Republican Florida House members vote against own bill over 'school prayer' red herring | Cerabino

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

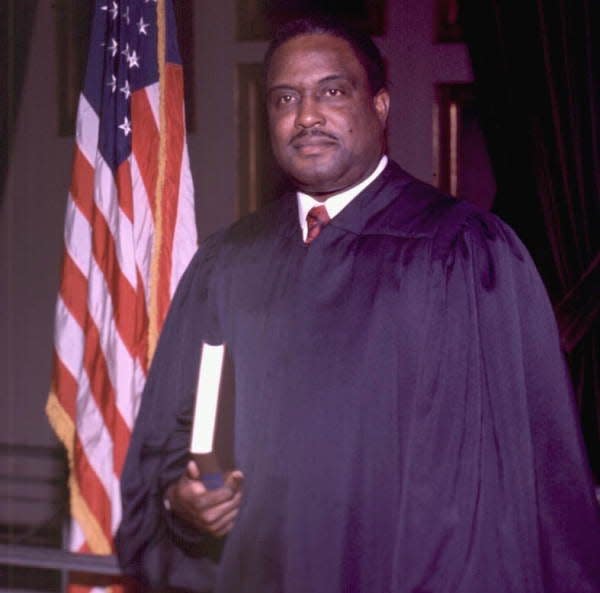

Ten congressional Republicans from Florida who had been among the 25 bipartisan House co-sponsors of a bill to rename the federal courthouse in Tallahassee after the first Black justice on the Florida Supreme Court voted against their own bill this past week, thereby dooming their own effort.

By any measure, naming the courthouse after Joseph Woodrow Hatchett, who died last year at age 88, should have been a lock.

In the U.S. Senate, both Florida U.S. senators, Rick Scott and Marco Rubio, co-sponsored the Senate version of the bill to name the “Joseph Woodrow Hatchett United States Courthouse and Federal Building” in the state’s capital.

Truth from Trump? No need to plead the Fifth: Trump heralds hole-in-one on his West Palm golf course | Frank Cerabino

DeSantis' latest villain: Out-of-state trans swimmer target of Florida governor's new dive into divisiveness | Frank Cerabino

Hitting the vulnerable: Telling it straight: 'Don't Say Gay' bill about Florida teens, not preschoolers | Frank Cerabino

Naming the building after Hatchett won unanimous support in the Senate. After the vote, Rubio issued a statement.

“Judge Hatchett lived an inspiring life of service, first as a member of the United States Army and later as the first African-American Supreme Court Justice for the State of Florida,” Rubio wrote. “His story is worthy of commemoration, and I am pleased to see the Senate pass my legislation to do exactly that.”

Judge Hatchett, trailblazing judge

Hatchett’s legal career, which began with him taking the bar exam in 1959 in a hotel where he was not permitted to eat a meal or spend the night, took him all the way to chief judge of the Atlanta-based U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, the appellate court for federal cases from Florida, Georgia and Alabama.

U.S. House members from Florida in both parties piled on to be co-sponsors of the bill to name the Tallahassee federal courthouse after Hatchett. But in the minutes before the vote, something happened to derail it.

U.S. Rep. Andrew Clyde, a Georgia Republican, circulated a 1999 opinion by Hatchett regarding prayer at public high school graduations, according to U.S. Rep. Al Lawson, a Democratic congressman from North Florida, who was sponsoring the building-naming bill.

Clyde should be an easy guy to ignore.

Clyde was one of three members of the U.S. House who voted against 422 of his colleagues in the passage of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act. And in a speech opposing the confirmation of Ketanji Brown Jackson to the U.S. Supreme Court, Clyde ventured beyond ridiculous in his hyperbole:

“As crime rates soar in our cities across the country, adding soft-on-crime justices — especially a justice who basically ignores the crime of possessing and promoting images of severe child sexual assault — adding a justice like that to the bench sends an alarming message to communities fearing for their safety.”

Oy.

Georgia congressman leads charge against Florida judge

Clyde is also the congressman who said the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol was “a normal tourist visit," even though he was one of the House members who barricaded the House doors with furniture as rioters were trying to push their way in.

He’s a serial chucklehead. And yet, raising the issue of school prayer was all it took to send Florida’s timid Republicans scurrying for job security.

“To witness on the House floor, Republican votes change in disapproval of the bill during the final seconds of roll call, was abhorrent,” Lawson told FloridaPolitics.com.

In the end, 147 Republicans settled on “No” votes, sinking the needed two-thirds majority for the building naming. The “No” votes included 10 Florida Republicans who were co-signers of the bill.

They are Brian Mast, Matt Gaetz, Greg Steube, John Rutherford, Gus Bilirakis, Vern Buchanan, Kat Cammack, Neal Dunn, Scott Franklin and Byron Donalds.

Donalds has the added dubious distinction of being one of two Black Republicans in the U.S. House.

I read Hatchett’s opinion in the 1999 school prayer case, which was styled Adler v. Duval County School Board.

