Republican Cowardice Is Creating a Mess for the U.S. Military

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

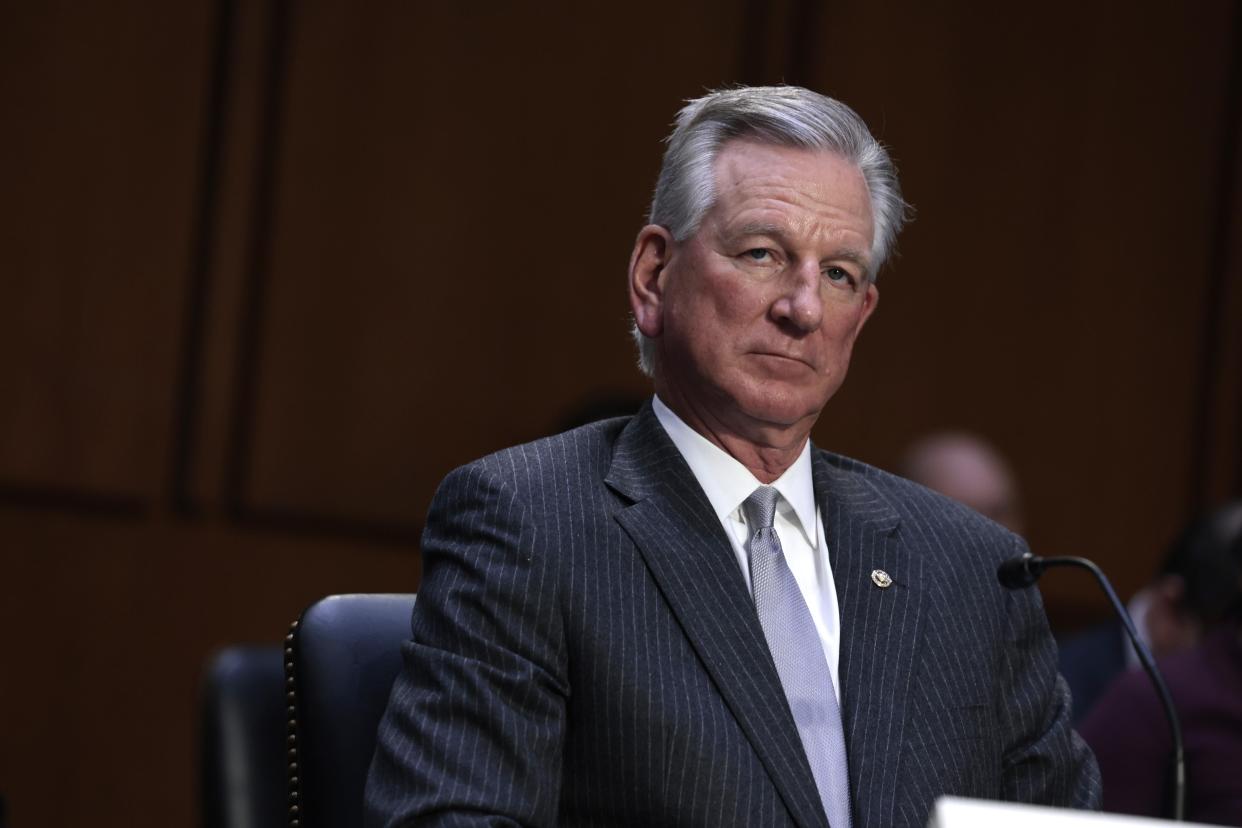

Sen. Tommy Tuberville, a first-term Republican from Alabama—a former college football coach without a lick of political experience and barely more than a lick of pertinent knowledge—is tossing the U.S. military into a rumpus unlike any since … well, nobody can recall anytime one otherwise insignificant lawmaker has unleashed such a storm.

Earlier in the summer, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin blasted Tuberville for “undermining America’s military readiness … hindering our ability to retain our very best officers, and … upending the lives of far too many American military families.”

Just this week, the civilian secretaries of the Army, Navy, and Air Force—who usually stay out of political matters and almost never take to insulting members of Congress—wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post blaming Tuberville for single-handedly “putting our national security at risk” and eroding “the foundation of America’s military advantage.”

For seven months now, Tuberville has put a one-man hold on the promotions and nominations of all senior U.S. military officers—the current total comes to 273 generals and admirals. He says he won’t drop the hold until the Defense Department drops its policy of paying for female military personnel to travel across state lines, if necessary, in order to obtain legal abortions. (The policy was put in place after the Supreme Court’s repeal of Roe v. Wade, thus allowing states to ban abortion—which 15 states, many of them the sites of military bases, now have.)

