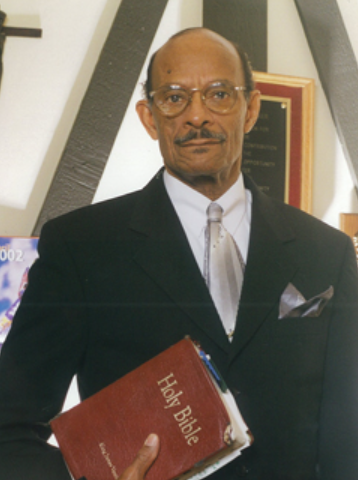

Rev. John Walker, leader in Colgate Divinity shutdown, dies at age 90

The Rev. John Walker's daughter, Sybil, was only 10 when he instilled in her a lesson about the world beyond herself ― a lesson that revolved around her love for hot chocolate.

She and her father were grocery shopping, and she wanted him to buy her favorite chocolate ― Nestlé ― for her to enjoy at home on a wintry day.

"Growing up I was a Nestlé Quik lover," she said. "All I wanted was Nestlé Quik." The year was 1974, and the Rev. Walker knew that the Nestlé company was one that invested in South Africa and its apartheid government. He explained to his daughter why he would not buy the product. She was 10, and not heard the term "apartheid."

"He tells me in the middle of the supermarket about apartheid and how we're not going to invest in that," said his daughter, Sybil Miller. "I, of course, did not agree with that."

But, later in life, she grew to appreciate the wisdom of her father, a local pastor and civil rights activist who died Dec. 28 at the age of 90.

"As I got older it was that kind of 'stick-to-it-ness' that I remember most about my father," said Miller, who now lives in Atlanta. "He would say, 'You may not always understand this now but you will.'

"... Whether I understood or not then, I did not get that Nestlés."

This was typical of the Rev. Walker, whether helping lead a sit-in at Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School for more Black faculty and more Black church history in its curriculum, or simply through his lessons from the pulpit. Whatever the issue ― whether it be the racism of a government thousands of miles and continents away or the bigotry in his home country and city ― Rev. Walker exuded a preternatural calm, a seeming serenity that made his incisive words all the more powerful.

Couple that with his ramrod-straight posture, perhaps a remnant of his years in the U.S. Army, and the Rev. Walker stood out in most rooms and most crowds.

"He had charisma," said the Rev. Lewis Stewart, a student of the Rev. Walker at Colgate Divinity and later a friend and colleague in local ministries. "He had this presence where people saw him as a mover and a shaker."

Said his daughter, Sybil: "My dad probably felt things on a (level) 10, but he never showed that. He figured out a long time ago that people listened better when you're not elevated because it's a learning opportunity."

