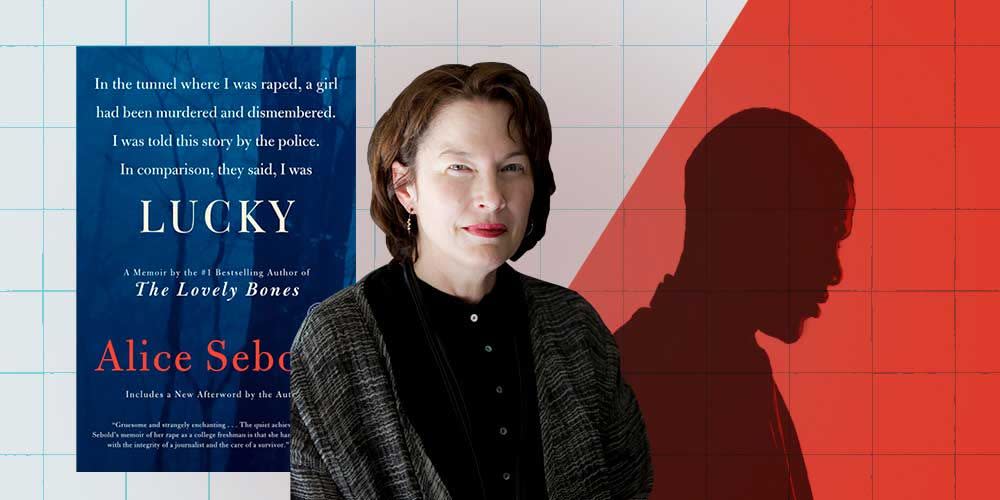

Rereading Alice Sebold’s ‘Lucky’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

While reading Alice Sebold’s 1999 memoir Lucky for the first time in about two decades, I was struck by the prevalence of apologies in the narrative. “I’m so sorry. You’re a good girl,” repeats the man, sometimes in tears, after brutally raping and beating her in a park near Syracuse University. Earlier, Sebold had been the one who “never stopped apologizing,” saying whatever it would take for her to survive the attack. And in other instances in the book—when she identifies the wrong man in a lineup, or gets tripped up in cross-examination—Sebold seems set upon apologizing to those she feels she let down.

As we now know, the person most let down was Anthony Broadwater, the man whose conviction for Sebold’s May 1981 rape was overturned in late November, more than 20 years after the end of his prison sentence. This shocking turn came about after the court reconsidered Sebold’s eyewitness account, which initially identified a different man, and a now-discredited hair analysis linking Broadwater to the crime. The result probably never would have happened if Timothy Mucciante, a one-time executive producer of a since-abandoned film adaptation of Lucky, had not begun his own independent investigation.

Some of the apologies in the book (recently pulled from circulation by its publisher, Scribner) are genuine. Others are more performative. Sebold’s most recent apology, given in a Nov. 30 statement, seems to inhabit both states, owing perhaps to extensive legal vetting before its release. “I am sorry most of all for the fact that the life you could have led was unjustly robbed from you, and I know that no apology can change what happened to you and never will,” Sebold writes. Broadwater, who burst into tears upon seeing the statement, told the Syracuse Post-Standard: “It comes sincerely from her heart. She knowingly admits what happened. I accept her apology.”

Apologies, however, merely begin a new chapter of a story that encompasses a brutal rape, a mistaken eyewitness identification, unconscious racial bias, a best-selling memoir, and now, a wrongful conviction. (Mucciante, for his part, is at work on Unlucky, a documentary about the Broadwater case.) What happens when one sets out, as Sebold did, to transform trauma into literature—and the foundation turns out to be utterly wrong?

Memoirs are governed by the idea that subjective truths can stand in for more universal perspectives. True crime memoirs take this idea to a greater extreme, as writing about the worst thing that has happened to you—rape, the murder of a loved one, or some other horrific type of violence—offers broader meaning for those who have survived similar events, and those wishing to understand how it’s possible to survive them.

