Residents in other states are protected from all summer utility shutoffs. Should RI do the same?

PROVIDENCE – Torrell Mola realized her electricity had been shut off when she tried to turn on the lights in her apartment. She came home from a trip, flipped the switch in the living room and nothing happened.

Rhode Island Energy had mailed notices warning that her electric and gas services would be terminated unless she started paying the thousands of dollars she owed the company, but they arrived while she was visiting her niece in California with her teenage daughter. They found the papers hanging on the front door to their apartment July 20.

Mola, a single mother of two with multiple sclerosis, had been working two days a week at a daycare center, but she lost her job last spring after a water pipe burst in the center and shut it down for repairs. Her only source of income is a monthly Social Security check for $1,300.

“It was either pay rent or pay my utilities,” Mola said.

If it had been winter, Mola's utilities wouldn't have been shut off because of seasonal protections in place for families with serious illnesses, the unemployed, the elderly and other at-risk Rhode Islanders. State law forbids utility companies from cutting off gas or electric service between Nov. 1 and April 15 because of the need to protect the most vulnerable residents from the cold weather. State regulators often extend the winter moratorium to May.

But in summer, the protection is much weaker. There is no blanket moratorium.

The only times utilities are prohibited from shutting off customers in the warmer months are when the National Weather Service issues a heat advisory for Rhode Island, which occurs when the heat index, a measure of temperature and humidity, is forecast to reach 95 degrees for two or more consecutive days or 100 degrees for any period of time on a single day.

Those windows of time don't protect people from having their power cut off a day, two days or a week before a heatwave – when there might be still a dangerous heat day in the 90s but not yet at the moratorium mark.

Climate change is making summers longer and hotter, driving the need for more air conditioning. The impact can be even greater in urban neighborhoods with lots of asphalt and few trees, so-called heat islands where temperatures can be 10 to 15 degrees higher than in leafy suburbs.

Rhode Islanders are being hit even harder this year as electric rates are higher than normal, meaning that people like Mola are facing bigger monthly bills that are pushing them even further behind on what they owe.

Rhode Island's shutoff policies are better than many. While 41 states have winter protections, only 20 have them for the summer – and in many cases the laws around heat are weak or ambiguous, according to the Energy Justice Lab. Rhode Island is the only state in New England with a summer policy, but its temperature-based approach lags those in states such as Delaware and Missouri that prohibit disconnections during broad time periods.

Advocates say conditions will only grow worse as temperatures continue to climb. They are calling for stronger protections for ratepayers as climate change makes air conditioning in the summer as essential as heating service in the winter. At the heart of the demands in Rhode Island is implementation of a program they have been pushing for decades that would allow poor people to pay only what they can afford for gas and electric services.

“People associate utility vulnerability with the wintertime,” said Camilo Viveiros, executive director of the George Wiley Center, an organization that advocates for the rights of marginalized Rhode Islanders. “But conditions are making it an issue year-round.”

Energy bills are likely to keep rising

Electric bills spiked across New England last year. The region’s power grid is largely dependent on natural gas as a generating fuel, so when the war in Ukraine and post-pandemic inflation drove up wholesale prices for gas to astronomical levels, the rates paid by consumers followed.

In Rhode Island, electric rates reached their highest point on record last winter. Rates typically come down when the weather warms and demand for gas for home heating ebbs, but they remained substantially higher than usual this past summer. Increasing the pressure on Rhode Islanders, they’re climbing back this winter to last year’s levels.

The high electric rates are coming at a time when summers are growing longer and hotter in Rhode Island, where temperatures have risen almost 4 degrees since 1900, making it among the fastest-warming states in the nation.

