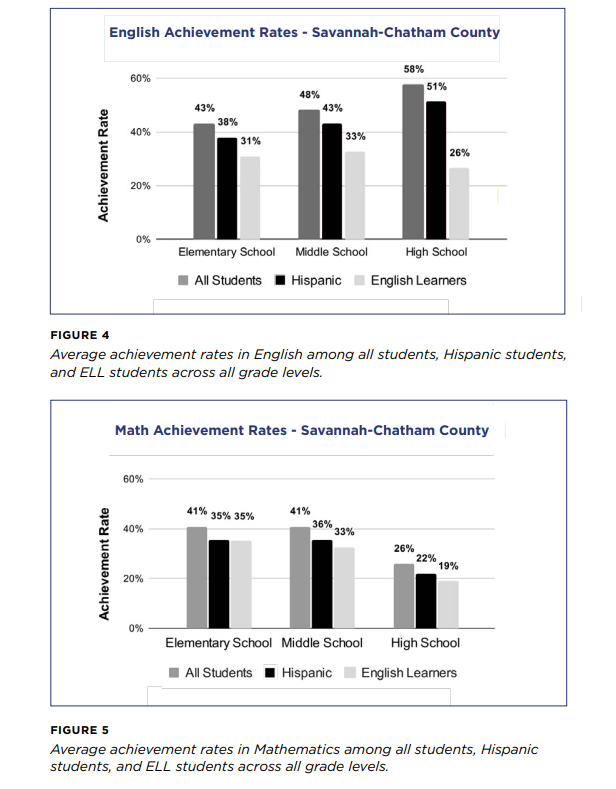

The report found that, within the Savannah-Chatham County school district, Hispanic and ELL students scored lower in math and English and graduated in lower numbers than their peers.

The findings of the report are not surprising, according to MESE members, who have listened to Hispanic and ELL families talk about the difficulties in overcoming language barriers in the school system.

“We thought it was just like a pandemic thing, that everyone was struggling and everyone was trying to adjust,” said MESE founder and executive director, Daniela Rodriguez. “But again and again, last year and through this year, we heard parents tell us about not being able to communicate with the school.”

More: Thousands of jobs are on their way to the region, are we making sure our students are competitive?

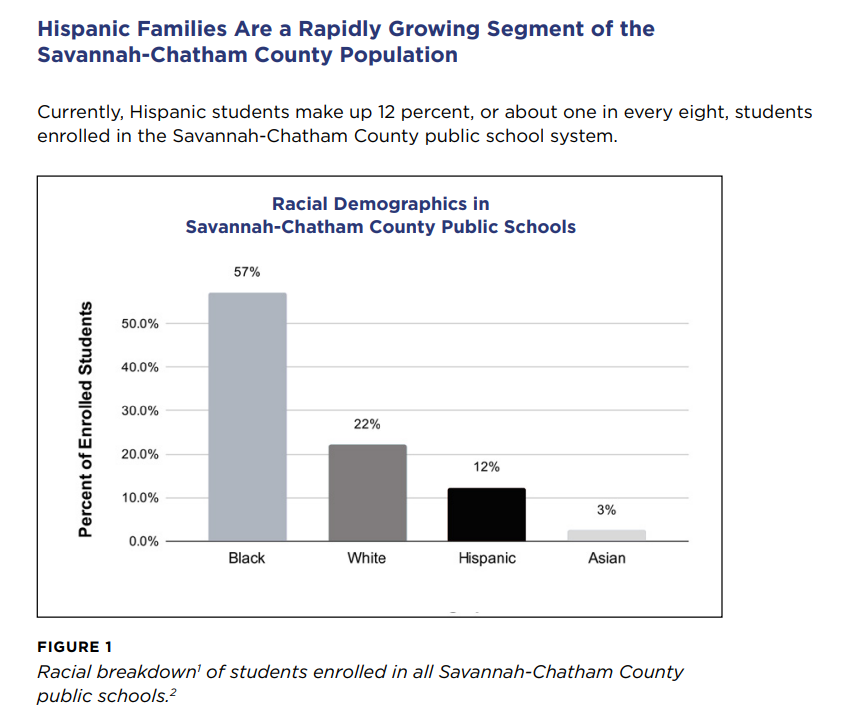

As Chatham County and the surrounding region continue to diversify, schools need to invest more in language resources to accommodate students and families whose primary language is not English, the study states. The Hispanic population is the fastest-growing group in the county and the school district. Other racial and ethnic groups, such as Asians, Pacific Islanders, American Indians, and Blacks are growing as well, though in smaller numbers.

