He’s rescued 900 buildings to save NC history. Meet the N&O’s Tar Heel of the Year.

In a scene near the beginning of the 1997 movie “Titanic,” our heroine, Rose, peers out of a submarine surveying the ship’s wreckage to see through the murky water the corroded, but distinctly curlicued, metal grate of the double doors once leading to the First-Class Dining Saloon.

The broken ship has sat on the ocean floor for 84 years. But instantly, in the character’s mind, it’s 1912 and a pair of white-jacketed waiters swing open the gleaming doors to welcome Rose into the elegant Louis XVI-style room with its ornate columns, arched ceiling and elaborate plasterwork, in all their original glory.

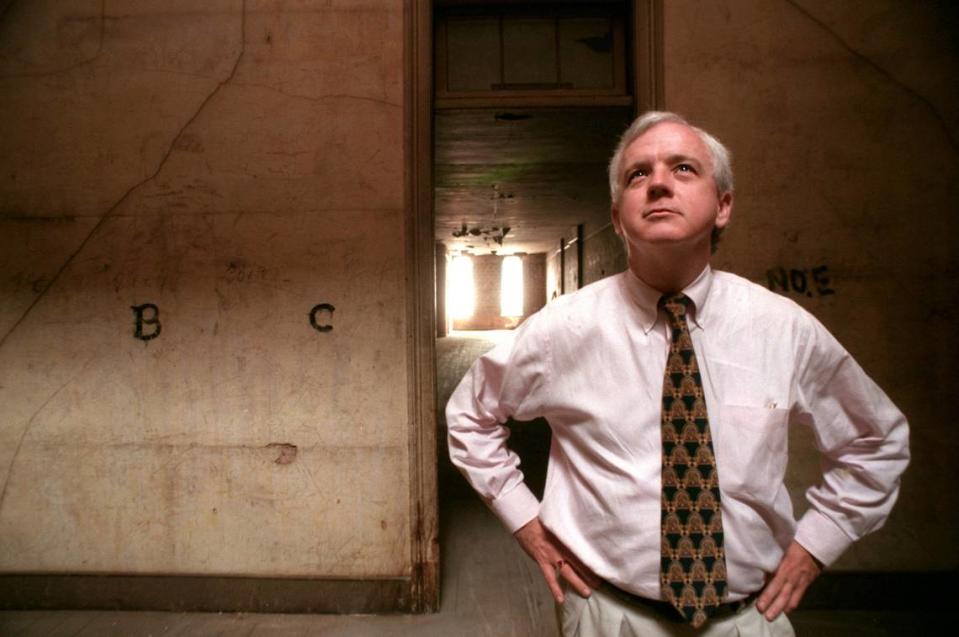

Maggie Gregg believes something like that happens behind the eyes of her longtime boss, Myrick Howard, every time he crosses the threshold of a historic building that Preservation North Carolina has been summoned to try to rescue. Howard sees past the fallen chimneys of the 1800s farmhouses and the collapsed ceilings of the century-old schools and envisions, instead, what the structures used to be and what — with a little love and creative financing — they might become.

“He has such an enthusiasm and an ability to convey that vision,” said Gregg, who has been the Eastern regional director for PNC since 2016. “People naturally get excited about what he’s proposing, because he’s so excited and believes in it so much.”

For 45 years, J. Myrick Howard braved chiggers, mosquitoes, flea infestations, scorched roof rafters, rotted floor joists, recalcitrant land owners and unsympathetic zoning boards for the sake of saving nearly 900 structures that tell the stories of North Carolina. He’s The News & Observer’s 2023 Tar Heel of the Year, an annual honor that recognizes North Carolinians who have made a significant impact in the region and beyond.

Myrick Howard has helped save hundreds of buildings. These are 5 of his favorites

Sticks and stones

Howard was born in 1953 in Durham, the second son of a career machinist for American Tobacco. Growing up, his family lived with his grandmother in the rock-solid home his grandfather had built in a working-class neighborhood using bricks salvaged from an old tobacco warehouse.

After graduating from Durham High as a National Merit Scholar with a four-year scholarship from American Tobacco, Howard went to Brown University for two years before transferring to UNC-Chapel Hill for an undergraduate degree in history.

He moved straight into grad school for double degrees in city planning and law, heading for what he expected to be a career in environmental law.

But along the way, he took a class in historic preservation and, “I got the bug,” he says, which prompted a professional detour that wasn’t as wild a turn as it might first appear. Some of the same statutes apply in both settings.

