Republicans Push to Strip Abortion Access for Veterans

Lindsay Church and their wife started planning for a family in 2021. Church, who served as a linguist in the U.S. Navy, is medically retired from the military. “I’m missing 42 inches of my ribs, all the cartilage in my chest, and I have a spinal cord stimulator that controls my pain,” Church explains. Because of those injuries, Church has always known that it would not be possible to carry their own pregnancy: “A long while back, my wife became the person that was going to have the baby for us.” The couple went through all of the prenatal testing, secured a donor, made their initial attempt to conceive in May of 2022. She got pregnant on the very first try. “That doesn’t happen very often,” Church says. “We felt really lucky.”

One month later, the Supreme Court struck down the federal right to an abortion. Two weeks after that, Church and their wife got the first indication that there might be something wrong with their baby. But they would have to wait for an amniocentesis — a test that cannot be performed until at least 16 weeks gestation — to be sure. “It was the longest month of our lives,” Church, executive director of the advocacy group Minority Vets, says.

When they returned to the doctor’s office in August, the couple received confirmation that their child had a rare fetal anomaly. “The doctor tells us their bladder can’t empty. Over the period of these weeks, their bladder and torso has gotten to the point where they’re basically filling up like a balloon because they can’t release the fluid. They had this tiny, tiny pocket of amniotic fluid that was all that they were living on at this point,” Church recalls. “They were suffocating.”

Church has a 100 percent service-connected disability, which makes both them and their spouse eligible for full health care coverage through the Department of Veterans Affairs. But at the time, in August 2022, the VA did not provide abortions or abortion counseling to the more than 9 million veterans and family members it serves. Until recently, veterans like Church and their families were forced to go out of network, pay out of pocket and, in many cases — in the wake of the Dobbs decision — leave the states where they live to receive care.

That changed in September 2022, when the Biden administration implemented a rule empowering doctors at VA facilities to provide counseling and perform abortions — even in states where abortion is banned or severely restricted. “It’s an unusual example of the federal government saying: ‘Actually, we have supremacy in this case, and we’re willing to use it,’” says Kayla Williams, who previously served as director of the Center for Women Veterans at the VA, and is now a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation.

But with negotiations for the 2024 budget underway in Congress, the policy and the access it codifies are under attack. In June, Republicans on the House Appropriations Committee advanced a budget that prohibited abortion care (and gender affirming care and the pride flag) at VA facilities. The committee’s counterpart in the Senate passed its own version of the budget without the attacks on abortion and gender-affirming care. The two budgets will have to be reconciled in a closed-door conference committee process. Advocates worried that the abortion policy could end up as a bargaining chip in that process.

There are more than 2 million women veterans of reproductive age — between the ages of 18 and 44 — using VA health care. When the rule went into effect last fall, more than a quarter million of them lived in states with significant abortion restrictions. But in the months since the policy went into effect, only a tiny fraction of that population has used it: in April, the VA reported to Congress that only 34 individuals had received care between September and February. The agency previously estimated more than 1000 would take advantage of the policy in the first year. (A spokesman for the VA declined to provide more recent data. “We are not providing numbers of procedures or locations for various reasons, chiefly for the privacy of Veterans,” Gary Kunich told Rolling Stone.)

Williams attributes the smaller-than-expected number to a failure to communicate to veterans who need it what benefits are available. “Actually reaching women veterans to ensure that they know what benefits and care they are eligible for is very hard,” Williams says. “It’s just really hard to get this information out there.”

Arguably the biggest publicity for the VA’s abortion policy has come from Republicans furious over the policy and using any means possible to force the VA to rescind it. Shortly after the rule went into effect, GOP attorneys general from 15 states sent a letter to VA Secretary Denis McDonough threatening legal action. When a VA-employed nurse in Texas later filed a lawsuit claiming the policy would force her to violate her conscience, 18 Republican attorneys general joined an amicus brief in support of her claim. (The lawsuit has not been resolved.)

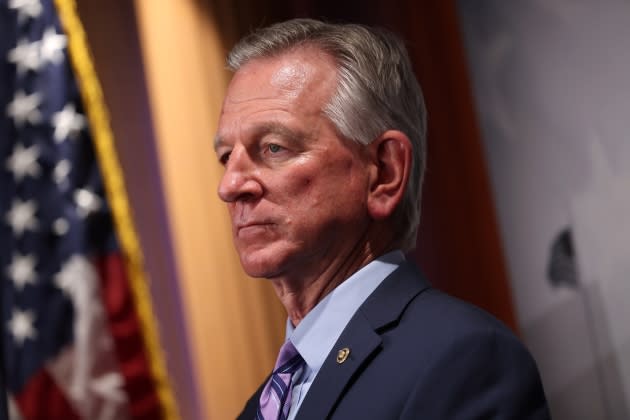

The loudest critic of all has been Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-AL). Tuberville has registered his disapproval for the VA policy, as well as another reproductive health policy governing active duty service members, by continuing to block both appointments and promotions and for hundreds of military personnel. In April, Tuberville offered a Senate resolution that would have revoked the policy. The resolution failed 51 to 48, with Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) joining Democrats to defeat it.

On a party line vote in June, Republicans who control the House Appropriations Committee inserted language into the 2024 Veterans Affairs budget that would block the VA from, in their words, “prevent taxpayer dollars from being used for abortion on demand.”

Now, as the House and Senate versions of next year’s VA budget have to be reconciled, advocates and Congressional aides worry that motivated opponents of the policy could have an outsized influence on the process. It is not a Republican, but rather a Democrat they’re concerned about. Among the VA policy’s critics is Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), who joined Tuberville in co-sponsoring a Senate resolution earlier this year that would have blocked the policy.

At the time, Manchin said the idea of providing the full suite of reproductive healthcare to women veterans would constitute “disrupting the whole operation of the VA who is responsible for the services for our veterans who have bravely fought for us and defended us. I think for them to have a quality system that works for their best care is what we should be concerned about.” Machin’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment about whether he would attempt to use the budget process to revive efforts to end the VA policy.

After learning of their baby’s prognosis in August 2022, before the VA rule went into effect, Church and their partner were on their own to seek abortion care. By the time they were able to book an appointment at an abortion provider outside the VA, their baby was no longer alive. They were nevertheless forced to navigate a gauntlet of protesters outside the clinic “literally calling us baby killers.”

Church remembers how needlessly cruel it all felt, how oblivious those people were to their circumstances. “Our baby’s dead. At this point, all you’re doing is harassing and hurting people — for what?” After that experience, Church says, “I’m on a mission to make sure that there continues to be access for veterans, servicemembers, and their families and anybody who needs it.”

More from Rolling Stone

Iowa Passes Six-Week Abortion Ban as Protesters Flood Capitol

Trump Blasts Prosecutor He Appointed for Not Giving Hunter Biden 'Death Sentence'

Tommy Tuberville Begrudgingly Admits White Nationalists Are Racist

Best of Rolling Stone