Resilience amid violence: Author digs into El Salvador's and his family's past

The drawing that the child migrant showed the journalist Roberto Lovato featured turquoise clouds, stick people and a big white moon.

“Here is how I hope we can live here,” said David, a 6-year-old in detention with his mother in Karnes City, Texas, in 2015. Then he showed Lovato a drawing on his hand of a skull with sharp teeth, saying that it represented what it was like back home in El Salvador. His uncle, David explained, had been shot by a gang through his teeth.

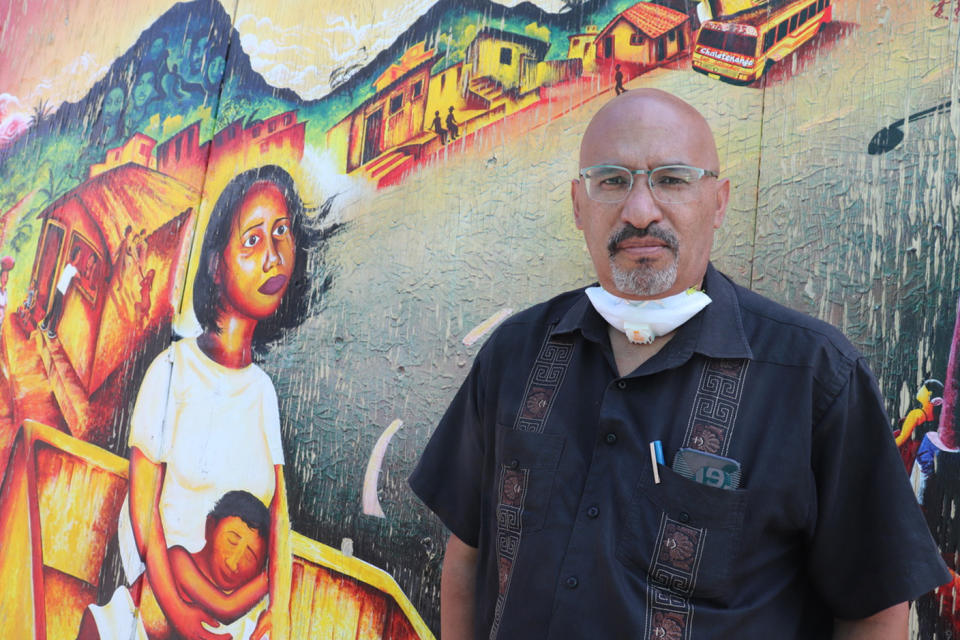

Lovato, who had been visiting the detention center for a possible story on a migrant protest, came away transformed by his encounter with the young detainee. It set Lovato on a journey to explore his family history and his Salvadoran heritage. Now Lovato reflects on his life so far in his new book, “Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and Revolution in the Americas.”

“I wanted to tell the stories I know,” Lovato said. “Seeing that kid in Karnes reminded me of my responsibility to do that, and help people move past simplistic, inaccurate narratives about Central America.”

El Salvador and the United States are bound together by history, Lovato said. “Where most see the refugee crisis as “new,” I see the longue durée (long duration) of history and memory,” he writes. “Where many see the story beginning at the border, I see … violence, migration, and forgetting that extends far beyond and below the U.S.-Mexico border. Where others see mine as a Central American story, I see it as a story about the United States.”

Born in 1963 and raised in the San Francisco Bay area, Lovato is an acclaimed journalist whose work has appeared in The Boston Globe, The Nation and The Guardian. As an activist, he co-founded Presente.org (which helped oust Lou Dobbs from CNN in 2009 over his anti-immigration stance and allegations of bigotry toward Latinos) and “#DignidadLiteraria,” which advocates for more representation of Latinos in publishing.

Publishers Weekly called “Unforgetting” an “intimate gripping portrait of El Salvador’s agony,” while The New York Times praised it as a “groundbreaking memoir.”