Over the next few years, the job market is expected to expand led by hiring at major companies such as the incoming Hyundai EV plant, Gulfstream and the Georgia Ports Authority. More diverse families are already starting to move into the region, which means a greater demand for quality education with appropriate language resources.

Read the full report: "Investing in Hispanic Families in Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools"

A look at the numbers

In the last decade, the Hispanic population in Chatham County has grown by 66%, surpassing state and national growth rates (32% and 23%). The Hispanic population now constitutes 8% of the county and 12% of the school district’s student population.

The Asian population is growing significantly as well, having increased by 70% since the last decennial census. However, they constitute a relatively smaller portion (3%) of the student and county population.

Thus, Hispanic students are the fastest-growing group in the school district but face disproportionate barriers when it comes to student achievement and success, as the study shows. This is true for ELL students, as a whole, as well.

Within the district, Hispanic and ELL students scored lower in math and English achievement rates at all grade levels. Additionally, compared to the state of Georgia as a whole, Savannah-Chatham County mostly lags behind state averages in both ELL and Hispanic student achievement rates.

More: Attendance, compulsory education laws do more harm than good

At the high school level, however, ELL students in Savannah-Chatham County schools scored higher in English than the statewide averages.

English and math achievement rates were measured by students’ performance on the Georgia Milestones Assessment System and the Georgia Alternate Assessment 2.0 (the latter is an alternative assessment for students with significant cognitive disabilities).

Graduation rates for the county’s Hispanic students are slightly lower (87%) than the school district’s average (88%). Meanwhile, graduation rates for English learners stood at 69%.

The study also found that, while Black students make up a majority of the student population, they graduated at the lowest rate (85%) compared to their peers in other racial groups.

MESE, which sponsored the study, says its expertise is with Hispanic and immigrant communities, but also called for more support for Black students and students with disabilities – groups that are also underserved in the school district, according to the report.

Not enough resources for students and families

Low English and math scores and low graduation rates are evidence that Hispanic and ELL students need more support, the study states. There are not enough resources, such as educators and language programs within the school district, to accommodate the growing Hispanic and ELL student population.

In Savannah-Chatham County, 7% of enrolled students have limited English proficiency, yet only 4% of students (1,415) are enrolled in ESOL programming, according to Georgia Governor’s Office of Student Achievement.

MESE’s Alejandro Del Razo works as a community organizer and has helped translate for Spanish-speaking families within the school district.

“There are not enough teachers who are ESOL and there are not enough administrative people who can help create a more reliable system,” said Del Razo.

Del Razo said he’s spoken with parents who have moved their child to a school with better ESL programs or resources, but that puts a strain on the family in terms of transportation.

“Because some schools don’t have ESL programs, families need to send their children to schools far away from their home or, in other cases, they need to move,” said Del Razo. “So, the kids need to get up early in the morning to get ready. Another issue is that this is pushing families to a certain (geographic) area.”

The school district has made moves to improve its language resources. In the last two years, SCCPSS has hired more diverse teachers and was the recipient of a new U.S. Department of Education grant to improve literacy among English Language Learners.

But the need for more support is still outpacing available resources.

The dearth has put a strain on teachers and administrators as well. The study found that the small number of bilingual staff who were available were “overworked, overstrained and exploited.”

Oftentimes, bilingual staffers were asked to work outside of their job description, translating on phone lines and in the front offices. In some schools, faculty have even pulled custodians to help with translation needs.

“Parents want to know how their child is doing in school, but it’s hard for them to communicate with teachers because the school doesn’t have someone who speaks Spanish or doesn’t have enough translators,” said MESE’s Rodriguez.

This is true for Lisneidy Ortiz, who has a child in the 3rd grade at Windsor Forest Elementary School. Ortiz, who moved to Savannah from Venezuela with her family last year, said she's struggled with communicating with teachers and administrators because most of them only speak English.

When she received her son's report card, it was all in English, and online translations do little to help her understand the full picture of what her son is learning and how well he's doing.

"Every day there's more Hispanic people coming to this community, so if this problem isn't addressed soon, it's going to become even worse," said Ortiz through a translator.

Another issue the study points out is a lack of school counselors. The American School Counselors Association most recently recommended a school counselor ratio of 1:250. The most recent data available from National Center for Education Statistics (2023) shows that Georgia schools employ a counselor for every 419 students.

