Rev. Charles Adams was more than a pastor. He changed Detroit | Opinion

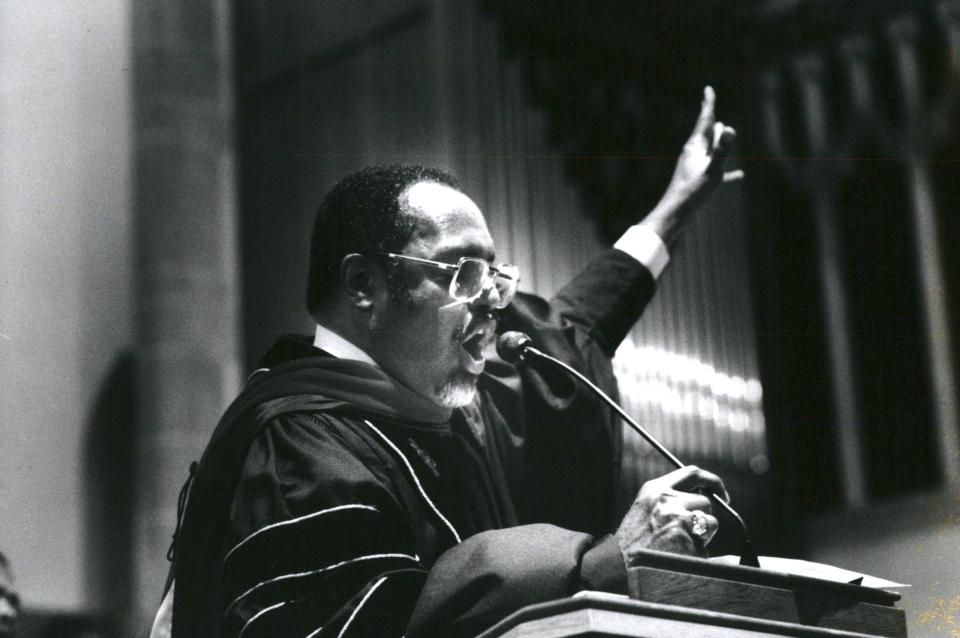

When the Rev. Charles Adams gave his iconic “thank ya” speech at Rosa Parks’ funeral in 2005, he introduced the world to the theological genius we in Detroit called our own.

It was a prayer that turned into a mini-sermon about Parks’ contributions to society for Black America.

“She sat there so we could sit in higher seats,” Adams said three minutes into his prayer. “And because she sat where she sat, we are now sitting in the halls of Congress, sitting as presidents and CEOs as heads of global corporations, as heads of Ivy League schools, pastors of megachurches, secretary of states and sitting at the table where cosmic decisions are made. We thank you for where she sat.”

I was there that day, covering Parks’ funeral. The crowd went wild. Many at Greater Grace Temple leapt to their feet. Smiling, the Rev. Jesse Jackson stood behind Adams as he finished his profound and stirring 11-minute tribute to Parks.

In the press row at the back of Greater Grace Temple, I just chuckled quietly.

Not that I didn’t enjoy it, but because I’d heard it four years earlier, while Adams was presiding over esteemed Free Press editor Robert McGruder’s funeral services. Detroit City Councilman Coleman Young II says he first heard the speech in 1984, when Adams became president of the Detroit NAACP. Others say they heard it even earlier than that.

By 2005, the “thank ya” speech was his signature go-to spiritual place, the one every Black Baptist minister has in his back pocket for special moments. And there was no bigger stage than Rosa Parks’ funeral. His execution of the moment is still streamed on YouTube and the C-Span site.

Adams died last month. He was 86.

Yet, to remember him as a minister who said “thank ya” in multiple languages does not do his entire spiritually based prayer-turned mini-sermon any justice. It was one of the most profound segments of Parks’ hours-long funeral.

That’s what made Detroiters, even if we just knew Adams by reputation, feel some sort of way when hearing about his death, and why we’re still in mourning today, as we lay him to rest.

Not because of that singular moment, but the hundreds more we’re recalling in our minds now, whether a family member's homegoing service, a wedding, a NAACP Freedom Fund Dinner, a welcome before the Morehouse glee club concert, or a random Sunday service.

That’s what made Adams special: He never held back his prolific gifts as a preacher from those in his beloved city.

Charles Adams shared his gifts

For more than 50 years, Detroit was treated nearly each Sunday to the masterful teachings of one of the foremost Black Baptist preachers in America. His scholarly brilliance never went to waste.

Ebony Magazine twice named Adams one of the country’s top 15 greatest Black preachers, and one of the top 100 most influential Black Americans.

Growing up near Adams' home in Detroit's University District, he was Tara and Christian’s dad. He simply was the man who lived around the corner, who those of us in the neighborhood would greet after his hard day at work.

In some ways, he wasn’t much different than the other doctors, lawyers, engineers and educators living in the University District in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but Adams’ home seemed special.

It was — for God’s sake — the Rev. Adams.

His corner house on Fairfield and Clarita, always pristine, was his domain. In conversations with friends recently, we noted that we don’t remember seeing Adams ever cutting his lawn or landscaping. He had a lawn service, even then. It was understandable — he had too much work to do, in Detroit and throughout the country.