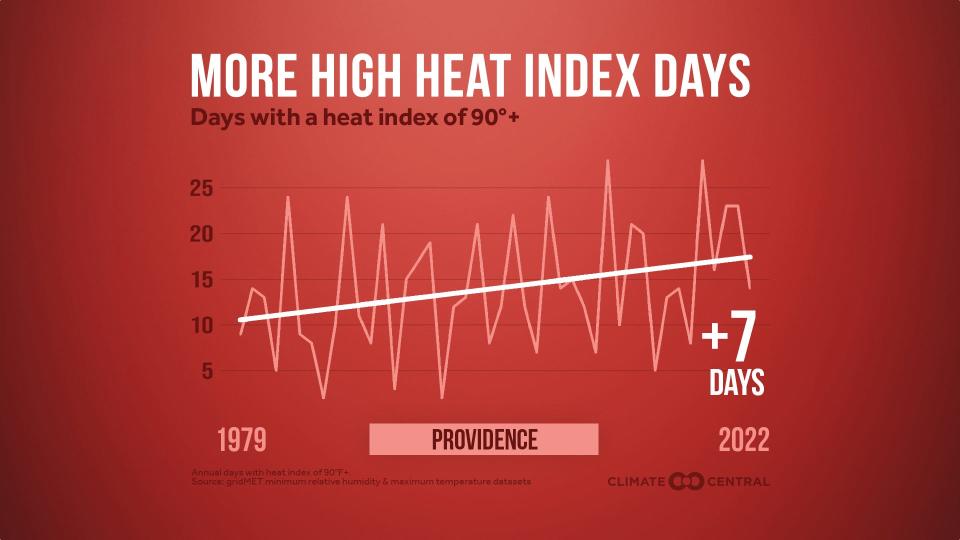

Historically, Rhode Island experienced about nine days each year when the heat index, or “feels-like” temperature, was above 90 degrees, conditions that can be physically hazardous, especially for the elderly, people with health conditions and other high-risk individuals. That number is expected to quadruple by midcentury and nearly double again by the end of the century, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists.

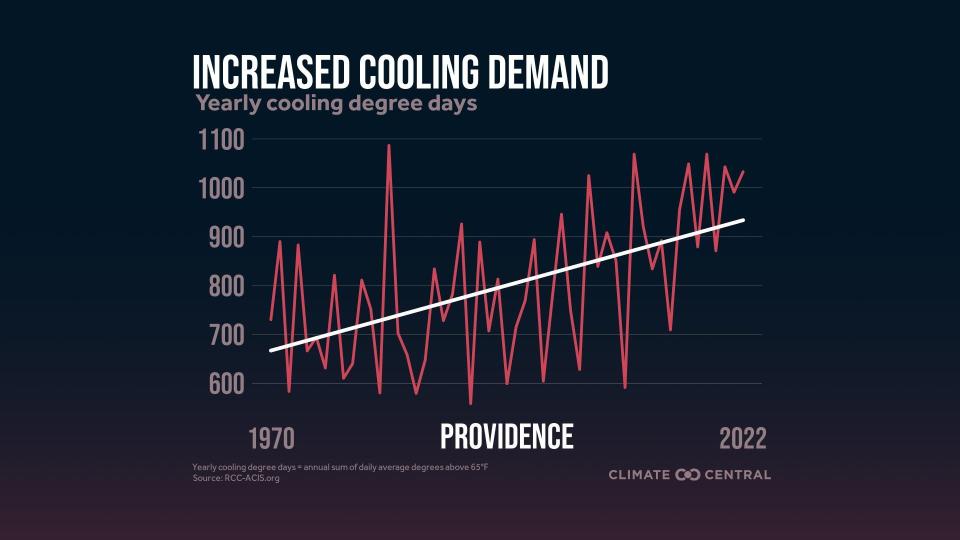

Higher temperatures are fueling a need for more air conditioning, as demonstrated by an increase in cooling degree days, units that measure the difference between the outdoor temperature and an indoor standard of 65 degrees. Cooling degree days quantify air conditioning demand. A day, for example, with an outdoor temperature of 80 degrees would have 15 cooling degree days.

From 1949 to 2009, there were never more than 600 cooling degree days per year on average for New England. From 2010 to 2022, there were five years that topped that number, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Between 1998 and 2022, the average for the prior 10-year period jumped from 417 days a year to 561 for the region – outpacing the increase for the nation as a whole.

For Rhode Island specifically, the number has shot up by more than 30% since 1970, according to Climate Central. It is expected to continue to rise as the state warms more.

This summer was milder in the Northeast compared to recent years, but the average temperature in July was still higher than the climate normal as were the number of cooling degree days between June and August, according to the Northeast Regional Climate Center at Cornell University.

Because New England relies so heavily on natural gas to generate power and there are constraints on supply, electric rates in Rhode Island and neighboring states have long been among the highest in the nation. Increased demand for air conditioning is only adding to an energy burden on low-income households that in New England is the highest in the nation compared to other regions as a percentage of how much is spent on bills, according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. In Rhode Island, low-income households spend an average of 8% of their income on energy compared to 3% for median-income households.

