He reported being assaulted by Minneapolis police. No one investigated.

Idrissen Brown says he was sitting in his Minneapolis apartment watching a movie with his girlfriend when he heard pounding on the door. It was about 3:20 a.m. on a Sunday in March 2016 and the couple wasn't expecting anyone after returning home from a night out.

They opened the door and found four Minneapolis police officers who said they were responding to a call from a neighbor about a domestic dispute.

What happened next, Brown said, still torments him four years later.

One of the officers grabbed him, threw him down the stairs and forced him into a squad car with another officer, Brown said. Instead of taking him to jail, Brown said, the cops brought him to an alley and pummeled him before dropping him off near his mother's house.

“When they turned the opposite direction of the jail, and he opened up the backseat and started to beat me some more, I thought I was going to die,” Brown said. ”I thought it was over.”

A few hours after he returned home, dazed and bruised, Brown said he called his local police precinct to file a formal complaint. He said he explained the entire incident to the woman on the phone and was told to call internal affairs, which he did.

Brown said he received a letter in the mail saying his complaint would be investigated. After some time passed, he said he called back and left voicemails but never got a response and eventually gave up.

“It felt like there was nothing I can do,” he said. “I felt like nobody cared.”

Brown’s complaint is on file with the Minneapolis Office of Police Conduct Review, which handles civilian misconduct complaints against law enforcement, but it was never investigated, according to police documents obtained by NBC News in a joint investigation with Minneapolis affiliate Kare 11. Instead it was labeled an “inquiry.”

The review office says complaints are labeled as "inquiries" when they are not in writing, when an investigator needs more information but can’t get in touch with the complainant, or when the person is reached but declines to cooperate.

Minneapolis police officers have been the subject of 2,034 misconduct complaints since 2016, but NBC News found that there have been an additional 791 "inquiries" in that time period — making up 28 percent of the total number of citizens who contacted the review office to file a complaint.

“Twenty-eight percent is a very high percentage,” said Susan Hutson, director of the National Association for Civilian Oversight in Law Enforcement, a nonprofit that works with agencies to establish and improve oversight in their own departments.

“The devil is in the details. Why is this occurring? Are people abandoning the process? Do they just not feel safe? But that is a statistically significant amount and you would want to know why.”

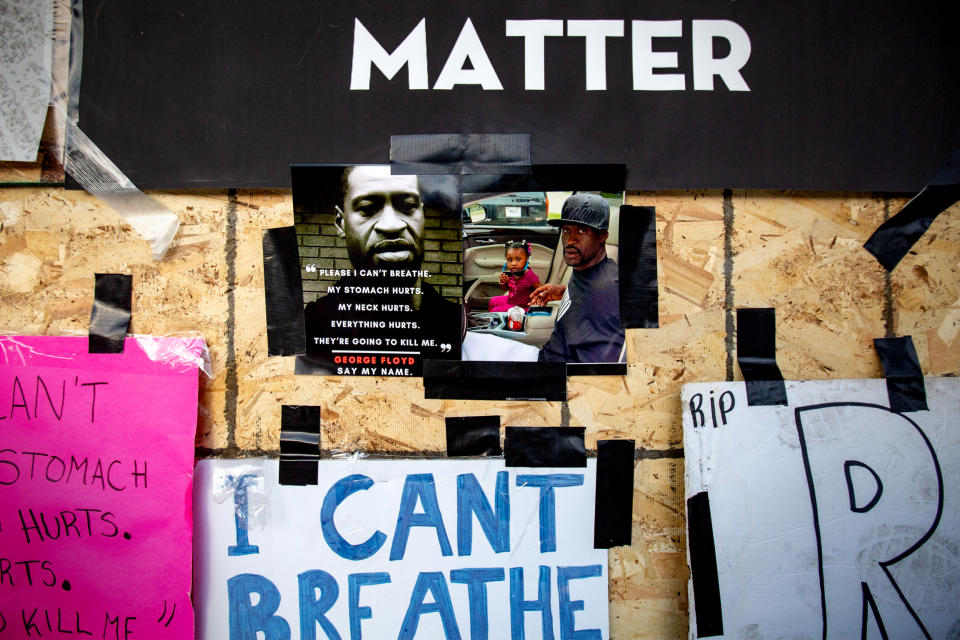

NBC News spoke to 50 people whose complaints about Minneapolis police officers ended up being classified as inquiries. They involved a variety of issues including excessive force, inappropriate behavior and unwanted injections of ketamine, a sedative. The death of George Floyd on May 25 sparked an increase in inquiries. Of those interviewed by NBC News, five were related to the Floyd case and one was about an issue at a protest that followed his death.