The Colgate Divinity lockdown

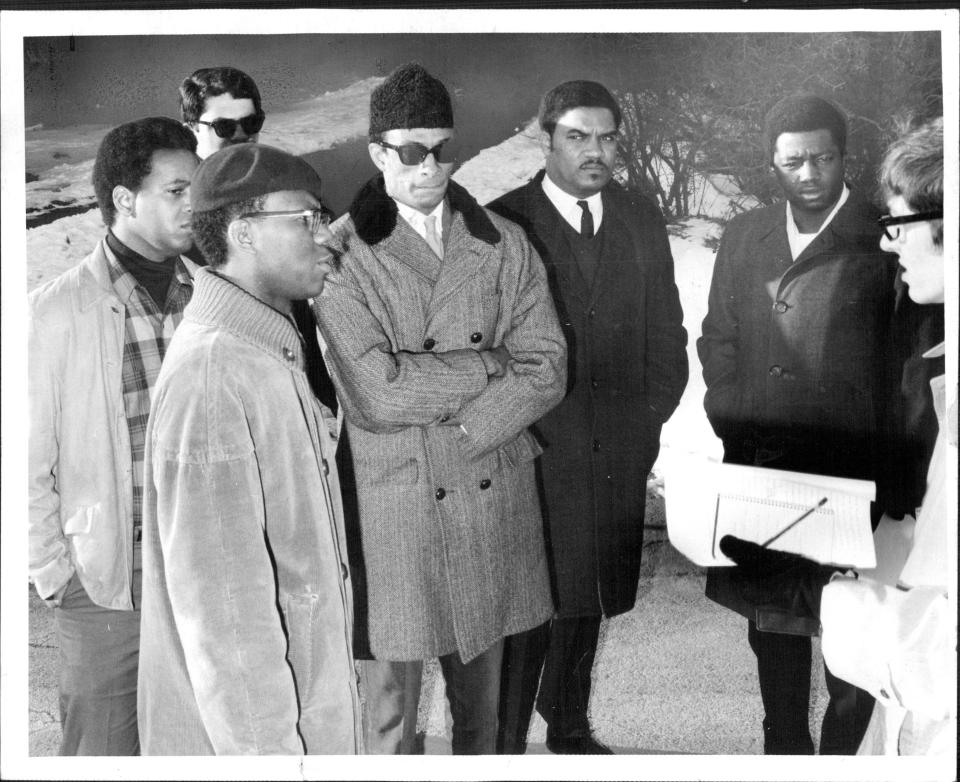

It was 1969 when the Rev. Walker, then a student at Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School, first made that presence known in Rochester. In the aftermath of the 1968 murder of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., he and other students formed the Black Student Caucus at the largely white campus.

As Democrat and Chronicle reporter Justin Murphy wrote of the caucus in 2018: "They demanded more Black representation in the faculty and board of trustees and the creation of a Black Church studies program. They brought Mahalia Jackson to town twice in one year and raised hundreds of thousands of dollars."

"The trustees said we were asking just a little too much too quickly," the Rev. Walker said in the 2018 article. "(But) we called them demands, not requests or recommendations. And that's when we decided to lock up the school."

For 19 days the caucus locked down the administration building. "The Black church represents the strongest opportunity to organize the masses of people behind issues which affect their lives," the Rev. Walker said in a 1980 interview with the Phyllis Wheatley Community Library. "I still maintain that."

Colgate was one stop on the Rev. Walker's ministerial journey. An Ohio native who served in the Army during the Korean War, he received his doctorate at Syracuse University, then returned to Rochester as a visiting lecturer and, in 1973, the director of the Baden Street Settlement Counseling Center. He was also intensely active with the local civil rights organization, FIGHT, initially an acronym for Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today. ("Integration" was later changed to "Independence.")

Social justice activism

The Rev. Walker was a persistent and powerful voice for equal rights and opportunity. In the 1980 interview, he said that he had seen little progress for Black people living in poverty in Rochester. Many were Southern transplants, he said, who had not integrated themselves into the political process and were often ignored by that process, even by leaders of color.

Even a push to better integrate the working ranks at Eastman Kodak Co. had been of questionable success, he said. The hope of the FIGHT organization and others was that the company would find jobs for the city's poor, when instead it recruited workers of color from outside the region to fill positions. Rev. Walker constantly pushed and prodded local institutions to do better.

Stewart said the Rev. Walker's work when young continued throughout his life, as did his scholarship.

"I came from out of a Pentecostal position but I didn't know much beyond Dr. King and that history of Black church involvement," Stewart said. "He opened up this whole intellectual and scholarly world for me and for others about the history of being Black in this country and the Black church being on the cusp of change for Black freedom."

Stewart once traveled to Little Rock with the Rev. Walker for a conference among Black people considering the formation of a separate political party.

"He spoke at that convention and people were so amazed by his grasp of history," Stewart said. "It was not only Black history but it was American history at the same time. It was world history also. All these things he synthesized into his presentation."

The Rev. Walker also had his own pulpit locally, serving as pastor of Christian Friendship Missionary Baptist Church in Henrietta. He assumed that role in 1989 and created multiple outreach ministries, including one at the local correctional facility.

He served as a leader in the former United Church Ministry, and the current United Christian Leadership Ministry ― both of them collaborations of Black churches to focus on social justice issues. Since the 1970s he was a proponent of more civilian oversight of the Rochester police, while still working hand-in-hand with police on some anti-violence and intervention programs, including how to alert families to sexual predators.

According to his family, he founded the Adolescent Pregnancy Program, the Rochester Anti-Apartheid Program, the Palestinian Resettlement Committee, the Malawian Hunger Project, the Swaziland Hunger Project, and the Freedom and Justice Program of South Africa. In addition, he taught history and political science at Monroe Community College for many years.

A jazz lover, the Rev. Walker wrote for the Black-run newspaper, Communicade, under the name Talik Abdul Basheer. He often referred to jazz as "Black Classical Music" and hosted radio shows on the topic.

Into his 80s, the Rev. Walker stayed active with diversity and inclusion programs.

"Whether being in a pulpit or in the classroom or even in a conversation, he was always a teacher," said Sybil Miller.

The Rev. Walker is survived by his wife, the Rev. Barbara (Lattimore) Walker; children, Sybil (Rodney, who is deceased) Miller, Burghardt (Ramona) Walker, Demeter (Chester) Walker-McGill, Sojourner (Mark) Williams, N’Djamena Walker, Asjiah Walker, Zion Walker, and Ericka Clarke; 13 grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Rev. John Walker, leader in Colgate Divinity shut-down, dies at age 90