Rescue in Albania: How an RI Guard aircrew plucked avalanche survivors from mountainside.

The online "NOTIFICATION!" was posted by a European mountain rescue service operating in Albania. Its tone was urgent.

High in the mountains of Albania's Korab range, near Kosovo, rescuers were trying to save the lives of two Swiss skiers who had suffered long hours trapped in the heavy snow of an avalanche. The two survivors, a man and a woman, were in stable condition, according to the social media post.

But they showed symptoms of hypothermia, and their rescuers suspected they had broken bones. And while they were no longer trapped in the snow, and they were in the company of a rescue team, the two avalanche survivors remained stranded.

The rugged mountain terrain has "made this … very complicated," said the Kosovo Mountain Search and Rescue Service's online notification, which was posted in the predawn hours of Jan. 22.

"We will notify you" of developments, the post added.

The mountain rescue service hoped daylight would bring a helicopter evacuation operation directed by the Albanian government. The chopper, threading its way between peaks and over ridgelines, arrived as hoped after sunrise that morning. But the pilot couldn't find a safe landing spot.

"A plan B had to be made," the rescue service concluded. They needed a helicopter that could retrieve the two avalanche survivors from the mountainside without landing – a chopper with a hoist.

The idea wasn't far-fetched: A U.S. Army Black Hawk helicopter with that capability was just over Albania's border in Kosovo at a base named Camp Bondsteel. The helicopter's aircrew, a team from the Rhode Island Army National Guard, was on duty, awaiting their next rescue mission.

And they knew how to use a hoist.

'Butcher of the Balkans'

A wave of ethnic conflict in the region more than two decades ago is responsible for the continuing presence of U.S. troops in Kosovo. The NATO-led force they serve, Kosovo Force, or KFOR, was established after a bombing campaign forced a withdrawal of federal Yugoslavian troops and Serb forces in 1999.

Their leader, Slobodan Milosevic, was accused of war crimes. A tribunal charged Milosevic in the deaths of hundreds of Kosovo Albanian men, women and children.

Taking aim at 'Sloba'

Milosevic, who went by the nickname Sloba, was a demagogue who exploited ethnic and religious conflict for his own political gain. He was accused of trying to secure Serb control over the region through the deportation of about 800,000 civilians and by carrying out a campaign of fear that involved mass rape and other means.

His prosecution, before the United Nations' International Court of Justice, ended after he died inside his cell at The Hague in 2006.

But KFOR remained at the forefront of NATO's efforts to support peace and stability in Kosovo.

Last May, just before Rhode Island Guard troops deployed at Bondsteel, clashes between police and ethnic Serbs in northern Kosovo elevated tensions in the region, according to the Associated Press.

In neighboring Serbia, the AP reported, President Aleksandar Vucic said he had put the army on the “highest state of alert” and ordered an “urgent” movement of troops closer to the border."

Task Force Rogue arrives in Kosovo in 2023

Soon after these events, Rhode Island Army National Guard members in the 1st Battalion, 126th Aviation Regiment, formed Task Force Rogue at Bondsteel last June.

Many of them continued to enhance their hoist qualifications, recalls Rhode Island Army National Guard Capt. Mark Dente, who corresponded with The Providence Journal via email.

Dente, who flies Black Hawks, regards airborne hoist work as "one of the most dangerous modes of flight we do."

More: RI National guard plays a key role in Kosovo

Working with an aerial hoist

The U.S. Army requires each member of a helicopter medevac crew to receive qualification on the equipment, according to Dente.

And to stay current, Guard members must operate the hoist at least once every 90 days, Dente says.

Since their arrival, in addition to such training, the Guard aircrews have completed 17 medevac missions, mostly involving KFOR soldiers, Dente says, with the medevac patients' medical issues ranging from heart trouble to traumatic injuries suffered in motor-vehicle crashes.

Generally, says Dente, two pilots, a crew chief and a medic fly on each mission.

The aircrews tote radios that alert them to medevac missions.

Medevac operations for KFOR

"We always have two helicopters ready to launch," Dente says. Each crew is on call for 48 hours.

During the first half of its shift, a crew backs up another crew. If the "1st Up" team is handling an emergency, the backup crew handles the next emergency call.

During the second half of the shift, the "2nd Up" team moves to "1st up," which means they are ready to fly out within 15 minutes of when the command post receives a call.

Seeking out ski slopes in an Albanian avalanche zone

On Sunday, Jan. 21, two skiers began a mountain ascent in their ski boots, climbing in an area just northeast of the top of Sorokoli Mountain, according to the mountain rescue service.

Sorokoli, which is in front of Korab Mountain, rises to almost 8,000 feet above sea level, according to a local mountain tour operator.

As the Swiss skiers climbed, they set off an avalanche that swept them more than 1,000 feet down the mountain, according to the mountain service's social media post.

Hamas ruined the wedding of an Israeli man with RI ties. How the groom responded.

They were not entirely buried in the snow, but they were stuck. The young woman had enough mobility with her hands to declare an "SOS" with her cellphone, according to rescuers.

The rescue service says it learned about the avalanche late on Jan. 21 from local residents who placed emergency calls. Later, the service made contact with one of the survivors via cellphone, securing the map coordinates of their location, says a post.

A small contingent, aided initially by police, set out on a nighttime search and rescue mission, the service's news release said. Hours later, two rescue specialists and a paramedic found the avalanche survivors in the darkness.

Mountain landscapes and a helicopter rescue

Task Force Rogue learned about a special request from Albania around 10:45 the next morning, well after the initial sunrise helicopter mission.

The mission, which might involve a hoist, awaited approval higher up the command chain. Dente, the team leader, and four other R.I. Guard members prepared for launch.