Twenty-three of the 50 said they received no response at all. Of the other 27, some said they were told to file a complaint in person and decided against it because it was too big of a hassle or they feared a face-to-face encounter soon after having a bad experience with the police.

Six said they received a call back asking for clarifying information but never heard from the office again. Four said they received a letter in the mail saying the complaint was not going to be pursued.

Floyd's death has focused attention on the complaint histories of the four officers present at the scene and the challenges in firing problematic cops. But the NBC News review of Minneapolis misconduct complaints suggests that the filing process is difficult and unclear and that a large number are going uninvestigated.

“I listened, and we did what we were supposed to,” Brown said. “And nothing happened.”

Andrew Hawkins, chief of staff of communications at the Minneapolis Department of Civil Rights, which oversees the police conduct review office, declined to comment on Brown’s case, citing privacy rules.

But he told NBC News that inquiries are typically followed up with two phone calls and a letter or an email. If the recipient does not respond, the department cannot proceed. Hawkins also said that phone calls are not treated as official complaints because complaints require a signature.

The police review office staff “clearly communicates to members of the community who call the office that they will need to file an actual complaint for it to be processed by the office,” Hawkins said.

But 18 of the 27 people who filed complaints by phone and spoke to NBC News said they didn’t recall being told about the signature requirement.

Even when a complaint is investigated, discipline is rarely administered in Minneapolis. Since 2016, there have been 2,034 misconduct complaints against officers in the Minneapolis Police Department. Of the 1,690 closed complaints, 23 officers, or 1.3 percent, were disciplined, a percentage considered low by Hutson.

Hawkins said the majority of the complaints involve lower level violations and do not require responses categorized as discipline. The responses include coaching and training.

Dave Bicking, a former member of the Civilian Review Authority, a prior iteration of the Office of Police Conduct Review, said he’s long been troubled by the police department’s oversight process.

“We have been in contact with a number of people that have filed complaints with the OPCR, and universally find out that it's very hard to get through and actually file a complaint,” said Bicking, who is now a member of the advocacy group Communities Against Police Brutality.

A trail of neglected complaints

Civilian oversight in law enforcement has existed in some form for around 50 years. The purpose, experts say, is to prevent the police from policing themselves.

But the practice is still not widespread. Of the nearly 18,000 police departments in the United States, only about 165 have civilian oversight, according to Hutson.

“It's a much safer space for people to come in and tell us what happened to them,” Hutson said. “People get nervous speaking to the police."

The Minneapolis Office of Police Conduct Review employs two case investigators, two intake investigators, a body camera analyst and a legal analyst — all civilians.

Complaints against officers can be made in person, by phone, online or by mail, but for a complaint to be official, it must have a signature.

Other oversight departments vary in how a complaint is filed and investigated. The NYPD Civilian Complaint Review Board allows complainants to file over the phone, but they then must do an in-person interview with an investigator. Because of the coronavirus pandemic, the board is currently allowing interviews by phone. The LAPD oversight departments allow complaints to be made by phone, in person or online.

But in Houston and El Paso, complainants must fill out a sworn affidavit and sign it in front of a notary public, which Hutson says could be a disincentive to file.

The Minneapolis police review office has access to all of the police department’s systems, so investigators can obtain police reports, supplemental reports and body camera footage.

After an investigation is complete, the director, Imani Jaafar, and the police department’s Internal Affairs commander will review the file. It will then be analyzed by the Police Conduct Review Panel, which consists of two lieutenants and two civilian employees. If the panel decides the case has merit, it’s referred to the chief of police to decide on appropriate discipline.

Among those whose complaints never made it that far was Khaled Said.

In an interview with NBC News, he said he was in a park with friends in August 2016 when a group of Minneapolis police officers rushed over and pulled their guns. The officers didn’t explain why they were stopping them and eventually let them go, Said said.

“I was scared for my life,” he said. “I never had anybody stop me for no reason.”

He said he filed a complaint in person at the Hennepin County Government Center in August 2016, but the investigator told him there was nothing they could do because he had no evidence.

Latasha Kilgore said officers responded to her son's high school in November 2018 after she called police to report being assaulted by a man she knew outside the school during pickup. Her lip and face were cut open, requiring 16 stitches, but an officer referred to the injuries as a scratch and did not arrest the man, she said.

Kilgore said she walked to her local police precinct to file a complaint but never heard back. “If I would have been white, he would have went to jail immediately,” Kilgore said.

