Retro: In Baltimore and Washington, civil rights protests during the summer of 1963 still reverberate

In the summer of 1963, civil rights advocates made significant strides in breaking segregated barriers here in Maryland and nationally.

Black Baltimoreans, interfaith leaders and allies were organizing and preparing for demonstrations, such as the March on Washington — which included nearly 6,000 people from Baltimore — and the desegregation of Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Woodlawn.

Today, that amusement park is Gwynn Oak Park, 64 acres of grassy land and picnic tables in Baltimore County. But in the summer of 1963, demonstrators from different religions and racial backgrounds drew national attention to the area by protesting against the private park’s segregation policy, which allowed only white visitors.

Around 3 p.m. on the Fourth of July that year, demonstrators attempted to enter the park from various directions. Some successfully entered through the front and back entrances. As demonstrators peacefully protested, they were met with racist reactions from parkgoers.

“Negroes tried to enter the park but were repulsed and arrested as white hecklers howled and cursed them,” The Sun wrote at the time.

The Black press in Baltimore not only reported on the protest, but also participated in it.

Jimmy Williams, former assistant managing editor of the African-American, was arrested during the demonstration.

“There comes a time in life when one can no longer sit on the sidelines while others fight his battles,” Williams wrote in the Afro in 1963. “For a number of us that time came on Sunday afternoon under a warm and almost cloudless sky and the dark glances and darker words of a mob, we went to jail for entering Gwynn Oak Park.”

White parkgoers hurled slurs and physical objects at the demonstrators. Charles Mason, who was 25 at the time, told The Sun he was hit in the head by a rock.

“They ought to shoot those white trash,” an unknown man in the park told The Sun about white demonstrators.

Religious leaders such as Eugene Carson Blake, the vice chairman of the National Council of Churches, Rabbi Morris Lieberman of the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation, the Rev. Joseph Connolly of the Catholic Interracial Council, Edward A. Chance, a chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality, and other ministers were among the demonstrators.

“Our business is to be where there is action — it is not for us to hide,” said Bishop Daniel Corrigan, director of the Home Department of the National Council of the Protestant Episcopal Church, who was escorted out of the park and into a police wagon alongside other religious figures, according to The Sun.

Police wagons and school buses were used to haul protesters away from the park after their arrest. Nearly 300 of them were arrested for trespassing and disorderly conduct, according to The Sun.

The protest led to the integration of the park. Then-Baltimore County Executive Spiro T. Agnew negotiated the end of the park’s segregation policies with the private owner Aug. 28. Later that day, a Black family entered the park, officially integrating it.

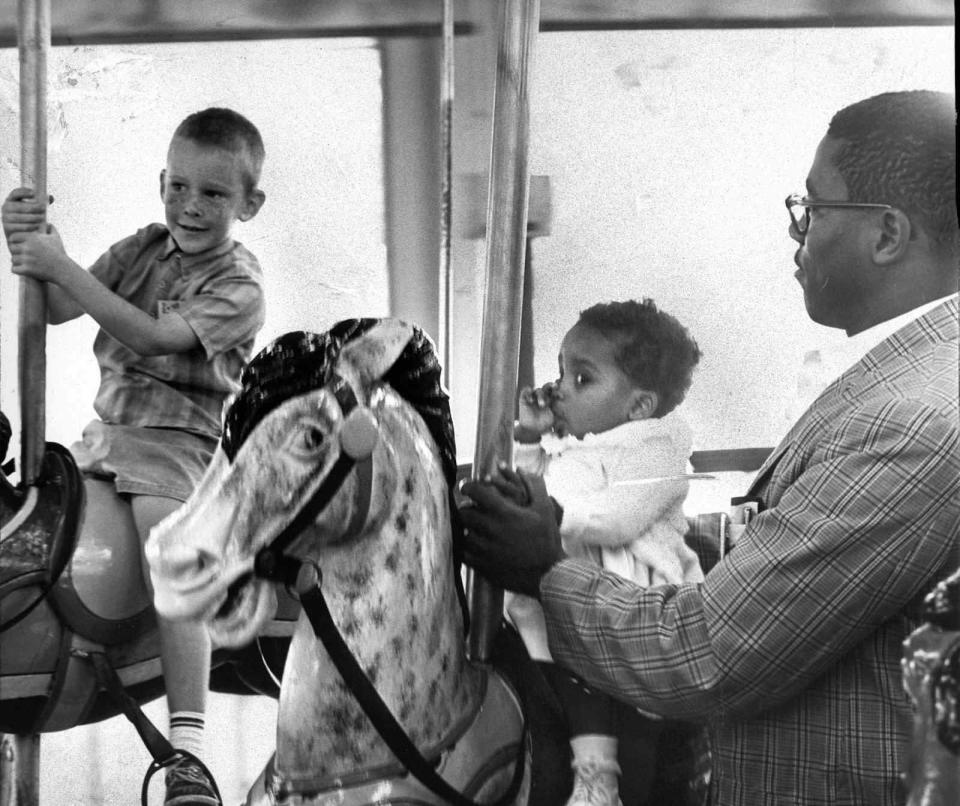

The Langleys, a family from Philadelphia that had moved to Baltimore just four years prior, brought along their 11-month-old daughter, Sharon Langley, who became the first Black child to freely ride the park’s merry-go-round.

While on the ride, a white woman asked Sharon’s father, Charles C. Langley Jr., to watch her daughter as Mr. Langley rode with Sharon, The Sun reported.

“Those are the kind of things that make me feel we’ll be accepted,” he told The Sun in 1963.

The Sun reported the scene as “quiet” and added that it “contrasted” with the protest from July 4 weeks earlier.

Nearly 50 years later, Sharon Langley, then a resident of Los Angeles, returned to Baltimore for the 50th anniversary of that moment in 2013.

“So many ordinary people were part of civil rights,” she said. “I’m glad my family felt this was an important thing to do. Every person has a part to play. Every person can do something in her community to move her community forward.”

On the same day Gwynn Oak Park was integrated, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington, also known as the March for Jobs and Freedom, which drew over a quarter million people.

Protesters told The Sun the only “unsympathetic note” they saw on the way to the march was a car with a sign reading “National Advancement of white people.”

With the bloody road of the late 1960s riots ahead, thousands of Black and white Baltimoreans from different religions demonstrated against segregation back at home. Nearly 6,000 people from Baltimore traveled by bus and cars to protest segregation, with religious leaders and clergy at the forefront.

“Some places we go, we aren’t recognized and can’t eat,” William Meyers, an unemployed cook, told The Sun in August 1963. He said he was sometimes told a job wasn’t open to Black people.

The summer of 1963 wasn’t as violent as previous summers in Baltimore.

Juanita Jackson Mitchell, the former president of Maryland’s NAACP Baltimore City branch and civil rights advocate, spoke about the harshness of Baltimore in the 1920s.

Mitchell was among those who pushed for Maryland to be the first Southern state to integrate schools after the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education. Like many Black people in Maryland, Mitchell attended college outside the state due to segregation laws of the time. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech resonated with the then-70-year-old’s experience.

“This was a mean city,” she told The Sun in 1963 in reference to Baltimore in the 1920s.