The team included Chief Warrant Officer Joshua Mason, also a Cranston police officer and instructor pilot; the helicopter's crew chief, Sgt. Brandon Bessette; and two flight paramedics, Staff Sgt. Ryan Farley and Staff Sgt. Matthew Medeiros. They had plenty to think about.

The Korab range

They assessed issues ranging from the performance limits of their New England-built Sikorsky helicopter to the number of people they would evacuate, which governed medical supplies.

Dente says the team pulled up satellite images to scout the site where the survivors waited.

Mason determined that the site was in a trough-like topographical feature just below a mountain peak that poked up about 7,200 feet from sea level. Nearby, Korab Mountain, Albania's tallest peak, rose up another 2,000 feet.

High-altitude helicopter horsepower

Dente and Mason made various calculations related to how much power they could expect from the Black Hawk at such heights.

The weight of the helicopter, including the load it was carrying, would play into it. Air temperature was another factor. So was fuel consumption.

Dente placed the rescue zone about 50 miles southwest of Bondsteel. Flying there would take 20 to 25 minutes.

"We received a weather brief that the conditions should generally be calm," Dente says. "It was a clear day, and the weather wasn’t expected to degrade until way later in the evening."

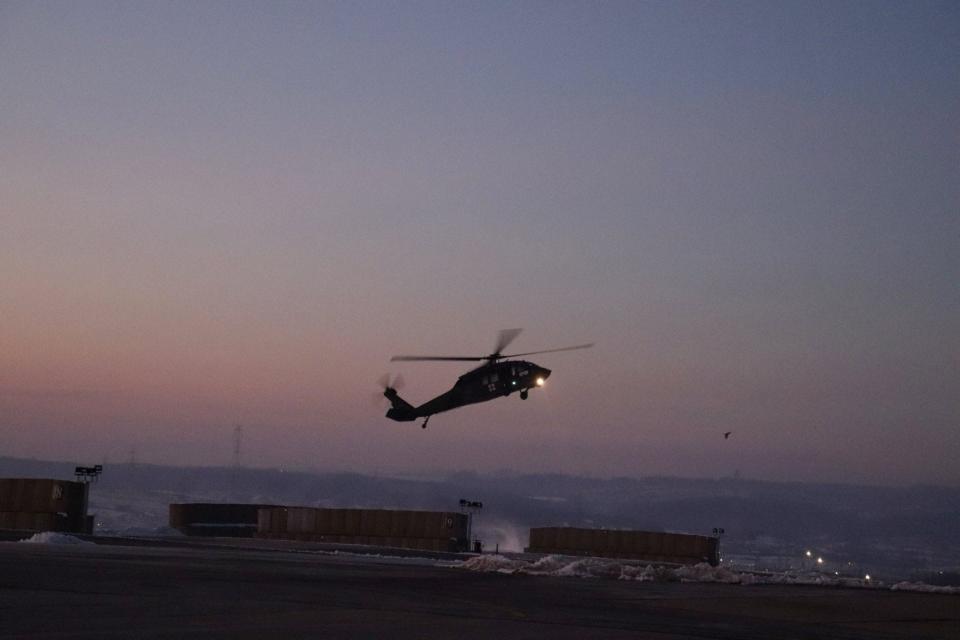

The commanding officer of KFOR, Maj. Gen. Özkan Ulutaş, authorized the flight. Loaded with extra blankets and heat pads, the UH-60 twirled into the air at 12:37 p.m. Dente, Mason and the crew hoped to lower the helicopter to ground level for a simple pickup without any hoisting. They could also set the chopper down on just one wheel, a pinnacle landing, if necessary.

"We owe it to the patient to extract them in the easiest and most efficient way possible," Dente says.

While the Guard members' consistent, all-seasons hoist training had inspired confidence, none of them had previous experience lifting a medevac patient into a helicopter from an unknown location, Dente says.

Rescuers wave from avalanche zone

As the R.I. Guard members hovered over the snowy rescue site in their sleek aerial ambulance, Dente and Mason concluded that touching down, even on just one wheel, wasn't possible. The pilots saw no other suitable landing zone nearby.

Medeiros descended on a line to the mountainside, bringing hoist straps and a Sked rescue stretcher. He found the two Swiss alpinists accompanied by seven rescuers from the mountain service and two police officers. Some were uncertain about their ability to hike off the mountain after many hours of severe winter exposure.

Medeiros triaged the two avalanche survivors and prepared them for the hoist.

The Black Hawk hovered above with its engines on a setting for endurance.

The hoist operator, Bessette, wore latex gloves underneath flight gloves for better dexterity in his hands.

The mountain extraction of both avalanche survivors was "very smooth," Dente says.

By the time Medeiros was back aboard, the Black Hawk had been at the site for more than 30 minutes.

To stay on schedule for fuel use, the team had to leave, recalls Dente, who led the medevac team.

They would refuel and return to rescue the rescuers.

Less than 25 minutes later, they descended toward a hospital helipad in Tirana, Albania. A large group of people crowded the landing zone.

The two medevac patients were carried away in rescue stretchers. In time, they would visit with an Albanian government official. But the KFOR medevac team had more work to do: The crew flew to a nearby airport to refuel. Then they returned to the mountainside avalanche zone.

The situation had changed: Fewer rescuers were visible on the ground. Assessing their emergency needs proved difficult. After some confusion, and a good deal of flying, the helicopter aircrew hoisted two rescuers from the original site and flew them to a slope near their snowmobile.

"Every person did their job, executed the mission, all without hesitation," Dente would recall afterward.

Sunset was about 20 minutes away as they flew back to their base.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: US National Guard rescues avalanche survivors from Albanian mountain