Lovato’s complicated life included stints as a gang member as well as a born-again Christian. He later briefly joined up with a guerrilla movement fighting in El Salvador. He’s witnessed the exhumation of mass graves — and learned how his own family's secrets intertwined with El Salvador’s history of violence and trauma.

“One of the arcs in my book is me and my dad,” Lovato said, “while another is me and my patria, my fatherland. All of us born here have these issues being 'ni de aquí, ni de allá' — neither from here nor from there.”

U.S. policies, current violence

In “Unforgetting,” Lovato details how American policies have for decades directly affected El Salvador. In the 1980s, the U.S. government fueled a civil war in the country that lasted for 12 years and killed over 75,000 people. In the 1990s, the U.S. deported gang members to El Salvador, where they regrouped and became stronger than ever. The resulting violence has driven thousands of Salvadorans to flee to the U.S.

According to the Pew Research Center, in 2017 there were 2.3 million Salvadorans in the U.S., making them the third-largest population (tied with Cubans) of Hispanic origin in the country.

In the U.S., Salvadorans and Americans of Salvadoran descent have been hit hard by the coronavirus outbreak. Salvadorans are concentrated in California, Texas and New York, which have all been hot spots for Covid-19.

On Sept. 14, a federal appeals court in California ruled that the Trump administration can end Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a program that gives temporary immigration status to people from certain countries where conditions are unsafe for their return. Trump decided to end the program, and its potential wind down has broad implications for Salvadorans, who at 263,000 are the largest group of TPS holders.

“I am shocked that this decision would come under the pandemic conditions,” said Xochitl Sanchez, an organizer with the Central American Resource Center (Carecen), an advocacy and legal services group for Central Americans in Los Angeles. “It deeply saddens us, but our legal team is going to appeal.”

The TPS announcement has left many Salvadorans feeling scared, Sanchez said. “People were hearing that the program was terminated, and that Trump would be being deporting everyone.” But there are still legal challenges ahead and the possibility of congressional action, Sanchez said, so Carecen is ramping up its outreach efforts to educate their clients.

American, Mexican and Salvadoran policies have, in part, contributed to a drop in illegal migration from El Salvador, said Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, a policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute. In fiscal year 2019, immigration officials reported about 90,000 apprehensions of Salvadorans at the southern border, Ruiz Soto noted; for fiscal year 2020 (which ends in September), there have been roughly 14,000 apprehensions. “We are seeing a drop in the number of unaccompanied children and family units from El Salvador,” he said, “and the asylum process at the U.S./Mexico border has been basically shut down.”

One consequence of the Covic-19 outbreak is the drop in remittances sent by Salvadorans abroad to their home country. One-fifth of El Salvador’s GDP comes from remittances, Ruiz Soto pointed out. ”Remittances are a key component of the Salvadoran economy, and their drop-off, which we’ve seen, will likely worsen conditions in the country if the trend continues,” he said.

"Our future depends on remembering ... "

The violence and instability that Roberto Lovato writes about in “Unforgetting” is still present in El Salvador.

José Manuel Vivanco of Human Rights Watch said that Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s “actions have shown absolute contempt for judicial decisions, attacks on press freedom, and intolerance to criticism and dissent.” In an email, Vivanco wrote that Bukele had used the pandemic to “order a repressive nationwide lockdown” and that he had demonstrated “despotic behavior” and “polarizing and authoritarian tendencies.”

Despite the persistence of such conditions in El Salvador, Lovato is committed to unearthing the stories of his family’s homeland. “I realized that learning both Salvadoran history and the history of my family was essential to understanding my story,” he writes. “Our future depends on remembering that we are a fierce, resilient people forged in a crucible of poverty and staggering violence.”

“We need epic stories for the epic times we live in,” Lovato said. “We need to urgently commit not only to the future, but also to the past — to the truths that the past offers us, that will allow us to navigate these challenging times.”

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.