Amber Svobodny said officers responded to her apartment around July 2016 after a neighbor called 911 fearing she was suicidal. Svobodny says she had been drinking and was asleep on her couch in her underwear when the officers arrived.

She said the officers, who were all men, ogled her and made her feel uncomfortable. She said she asked to get dressed but was told no and was then hauled off to a psych ward.

Svobodny said she called in her complaint after she was released a few hours later but was told she’d need to file it in person. She said she felt too vulnerable and decided not to pursue it.

“I told my sister after, ‘This guy knows where I live,’” she said, referring to one of the officers who she says made her feel especially comfortable.

Even complaints that include photographic evidence have been neglected. Monet Auguston worked at a bar commonly frequented by police. She said a group of over 20 Minneapolis police officers came into the bar in December 2016 after what she believed was their department holiday party.

Auguston said she noticed one of the officers was wearing an “extremely disturbing, disgusting and racist sweater.”

It featured a picture of brown-skinned men in turbans burning in a fire, as Santa Claus, flying on a sleigh, drops bombs on the men below.

“HERE COMES SANTA CLAUS, RIGHT DOWN TERRORIST LANE!” the sweater read.

Auguston snapped photos of the sweater as the officer sang karaoke. NBC News has obtained the photos and identified the officer as Cory Fitch, who has been with the department for over 20 years.

Auguston’s mom, Edie French, filed a complaint — including photos of the officer and his name in the complaint — with the Minneapolis Police Department because Auguston feared she’d be fired from her job if it got back to bar management that she filed a complaint.

French said the Minneapolis Police Department responded to her complaint saying that because French was not affected by the incident, the department would not take action.

“It’s horrifying that this happened,” French said.

Fitch could not be reached, and the police department declined to make him available. Fitch's union did not respond to requests for comment.

The Minneapolis police review office could not comment or provide any information on any of these individuals because of the Minnesota Data Practices Act. The Minneapolis Police Department did not respond to a request for comment about the incidents.

An early morning call to police

NBC News obtained the police report for the incident at Idrissen Brown’s apartment via a Freedom of Information Act Request.

The report states that the caller heard a male and female screaming at each other from inside a nearby house and was afraid it would escalate and someone would get hurt. The report is partially redacted, but says the police arrived at Brown’s apartment at 3:20 a.m. and dropped him off at his mother’s house at 3:53 a.m. He was never charged.

The officers involved were identified as Bowen Barnard, Kou Moua, Shawn Woods and Nathan Dziuk. Bowen and Moua each have eight complaints against them. All of Barnard’s complaints were closed with no discipline. Moua has two that are still open. Dziuk has had two complaints and Woods has had five with one still open.

The Minneapolis Police Department declined to comment on Brown’s allegations. A spokesperson said one of the officers, Moua, is no longer employed with the department. Barnard has been with the department for over 10 years and both Woods and Dziuk since 2013.

The four officers could not be reached. The union that represents the officers did not respond to a request for comment.

The person who called in the incident did not want to be identified, but told NBC News that they heard loud arguing and feared it could escalate into violence. The caller was not sure where the argument was coming from, but believed it was an apartment in the caller’s subdivided house or a place nearby.

The person provided their address to NBC News. It’s six houses away from Brown’s apartment building and across the street.

Brown said he is not sure why the officers came to his apartment that night. He and his girlfriend — now his wife, Lilian Plant — were up late, their lights were on and their window faced the street, so he speculated that could be the reason.

Plant said she still doesn’t understand what happened that night. She said she told the officers that she was fine and that their assistance was not needed, but they still took Brown away.

After the officers whisked him out of the house, Lilian said she frantically called family and friends asking what she should do.

“I thought he was dead,” she said. “If we're being very honest, I did not think he was coming back.”

NBC News spoke to two of Lilian’s family members and one friend, all of whom confirmed being told about the incident at the time. Two of Brown’s relatives and three friends of the couple also confirmed being told the details of the incident at the time.

Two friends, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, were on the phone with Plant while Brown was with the officers. They said they came to the couple’s home a few days later and Brown had bruises and scratches on his face and body.

The Browns moved to Texas in February 2018 in part, they say, because of their harrowing run-in with Minneapolis police. Brown said he’s in therapy and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of the incident. Watching the murder of George Floyd in his home city reopened old wounds, he said.

“To this day, all I know is, I was watching the Disney movie, and I got snatched out of my house and beat up for something I did not do, and something that was not happening,” Brown said.

“I'm not too sure what their reasoning was, and still to this day, that's what terrifies me, is I don't know. And it leaves me terrified that it can happen again. And there's nothing I can do.”