After the winter moratorium on shutoffs in Rhode Island lifts, Rhode Island Energy starts sending tens of thousands of termination notices to customers in arrears. Many customers make minimum payments or agree to payment plans to stave off termination, so the number of shutoffs in past years has generally numbered in the low thousands or high hundreds each month.

More: Pay what you can? Proposal could help low-income Rhode Islanders with gas, electric bills

More recently, for a number of reasons, shutoffs have been fewer. State regulators suspended all terminations through much of 2020 during the height of the COVID pandemic. Additionally, when Pennsylvania-based PPL Electric Utilities took over as the major utility provider in the state last year and formed Rhode Island Energy, it agreed to forgive $43.5 million owed by low-income customers, which resulted in some 24,000 people having their debts reduced. Lastly, a stay on terminations for certain classes of customers was enacted after a lawsuit was filed in 2015 by the Rhode Island Center for Justice that sought clarification on language in the shutoff regulations.

The pandemic is now over, the arrearage forgiveness was a one-time concession, and the court case was resolved in August, meaning the stay was lifted. As a result, state utilities regulators expect shutoffs to rise again.

Rhode Island Energy says customers have options to keep their utilities on and encourages people in trouble to reach out for assistance, but the company is forecasting a similar trend as regulators.

“We do expect the number of shutoffs to continue to climb as time goes on, but our hope is that we won’t ever see such high rates that existed pre-COVID,” spokesman Ted Kresse said.

Temperatures climbed this summer, but the power was off. What to do?

Mola did her best to make do after losing her utilities.

She got used to living without lights. She opened her curtains during the daytime and borrowed battery-powered lanterns from her mother’s neighbor to use at night.

Mola’s 13-year-old daughter had a harder time being without power and moved in with Mola’s sister. Mola’s 19-year-old son moved back in to help out.

The shutoff came during the hottest stretch over the summer in Rhode Island. As the heat index climbed into the upper 90s, Mola started to suffer. She opened the windows to get fresh air into her apartment and took cold showers to cool off. She ran an extension cord into her downstairs neighbor’s apartment just so she could run a fan.

Mola was diagnosed in 2008 with multiple sclerosis, a chronic disease of the central nervous system that can cause pain, fatigue and cognitive impairment. Even a slight elevation in body temperature can lead to a worsening of symptoms, according to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Mola says the heat saps her energy. During the summer, she tries to avoid going outside until the sun sets and the temperature drops. Without electricity to power her window air conditioner units, she was forced to rest more than usual.

"When I felt my temperature rising, I had to lay down and go to sleep,” Mola said.

Before her disease worsened, Mola worked full-time as a medical secretary at Rhode Island Hospital. She left in 2011, because of forgetfulness that can be a symptom of the disease, and went on permanent disability.

In the years afterward, her debts to the utility mounted, in part, she says, because her family lived in a single-family home that had older electric-resistance heating, which is among the most expensive methods of home heating. She says she now owes $13,000 in electric bills and $7,000 for gas.

It’s unclear how she was able to run up such substantial debts without having her services shut off for so long. She would have been protected in the winter when the shutoff moratorium is in place because she’d submitted documentation with a doctor’s signature and was classified as seriously ill.

That status would have also temporarily offered her year-round protection, according to regulators, because cases like hers were subject to the stay put in place during the Center for Justice’s lawsuit. In any case, to retain her seriously ill status, Mola would have had to reapply. She’s unsure if she did so.

In April 2022, after she and her daughter moved into their current apartment in a Providence triple-decker, Mola received notice that her services would be disconnected for failing to pay her bills. She wasn’t sure what had gone wrong. As she tried to figure out a solution, her utilities were cut off.

She reached out to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, which paid the utility $1,400 as a down payment on her debt, and her gas and electric connections were restored.

At the same time, she tried to get re-certified as seriously ill, filing a new application for protected status. But she’d unknowingly forgotten to get a doctor’s signature and the application was rejected.

She was protected from being shut off again because of the winter moratorium, but after it came to an end, the new notice arrived. It was only after she came home to an apartment without power or gas that she says she realized her application hadn’t been approved.

Mola felt overwhelmed and frustrated.

“At times, I thought I wanted to give up, but I can’t,” she said. “I’m all my kids have and I have to keep it together for them.”

She turned to the George Wiley Center for help.