Meanwhile, from the 1950s through the 1970s, his hometown had undergone the same kind of “urban renewal” that happened across the country with the help of federal Housing and Urban Development and transportation grants. While aimed at updating aging infrastructure and encouraging economic growth, urban renewal nearly always resulted in the destruction of lower-income neighborhoods and business districts, with residents getting displaced and buildings being bulldozed. Often the structures were replaced with highway bypasses, such as the Durham Freeway, or their former lots were simply left empty.

Much of Durham’s African American community of Hayti was razed during that period, along with businesses and institutions that made up the Howard family’s daily life. Down came the school where Howard’s mother had worked as a secretary. Down came the car dealership that had kept his father on the road. The drug stores, the barber shops, the clothing stores and shoe shops, down, down, down, down.

Howard also recalls going with his father as a young boy to watch as one of the mansions of the Duke family — founders of American Tobacco — was demolished. They weren’t there to mourn, Howard says, just to observe as something that had once stood so proud was brought to the ground in someone’s notion of progress.

By the time he heard a UNC professor talk about the need to save the buildings that connect people to the past, Howard intuitively understood that buildings are part of the fabric of a community.

“I think there is something to be said for feeling connected,” Howard says, and buildings draw us together through the people who design, build and own them and all the ways we use them over time.

“As long as the building remains, you can continue to tell the stories,” Howard says. “Once the building is gone, it’s eventually forgotten along with the stories.”

He had one job

After graduating from college, Howard got a full-time job offer with the National Trust for Historic Preservation in Washington, D.C. It would have been an auspicious start had he taken it, but Howard wanted to work in North Carolina. He took a part-time position instead with what had started in 1939 as the North Carolina Society for the Preservation of Antiquities.

Like the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, formed in 1853 to acquire and preserve George and Martha Washington’s Virginia plantation home — launching the nation’s historic preservation movement — the North Carolina group consisted largely of wealthy white women interested in properties connected to other wealthy white people.

The Antiquities Society primarily saved historic North Carolina buildings by turning them into museums or helping local communities do so. One of its most notable accomplishments came in the 1950s, when it reconstructed Tryon Palace in New Bern, using the original blueprints on the actual foundation of the Colonial capitol that was first built in 1770 and burned to the ground in 1798.

In his book, “Buying Time for Heritage,” first published in 2007 and updated and re-released this fall to explain why and how to operate a revolving fund to save historic buildings, Howard describes the Antiquities Society of the 1970s as largely having run its course. Its membership was aging and its board of directors was huge and unwieldy. So it reorganized in 1974 and spun off a separate nonprofit to launch a statewide N.C. version of the revolving fund that Savannah, Georgia, had created to save whole blocks of its 18th- and 19th-century beauties.

The revolving fund, designed to be nimble to move quickly in a changing real estate market, launched in 1976 with a $35,000 grant from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation. Its first director was Jim Gray, a former Winston-Salem newspaper publisher who had led the 1950s campaign to restore the Moravian settlement of Old Salem.

Gray hired Howard in 1978, and a month later went part-time as the development director, making Howard the executive director of what’s now Preservation North Carolina.

Until he retired from the organization this past summer, “It was the only job I ever had,” Howard likes to say.

Not all old buildings can be saved. Myrick Howard recalls 5 in NC lost to history

No more dusty museums

PNC’s purpose was to use its revolving fund to save endangered historic properties, but not by buying them to turn them into museums, which are expensive to operate and seem designed to torture restless children.

Plus, as a wavy-haired Howard in a pin-striped, three-piece suit told Bill Friday in a 1979 interview on UNC TV’s “North Carolina People,” PNC didn’t want to focus just on the fanciest home in a town built for the most successful merchant or magnate.

Save the house where the textile mill superintendent lived, yes. But get the smaller, simpler houses where the mill hands lived, too.

“I think a lot of people have been very disenchanted with what happened during the last 20 years in the name of progress,” Howard said in the 1979 interview, referring to urban renewal and the loss of buildings associated with the Black and white working class. “A lot of things were torn down that people really cared about, and they’re interested now in preserving more than just the one house museum for the town. They’re interested in preserving their hotel or railroad station or a neighborhood.”

As the cost of new building materials rose and the quality of construction declined, Howard believed many people would choose on their own to rehabilitate well-built older homes and commercial structures. So a nice building in decent shape on a main street would naturally attract buyers; it wouldn’t need the help of a statewide revolving fund.