In its first hundred pages, Lucky succeeds as a first-person chronicle of brutality and its aftermath. As harrowing as it is to read about Sebold’s hours-long sexual assault in Syracuse’s Thornden Park, it is yet more sickening to encounter her father’s unthinking callousness (“If it had to happen to one of you, I’m glad it was you and not your sister”), a female therapist’s indifference (“I guess this will make you less inhibited about sex now, huh?”), and a police officer’s blithe attitude toward major errors in Sebold’s affidavit about the rape: “All of that doesn’t matter,” says the officer. “We just need the gist of it. As soon as you sign it, you can go home.”

That line now lands with the jolt of a key twist in a horror story, which Lucky transforms into as soon as Sebold spots a young Black man “talking to a shady white guy” on the street more than five months after her assault. She can only see his back, but hyperawareness kicks in: the height, the build, the posture aligns with her memory. Later, she notices a policeman exiting his patrol car. “As if out of nowhere,” writes Sebold, “I saw my rapist crossing toward me.” He is smiling. She thinks he recognizes her. And then, she remembers him saying: “Hey, girl, don’t I know you from somewhere?”

Except, as Sebold herself learns 15 years after the fact, Broadwater (called “Gregory Madison” in the book) was addressing the police officer. It’s unclear if he ever said the words “hey, girl” or if Sebold thought she heard them, caught in “a more intense version of the fear I had felt around certain Black men ever since the rape.” But because of her certainty in that moment, it affects everything to follow, including the crushing disappointment she feels at failing to identify Broadwater as her rapist in a police lineup: “A panicked white girl saw a Black man on the street. He spoke familiarly to her, and in her mind she connected this to her rape. She was accusing the wrong man.”

From there, Lucky becomes a vertiginous roller coaster. Because the reader knows Broadwater has been cruelly wronged, every instance of Sebold trying to bolster her confidence only augments the wrongness. Her hatred of Broadwater’s lawyer seems irrational when he’s trying to identify inconsistencies in her story under cross-examination. The prosecutor’s insistence that Broadwater and a friend conspired to rig the lineup turns out to be a lie. And Sebold’s discomfort when thinking or talking about race (“this wouldn’t be the first time, or the last, that I wished my rapist had been white”) instead of affording her sympathy, only worsens the damned inequity of being Black in the American criminal justice system.

There are more shocks in store even after Broadwater is convicted of raping Sebold based on faulty identification and junk science. Two years later, Sebold’s roommate Lila is raped—and it takes place in Sebold’s bed while she is out. Lila decides not to pursue charges, wanting to move on with her life. But police tell Sebold that they believed Lila “might have been raped out of revenge.” The rapist, apparently, knew Sebold’s name, her school and work schedule, and more. “Conspiracy seemed a stretch to me,” she writes.

When we know how certainty and memory has failed her, can we really trust that this appalling crime happened by mere coincidence, or that it even happened as she described? Sebold’s writing teacher at the time, Tobias Wolff, had instructed her to “remember everything.” What she remembered sparked a tragedy that even adequate compensation can’t properly fix.

“I live in a world where the two truths coexist, where both hell and hope live in the palm of my hand,” Sebold writes in the closing lines of Lucky. As a result of Broadwater’s overturned conviction, those truths have cleaved apart. There can be no reconstitution of the story as it was, because Sebold’s narrative, placing herself at the center, no longer holds.

Lucky, should it return to circulation, cannot merely slap an afterword with updated events at the end of a new edition. It requires a wholly different frame, one that pulls back the curtain on unreliable memory, lazy and ineffectual policing, tunnel-vision prosecution, and the fact that Sebold—despite the unspeakable harm perpetrated upon her in Thornden Park that May night in 1981—actively participated in a system that perpetrated an altogether separate unspeakable harm upon Anthony Broadwater.

That Sebold apologized in her statement, and Broadwater accepted the apology, is a start. But if Lucky is to remain true to its aim of finding broader meaning in a singular story, then any new version has to consider that Broadwater’s wrongful conviction stands in for thousands of others, and that Sebold’s 40-year certainty that she identified the correct man also stands in for the dangers of believing oneself to be a reliable narrator in a system designed to reward white women’s tears.

You Might Also Like