The role of a center focused on basic rights in RI

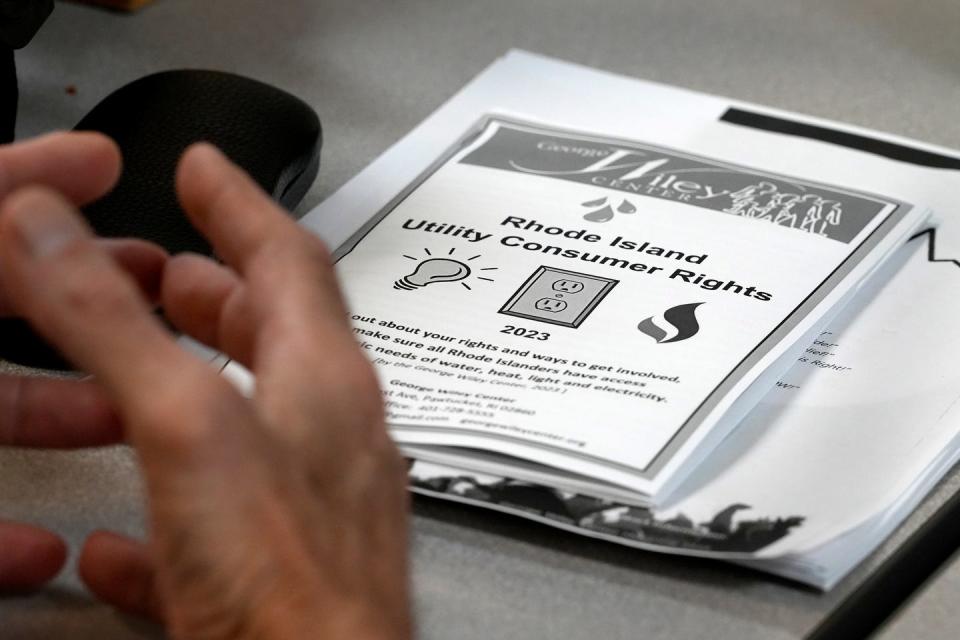

Inside a narrow storefront in downtown Pawtucket, a dozen people gathered around a conference table one Wednesday night to talk about ways to help prevent shutoffs.

The Wiley Center’s office is unassuming and easy to miss, tucked between a martial-arts school and a store selling herbal supplements, but it’s been at the head of efforts in Rhode Island for more than four decades to treat access to electricity, heat and water as rights, not privileges.

Anti-poverty activist Henry Shelton founded the center in 1981 and named it after Wiley, a Rhode Island native who rose to national prominence as a champion of the rights of welfare recipients before his drowning death in 1973 at the age of 42. Shelton died in 2016, and Viveiros now leads the center’s work.

There have been victories in reducing the number of summer shutoffs. In 2007, Rhode Island became one of the first states to enact a moratorium on terminations when the temperature spikes – specifically, whenever the National Weather Service issues a heat advisory. In the early years of the rule, per weather service policy, that would only occur when the heat index was forecast to reach 100 degrees for at least two consecutive hours.

But in 2017 researchers in Rhode Island, Maine and New Hampshire found that that people with pre-existing conditions, such as asthma and heart disease, the elderly, people who work outside and people from lower-income communities fared much worse when the heat index reached 95 degrees.

As a result of the study’s findings, the weather service lowered the threshold to its current level. The Wiley Center, however, maintains that the moratorium is still too weak – Viveiros says he’s unsure when it’s actually gone into effect – and has been working to try to strengthen it. Options include further lowering the heat index threshold that triggers a moratorium, or using a calendar-based approach that’s similar to what happens in winter.

The Energy Justice Lab, which researches utility policies across the nation, says the nation is facing a national crisis with utility disconnections. Its directors, Sanya Carley and David Konisky, counted 3 million shutoffs across the nation last year. They found that half of all households that have been disconnected face the same problem again within the same year.

Carley, professor of energy policy at the University of Pennsylvania, and Konisky, a professor at the O'Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, say that the problem is particularly acute in the summer when protections are weakest and that rising temperatures will only exacerbate the situation for many Americans.

"We believe that the crisis will only get worse as the impacts of climate change become more widespread and more severe," they wrote in The Conversation. "In our view, it is time government agencies and utilities start treating household energy security as a national priority."

Broader problems persist beneath climate vulnerability

Viveiros and others at the Wiley Center consider any changes to the summer moratorium in Rhode Island as Band-Aid solutions to a much larger problem with energy affordability in the state.

Although Rhode Island Energy does offer discounts to low-income customers of up to 30% on their bills, advocates for reform believe more needs to be done. They say the most effective answer is what’s known as a Percentage Income Payment Plan, a program that would allow low-income Rhode Islanders to pay only what they can afford for power and heat.