Howard decided early on that where PNC could do the most good was working with the buildings that real estate agents weren’t clamoring to get the keys for, that had sat vacant for years, that people either didn’t notice when they drove past or, if they did, they thought, “Shame that place is left to rot like that.”

As Howard has always described it, “We’re the animal shelter for historic buildings,” specializing in the blind, three-legged, flea-bitten dog stranded in the highway median.

“He has plenty of good years left,” Howard says. “Maybe he just needs a bath.”

Howard, who is gay, felt comfortable in the field of preservation from the start. It was more welcoming than some other professions in the state in the late 1970s, he says, partly because gay men were helping lead the revival of older neighborhoods near downtown Durham and in Raleigh’s Oakwood.

His board of directors also included gay members, Howard recalls, and allies who appreciated his work. Once, when a staff member complained that Howard’s sexuality was somehow a basis for her to make a sexual harassment claim, the board dismissed it.

“There were people who had my back, and I knew it,” he says.

To the occasional surprise of his audiences, Howard reminds preservation groups to consider gay couples when they’re looking for estate donors, in a category called planned giving.

“You’re not asking them because they’re gay,” Howard says, but because they may want to leave a legacy but might not have children to name in a will.

A simple premise

PNC’s goal was this: to acquire endangered historic properties and find purchasers willing and able to rehabilitate them.

PNC often acquires buildings as donations, which it may have to stabilize and secure with roof repairs, a lock or sheets of plywood over the windows to keep thieves from taking what remains of the woodwork. Other times, the organization negotiates an option on a property, with no money down but a set window of time in which to try to sell it.

When it finds a buyer, PNC first buys the property and then resells it to the new owner in the same day, so the organization can place protective covenants on it. Every property that PNC works with transfers with legal covenants that guard its important historical aspects in perpetuity, but still allow for creative reuse.

“We don’t want to get too precious,” Howard says, echoing what he has taught in his city and regional planning class at UNC for 35 years. “If you get too restrictive, you scare people away.”

It sounds simple, but just as restoring these buildings can be full of surprises, so can the process of buying and selling them, which can take years and requires a level of patience the average real estate salesperson can’t fathom or afford.

It often begins, Howard says, with a property owner reaching out to one of PNC’s three field representatives across the state to say they have a house that’s been in the family for generations and they want to hand it off to someone who will take good care of it. Or maybe it’s an old hardware store they bought with plans to renovate it themselves, but it turned out to be more than they could manage.

Occasionally, PNC learns of a building worth rescuing and approaches the property owners to see if they’re willing to sell.

Then comes the research to determine why the building is worth saving and if, in fact, it can be saved. Not every building can.

PNC’s first choice is always to keep historic structures in their original context, like dinosaur bones in an archaeological dig. Will the owner sell the land the house is sitting on? Or must the building be moved? Would it even survive being moved?

If PNC gets involved with a building, it commits for the long haul: marketing it, showing it, helping potential buyers see possible reuses and suggesting ways to fund the purchase and the renovations. Once it’s sold, the group often guides owners who want to do some of the work themselves or connects them with specialized craftspeople.

Then, if the property changes hands again, PNC makes sure new buyers know they must honor the protective covenants.

Though he’s normally as friendly and approachable as a well-appointed front porch, Howard knows the law and isn’t afraid to use it.

A would-be developer once told Howard he had plans for a property that PNC had protected and said, “I don’t care about your covenants.”

OK, Howard said, “But how do you feel about your real estate license?”

Sometimes, the best way for PNC to save a building has been for the organization to buy it, renovate it and move its offices there. It’s done that five times, including the old Briggs Hardware Building on Fayetteville Street in downtown Raleigh and most recently with the Rev. Plummer T. Hall House and the Graves-Fields House in Raleigh’s Oberlin Village, which PNC joined and occupies now.

Besides serving as a beautiful headquarters, the two buildings give PNC a chance to tell the history of important African American families from Raleigh’s past.

Before renovations, many potential buyers can only see what’s in front of them, Howard says. The wrecked Titanic on the ocean floor. The weather-beaten house with no electricity or running water on the outskirts of a rural North Carolina town.

“You have to show them what’s possible,” he says.