It revolved around the Duval County School Board’s efforts, in concert with a local Christian pastor, to “fish” — in his words — for a way around a 1992 U.S. Supreme Court case named Lee v. Weisman.

That guiding case held that school-sponsored prayer at public school graduation ceremonies violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Duval’s legal adviser, in a memo titled “Graduation prayers,” explained to the district’s high school principals that they could get prayers at their graduation ceremonies by having them orchestrated by the graduating students, not the school staff.

“If the graduating senior class chooses to use an opening and/or closing message, the content of that message shall be prepared by the student volunteer and shall not be monitored or otherwise reviewed by Duval County School Board, its officers, or employees,” the memo suggested.

And that’s what 10 of the 17 high schools in the county did, getting prayers at graduation run through the students, not the administrators.

And that created the lawsuit that eventually reached Hatchett, who wrote that it still violated the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the Lee case:

“Our review of Lee and cases from other circuits leads us to the conclusion that the delegation of the decision regarding a ‘prayer’ or ‘message’ to the vote of graduating students does not erase the imprint of the state from graduation prayer. Further, the Duval County school system developed this policy as an attempt to circumvent Lee and continue the practice of prayer, and to permit sectarian and proselytizing prayer, at graduation ceremonies.

“We hold that the state’s control over nearly all aspects of the graduation ceremony, and the choices of a student-elected representative, subjects the ceremony to the limits of the Constitution.”

It’s not a radical opinion. And to imagine that this reasoned opinion, which followed the precedent case decided in the U.S. Supreme Court, was somehow a justifiable basis to deny honoring Hatchett and his lifetime of legal accomplishments and milestones is an act of malice.

You’d think those 10 Florida Republicans who sponsored the bill would have stood up for him.

Florida's busy history with school prayer

And yet, this act of group legislative cowardice is not out of character with Florida’s recent history on the issue of school prayer.

Over the years in Florida, school prayer has existed mostly as a political issue, with state laws being passed not to be implemented, but just to coddle to base voters.

For example, Rick Scott, who co-sponsored Hatchett’s name on the building, also signed as governor a 2012 state bill that rebranded prayers as “inspiration messages” and allowed them at public school assemblies.

“School personnel may not participate in, or otherwise influence any student in, the determination of whether to use prayers of invocation or benediction,” that law said.

The law was passed, and then was promptly ignored by school districts due to its constitutional flaws.

“We are highly recommending that no school do anything to enact this legislation,” said Wayne Blanton, the executive director of the Florida School Boards Association, which establishes policy positions for school boards across the state.

“This was just something done to give people something to talk about on the campaign trail,” Blanton said at the time. “That’s all it was.”

If put into practice, these school-prayer bills become lawyer relief acts. The taxpayers of Santa Rosa County in the state’s Panhandle paid about $900,000 to be on the losing end of a four-year-long prayer-in-school case.

But the urge to pander is strong. So the state Legislature and Scott, as governor, signed his second ignored school-prayer bill in 2017.

This one was called the Florida Student and School Personnel Religious Liberties Act.

For the most part, it pushed for protections that already exist: That students or teachers can’t be discriminated against based on their “religious viewpoint or religious expression.”

And that they can pray and organize religious activities before, during or after the school day to the same extent that secular activities are permitted.

But it got a little nutty by adding that “a student may express his or her religious beliefs in coursework, artwork, and other written and oral assignment free from discrimination.”

This was a red flag for the Florida Citizens for Science, a nonprofit education group dedicated to the idea that “the proper focus of science education is the study of the natural world through observation, testing and analysis.”

I guess this means that students can challenge their teachers on the contemporaneous existence of man and dinosaur and the six-day creation story.

Judge Hatchett deserved better

It was another imaginary issue that is directed more at adult voters than Florida’s children.

Last year, Gov. Ron DeSantis, never willing to leave a scab unpicked, waded into the school prayer issue by signing a bill that calls for up to two minutes of “silent reflection” at the beginning of the day for K-12 public school students.

And it, too, was just another attempt to shoehorn constitutionally problematic school prayer into public school classrooms. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 1985 Alabama case that imposing periods of silence in schools as a way to promote prayer is unconstitutional.

So the Florida bill dances around that in a less than genuine way. The bill reads:

“The Legislature finds that in today's hectic society too few persons are able to experience even a moment of quiet reflection before plunging headlong into the activities of daily life. Young persons are particularly affected by the absence of an opportunity for a moment of quiet reflection.

“The Legislature finds that our youth, and society as a whole, would be well served if students in the public schools were afforded a moment of silence at the beginning of each school day.”

We’re still dancing around the subject that Judge Hatchett decided 23 years ago: You can pray all you want in public school. But you can’t subject other people’s children to your prayers.

It’s pretty simple. Shame on us for electing people who are too frightened for their own careers to stand for anything more than self-preservation.

Poor Judge Hatchett. He deserved a better state.

fcerabino@gannett.com

@FranklyFlorida

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Florida Republicans vote against renaming courthouse to honor Black judge