PIPP was piloted in Warwick in 1986, but came to an end a few years later after funding dried up. Other states have created similar programs, but efforts led by the Wiley Center to resuscitate it in Rhode Island have proven unsuccessful. The tide appeared to have turned in this year's legislative session after PPL Electric Utilities, which has a PIPP in Pennsylvania, signaled that was open to creating such a program in Rhode Island. It came after years of opposition from National Grid, the former owner of the Rhode Island business.

Under the proposed legislation, low-income households would pay no more than 3% of their income on their electric bills and 3% on their gas bills. If they use electricity for heating too, then the cap would be 6% of their income on their electric bills. The program would be paid for by all other utility customers through a surcharge for low-income energy programs that’s already on their bills.

Despite positive committee hearings, the legislation didn’t advance in the House or Senate.

Viveiros has been organizing meetings all summer to educate ratepayers about utility laws. On this night, he helped walk one woman who received a shutoff notification in the mail through options that included making a minimum payment and asking for an extension. The date of termination listed in the notice had passed, but Rhode Island Energy hadn’t yet disconnected her service.

“It’s stressful living with the fear of being shut off,” Viveiros said.

He was joined around the table by Adam Schuck and Edward De La Cruz, who met in the pre-med program at the University of Rhode Island and have been volunteering to assist people facing termination. The pair worked together to design a computer application that makes it easier for people to fill out the forms to qualify for protected status.

Daisy Benitez, an organizer with the center, was also there. She started volunteering at the Wiley Center in high school, its work resonating with her because, she says, her family, which immigrated from Mexico, has also dealt with poverty and food insecurity. She said the center gets eight to 10 visits a day from people facing utility shutoffs and that staff field phone calls throughout the day from others in the same situation.

She worries that people who have their services shut off when the weather is hot could end up in the hospital. But her opposition is broader. She doesn’t believe utilities should shut off vulnerable people's service at any time of year.

“It’s just punishing people for being poor,” she said.

Is there a role for the medical community?

After Mola called the Wiley Center, she went to see Benitez in the Pawtucket office.

Benitez directed her to the app developed by Schuck and De La Cruz so she could fill out the forms to be recertified as seriously ill. Schuck sent her information to Dr. Rahul Vanjani, the medical director at Amos House, who reviewed her case and signed the necessary documentation.

Dr. Vanjani, who also teaches at Brown University's medical school, says that shutoffs are an issue of public health and that physicians can play a vital role in preventing them.

"Incorporating preventive measures against utility shutoffs into medical practice not only reflects a commitment to patient welfare but also aligns with the broader public health goal of minimizing heat-related health challenges," he said. "As temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, physicians' involvement in preserving essential utilities takes on even greater significance, safeguarding lives and promoting a healthier, more resilient community."

Mola's gas was reconnected on Aug. 1 and her electricity followed two days later. She doesn’t think she would have been able to resolve the situation as quickly if the Wiley Center hadn’t helped her.

She said Rhode Island Energy informed her that she won’t have to apply for recertification for her seriously-ill status until 2025. She’s still trying to work out a payment plan with the company to address her debts.

She said she’s sharing her story because she wants to help other people facing similar circumstances. She said she wishes she’d known about the Wiley Center when she started racking up unpaid utility bills. But she also questions why the system is so complicated that outside help is necessary to navigate it.

After getting her power back on, she said the first thing she did was turn on her air fryer.

“I ran to the supermarket,” she laughed. “I just wanted a bagel.”

The Providence Journal is investigating the effects of a rapidly heating planet on people who live in our city. Follow along with "City on Fire" as we report the struggle with summer temperatures. This is part of the USA TODAY project Perilous Course. Contact journalist Alex Kuffner to be included in a story if you have been affected by heat: expense of air conditioning or lack of it, health risks, less access to green space, concern about pets and animals in summer conditions, worry about an older loved one, etc.

*Background: PIPP was piloted in Warwick in 1986, but came to an end a few years later after funding dried up. Other states have created similar programs, but efforts led by the Wiley Center to resuscitate it in Rhode Island have proven unsuccessful. The tide appeared to have turned this past legislative session after PPL, which has a PIPP in Pennsylvania, signaled that was open to creating such a program in Rhode Island. It came after years of opposition from National Grid, the former owner of the Rhode Island business.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Summer utility shutoffs leave vulnerable RIers without A/C in the heat