A force to be reckoned with

Thinking of Adams as someone whose work in Detroit happened solely in the pulpit does him no justice.

Adams was an ardent activist who sought to transform this city through economic development, a move unseen in Detroit at the time — yet it made him the forefather of what we consider the norm for mega churches now. Adams understood then Detroit’s fate was in the hands of its residents, and that the collection plate made churches accountable. His vision was to occupy land on Seven Mile near his church that was still vacant slightly more than a decade after the 1967 riots.

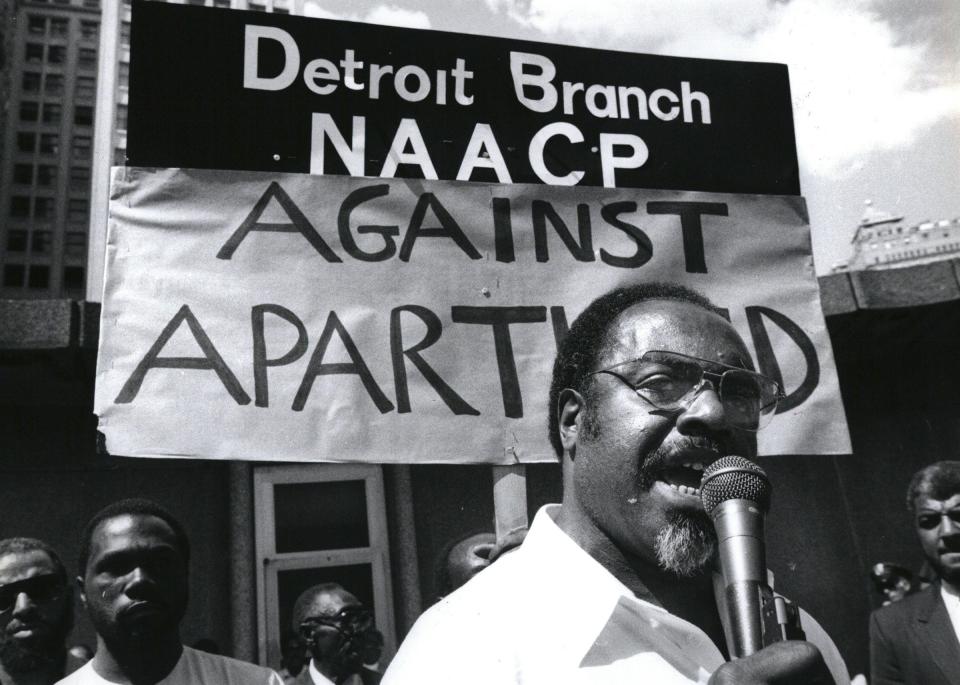

In 1984, Adams became president of the Detroit Branch of the NAACP, one of the largest and strongest in the country. During his time, Adams took on major community issues.

“Adams was a force to be reckoned with,” Detroit Branch NAACP President the Rev. Wendell Anthony said in a media release after his death. “Every politician wanted him on their side. Every adversary was concerned when he was not on their side. But for our community, Charles Adams was always on the side of justice, truth and equity of opportunity.”

In 1986, the Detroit NAACP led a boycott of Dearborn stores in opposition of an ordinance that kept nonresidents out of the suburb’s parks. The ordinance, passed by Dearborn voters in Nov. 1985, reminded Detroiters of the segregationist ways of Orville Hubbard, who served as mayor until 1977.

The issue was so racially charged that it hit the national pages of the New York Times and Los Angeles Times.

Activism and economic development

When the McDonald’s I used to frequent as a teenager opened, I never imagined the gravity of what was being done — a church owning local businesses and getting into economic development.

But Adams' vision of changing the landscape of the city was unheard of at the time. Now, we take for granted that when a mega church is built, with it will come housing and/or a retail component.

After the McDonald’s, the church acquired more land and built a Long John Silver’s, a Kentucky Fried Chicken and a Super KMart on Seven Mile and Meyers — a development I covered as a young reporter.

The church filled empty lots with businesses, and employed hundreds of Detroiters.

Still, every time I pass by the Kentucky Fried Chicken on the corner of Seven Mile and the Lodge Freeway, I’m reminded of the significance of that project.

Hartford fought for years to rid itself of a former strip club to purchase the land for the fast food restaurant.

It was gutsy, but Adams never ran away from a fight, or his convictions.

He cared for the young and the old alike. He was known to take the money raised for his church anniversary and donate it all to students in college. In 2017, the church opened Hartford Village, a gated senior citizens community.

Detroiters should not forget the man he was.

So that’s why today we may say our final farewells, but his works — here and throughout the nation — will never be forgotten.

That’s why I’ll simply say goodbye in the way the Rev. Charles Adams showed the world:

In France, they would say "au revoir."

In Spain, they would say "adios."

In Russia, they would say "dasvidaniya."

In Kenya, they would say "kwaheri."

But it doesn’t matter which way it’s said. Our farewells are in reverence of a man who labored on our behalf for decades.

His works shall forever live.

Darren A. Nichols is a contributing columnist at the Free Press. He can be reached at darren@dnick-media.com or his X handle @dnick12. Submit a letter to the editor at freep.com/letters.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Rev. Charles Adams' funeral starts today. He changed Detroit