A bottomless toolkit

Howard loves old buildings so much he has renovated three of his own in what’s now called the Forest Park neighborhood of Raleigh, though Howard notes it’s legally still Cameron Park. He could lead workshops just on how to convert a duplex back to a single-family dwelling or vice versa, or how to connect with your neighbors while tending flowers in the front yard.

But the tools he’s most comfortable with are the legal and financial ones he has deployed to help protect those 900 historic structures across the state. They’re real estate tools, because despite the emotion that old buildings spark in him and others, Howard believes it’s crucial to separate those feelings from what is essentially a property deal.

“Historic preservation is real estate, and you use real estate tools to get where you need to be with the buildings. You have to get emotion out of the picture,” Howard says.

Historic buildings can generate negative emotions, too.

In November, Howard held a PNC-benefit book signing for “Buying Time” at the Bellamy Mansion in Wilmington, the only property PNC acquired, rehabbed and operates as a house museum.

The 10,000-square-foot home was built for physician and merchant Dr. John D. Bellamy using the skilled labor of enslaved people and free Black artisans in the Wilmington area between 1859 and 1861. The property includes an extremely rare original two-story urban slave dwelling, where today’s guests learn of the hardships and also the ingenuity and resilience of the city’s early Black residents.

But when PNC was given the property in the 1990s after the house had been firebombed and nearly abandoned, neither Black nor white North Carolinians were necessarily enthusiastic about preserving and displaying an extravagant antebellum home made possible by the exploitation of enslaved people.

Dr. Valerie Ann Johnson, dean of Arts, Sciences and Humanities and a professor of sociology at Shaw University, chairs the board of directors of PNC. She says Howard was able to bring all kinds of voices into conversations around the Bellamy Mansion to guide decisions about how to preserve and interpret the property. He is so naturally and aggressively inclusive, she says, he makes people believe they belong.

“He sees things not just in these buildings, but in people,” Johnson says. “I had not really thought of myself as someone who could be a board member, which he did, and that’s great. But then to be asked to be chair of the board, and to come lecture in his classes, that’s the kind of support and mentorship he brings.

“It’s not just saying things, it’s actually opening up opportunity.”

The National Trust cited Howard’s work as a mentor, thought leader and practitioner when it awarded its highest honor to him earlier this year, the Louise du Pont Crowninshield Award. Named for one of the National Trust’s founding trustees, it denotes superlative work in preserving and interpreting America’s historic, architectural or maritime heritage.

As he did hundreds and hundreds of times while leading PNC and will continue to do now that he’s retired, Howard set up a projector with a slideshow to highlight the work PNC has done through its revolving fund and encourage any of the two dozen or so people in attendance to invest in a historic property if they are so inclined.

In his talk, in an upstairs parlor of a house that was brought back from a catastrophic fire and decades of neglect, Howard repeatedly toggled back to a slide featuring a grid of boxes, each naming a tool of the trade.

Some of the most important ones are income tax credits for the rehabilitation of historic properties, which PNC helped get written into state law in the 1990s. The credits have been used to save buildings across the state and adapt them to modern uses, meaning PNC can be credited with indirectly helping preserve thousands more structures than the 900 it has placed covenants on.

Some of the most remarkable ones that have made PNC a national model are the former public schools converted to affordable housing, including units for the elderly; and the former mills and mill villages that continue to be transformed into modern housing and commercial space.

As always, in his slideshow, the before-and-after photos were the favorites, drawing gasps from people who could suddenly see, as Howard always has, what’s possible.

2023 Tar Heel of the Year: J. Myrick Howard

Born: Durham, April 22, 1953

Education: National Merit Scholar, Durham High School; attended Brown University, transferred to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for a bachelor of arts degree in American history; received his master’s in regional planning and a law degree, both from UNC.

Family: Partner, Rob Southern. Brother and sister-in-law, Charles and Cindy Howard of Waxhaw; two nieces.

Career: Spent his entire professional life as head of Preservation North Carolina, hired in 1978 and retired in 2023. During his tenure, the nonprofit expanded its staff, budget and scope, protecting nearly 900 buildings across 85 counties and becoming a national model for using a revolving fund to save the buildings that connect people.

Helped craft the law creating state tax credits for historic preservation and wrote the book on how to do this work, publishing “Buying Time for Heritage” in 2007. An updated edition was released this year by UNC Press.

Plan for retirement: Supporting plans to preserve what remains of the original three-story Tuscan Revival center building at what was Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh. When built in 1856, using the labor of enslaved and free Black people, it was the largest building in the state and was designed to work with its site to provide a healing environment.