“How this affects vulnerable student populations, especially ELL students, can have detrimental effects on student achievement,” the study writes.

Burden shifts to students, families, outside groups

Most school materials are sent home to parents in English, and when it is translated into Spanish, the translation is sometimes hard to understand, Del Razo said. This makes it difficult for families to accomplish even basic tasks like registering their children for school or enrolling in lunch programs.

The language burden is then shifted to children and their parents. A survey of 154 Spanish-speaking parents showed that more than half the time, parents relied on their children to translate school materials and instruction.

“Parents feel forced to bring someone to translate. Or, if they don’t have someone in the family who speaks English, they hire someone,” said Rodriguez, who notes that some bad actors have tried to take advantage of the situation and charge expensive fees to translate.

That’s where outside groups such as nonprofits MESE and Inspiritus, which also helps with refugee and immigrant services, step in.

Inspiritus’s Executive Director of Refugee and Immigrant Services Aimee Zangandou pointed out that the school’s language line, a phone translation service, has improved over the years. But, she says, families are still struggling, especially with written communication, so they try to fill that resource gap, whether that’s translating material or assisting in parent-teacher conferences.

“The district has been trying really hard over the last few years to accommodate the language barrier,” said Zangandou. “But there’s still room for improvement.”

The language issue goes beyond the Spanish-speaking community. Inspiritus has worked with many Middle Eastern and African communities over the years. Most recently, the nonprofit has helped Ukrainian families settle in the area. Languages that these families speak include Farsi, Pashto, Urdu, Swahili, French and more, said Zangandou.

As the region continues to diversify due to economic development and immigration fueled by global crises, more language inclusion is needed.

Holistic solutions needed

The lack of linguistic access has made school life difficult for ELL students and their families. It affects students' grades, test scores and, ultimately, graduation rates. Parents are left without guidance to address student-centered issues such as absences and bullying.

MESE’s survey of Spanish-speaking parents found that most felt alienated by the lack of support from the school district. Parents were left waiting on phone lines and most school materials are only available in English. Almost half of the parents surveyed did not know what the Parent-Teacher Association was or how they could be involved in their child’s education outside of mandatory parent-teacher conferences.

Some parents surveyed said they experienced a lack of cultural sensitivity and, at times, outright discrimination.

“Parents explained that some teachers made minimal efforts to make sure students felt safe and valued for their cultural differences. If bullying occurs based on differences of culture, some teachers approached the situation with efforts to connect and guide the class towards acceptance, while other teachers did not,” the study stated.

Laura Alvarez from Garden City Elementary detailed how her son’s autistic needs went unmet and how he experienced bullying from his peers. But, because of language barriers, she struggled to find recourse for her son and took him out of school.

"They look at you and just because you're Hispanic, they treat you different," said Alvarez.

The study writes that linguistic and ableist discrimination intersect with each other and "exemplifies a clear race, ethnic, and immigrant form of exclusion."

MESE recommends that the school district take a holistic approach to address the language barrier. In addition to hiring more teachers, counselors and social workers, the district needs to invest in culturally sensitive family engagement, the study recommends.

That can be done through one-on-one conversations to build trust and mutual understanding between parents and school administrators. MESE also points to other school districts that have robust multilingual programs.

For example, the Atlanta Public School System (APS) uses WhatsApp groups to keep families informed about school updates in their home language. The Pharr-San Juan-Alamo Independent School District in Texas offers parents GED courses and English language classes.

“We are advocating for more funding, not only for the ESOL program but also for language equity so that parents are able to communicate with teachers,” said Rodriguez, “So immigrants parents aren’t lost on what’s going on in their kids’ education.”

According to school district officials, some of those initiatives are already in the works. At an informational session geared towards Korean families moving to the area for work at the Hyundai plant, Deputy Superintendent, Bernadette Ball-Oliver, detailed the district's plans to improve language resources.

This summer, the district plans to open an English language center for parents whose primary language is not English and who need help navigating the school system, such as enrolling their children in school and extracurricular activities. According to Ball-Oliver, parents will be able to enroll in ESL lessons at the center on weekends and administrators will help refer parents to wraparound services there as well.

Nancy Guan is the general assignment reporter covering Chatham County municipalities. Reach her at nguan@gannett.com or on Twitter @nancyguann.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Report shows inequities for English learners in Savannah-Chatham schools