As a result, for the first time in 100 years, the Marine Corps lack a Senate-confirmed commandant. Other positions currently filled with “acting” heads—according to a list compiled by the Senate Committee on Armed Services—include the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Army chief of staff, the chief of Naval Operations, the director of the National Security Agency (who is also commander of Cyber Command), director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, the U.S. military representative to NATO, commander of the 7th Fleet and of the 5th Fleet, commander of Air Combat Command and of Pacific Air Forces, commander of the Army Space and Missile Defense Command, and superintendent of the Naval Academy.

The officers who have assumed the job of “acting” commander or director in many cases lack the legal authority to make decisions that those with Senate confirmation make routinely. On a more immediate level, dozens of officers have had to take on the responsibilities of two jobs—or to assume the jobs for which they’ve been nominated without the promotion in rank, thus forfeiting $2,000 a month or more in pay. Officers who were scheduled to move have been held in place, many with children who have left one school but can’t enroll in a new one.

As another example of the havoc being wreaked, more than 550 active-duty military spouses signed a petition to Tuberville in late July, urging him to “end this political showmanship” and “respect the service and sacrifice of those who pledge to defend this nation.”

Tuberville is able to pull this off in part because of a dumbfounding rule of the Senate—and in part because of his Republican colleagues’ cowardice.

Usually, military promotions, often dozens or hundreds at a time, are passed—first through the Senate Armed Services Committee, then on the Senate floor—in a “unanimous consent” vote. However, Senate rules allow any senator to object to this consent. When this happens, it’s usually because a senator has a problem with a particular nominee. On a few occasions, a senator has held up promotions or nominations to pry information or favors out of the Pentagon. Charles Stevenson, a former Senate aide who now teaches at Johns Hopkins University, recalled that Sen. Harold Hughes, his old boss, once blocked 6,000 Navy and Air Force promotions for a few weeks until the Pentagon released information that he and other Democrats had requested on the Vietnam War. Other senators have blocked nominations until the Pentagon restored funding for a local weapons project or base.

“Usually,” Stevenson told me in an email, “these senators get something they can call a win or back down because their colleagues pressure them quietly.” The exercise is usually kept private, and it’s all over, one way or another, in a matter of a few days or weeks. Tuberville’s drama, on the other hand, is public; it concerns a big social issue; and it’s gone on for seven months, with no sign of the first-term senator relenting.

If the block persists, another 400 or more nominations could be held up by the end of the year.

Austin has called Tuberville twice in an effort to come to a compromise, to no avail. The Senate Armed Services Committee held two votes on a motion to rescind the Pentagon’s abortion policy. After it was voted down both times, the panel’s Republican leaders urged Tuberville to drop his blockade—which he refused to do. Last month, Pentagon officials testified on the legality of the regulation. In the course of the hearing, they pointed out that the Justice Department pays for prisoners to travel across state lines in order to obtain abortions, noting that it would send quite the signal to deny the same right to women who have taken an oath to fight and die for their country.

There is one way to override Tuberville’s obstruction: The Senate could call a roll-call vote on each of the 273 promotions. However, Senate aides of both parties estimate that this would take about 700 hours of floor time. Or Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer could call votes on just the nominees for the handful of senior posts. But he and other Democrats have decided not to do this for two reasons. First, it would alienate rank-and-file members of the military to give exemptions to the top brass while leaving their immediate commanders in the lurch. Second, it would create a dreadful precedent: Backbench senators would pull this stunt over and over again if they knew that that the leaders would respond by calling a handful of votes for the most high-profile officers or officials and thus lessen the damage.

Meanwhile, Tuberville is making no friends among his colleagues with these tactics. A Senate Republican aide told me, “We all agree this is something that needs to be resolved sooner rather than later.” They have avoided putting the screws on Tuberville—say, threatening to take away his committee appointments, killing some major project in his district—because they are afraid of offending the GOP base, much of which agrees with Tuberville on abortion policy, and of offending Donald Trump.

Tuberville won the 2020 primary for his Senate seat, even though he’d lived for only a short time in Alabama (his primary residence was listed as Florida) and despite a financial scandal with a hedge fund that he co-founded (his partner was indicted for fraud), entirely because of Trump’s enthusiastic endorsement. In the general election, he handily defeated the Democrat, Doug Jones, who had barely won a special election in 2017 after the Republican candidate, Roy Moore, was accused of sexual assaulting a minor.

At least some Republicans know that opposing legal abortions, cuddling up with Trump, and alienating the military are hardly the shrewdest ways to win general elections. But for now they’re choosing to ignore all the alarm bells.