Revealed: Full extent of Lord Mountbatten's role in '68 plot against Harold Wilson

Lord Mountbatten came dangerously close to leading a cabal of industrialists, generals and tycoons plotting a coup against an elected Labour government, a new book reveals.

The 1968 plot was designed to replace Prime Minister Harold Wilson with a coalition government to bring the country together, during what Mountbatten and the conspirators regarded as a time of national crisis.

According to a new biography of Mountbatten, Prince Charles’s great uncle and mentor, it took the intervention of the Queen to persuade him to cut his ties with the plotters rather than acting against Wilson, his Cabinet and Parliament.

Drawing on contemporary diaries of the period, historian Andrew Lownie reveals for the first time the full extent of Mountbatten’s involvement in the plot.

It came amid growing social upheaval, industrial unrest and economic decline, with demonstrations in central London against the Vietnam war, student occupations and increased trade union militancy leading to a belief among some in the establishment that society was disintegrating.

The industrialist Cecil King, chairman of the publishing giant IPC, began gathering senior figures around him who wanted to act.

He believed Wilson, who had been elected in 1964 and again in 1966, should be replaced by a ‘national government’ led by the likes of the pre-war fascist leader Oswald Mosley or a figure of the stature of Lord Mountbatten, who had overseen the withdrawal of Britain from newly independent India in 1947 and had recently retired as Chief of the Defence Staff.

Hugh Cudlipp, the editorial director of The Daily Mirror, told King in April 1968 that Mountbatten had said to him: “Important people, leaders of industry and others, approach me increasingly saying something must be done. Of course, I agree we can’t go on like this. But I am 67, and I’m a relative of the Queen. This is a job for younger men. Perhaps there should be something like the Emergency Committee I ran in India.”

On May 8 that year Mountbatten hosted King, Cudlipp and Sir Solly Zuckerman, the scientist and senior government advisor, at his Belgravia home in Kinnerton St, to discuss what to do about the Wilson government.

According to Cudlipp, Zuckerman expressed deep reservations about a possible coup, stating “This is rank treachery. All this talk of machine guns at street corners is appalling.”

Mountbatten appeared to some of those present to concur with Zuckerman and wrote of the meeting in his diary that evening: “Dangerous nonsense.”

Furthermore he stated in a letter to King in July 1970 that “my views are unaltered” and repeated Zuckerman’s warning that to remove Wilson was “rank treachery”.

However, the mystery of the aborted plot to remove Labour from power deepened when King later released his diary entry for the May 1968 meeting, which according to Mr Lownie’s book The Mountbattens, “gave a rather different account” of what was said.

King wrote that after Zuckerman left the meeting Mountbatten told him “morale in the armed forces had never been so low” and that the Queen “is desperately worried over the whole situation”.

According to King, Mountbatten “asked if I thought there was anything he should do”.

The book now reveals that in November 1975 Zuckerman - in what appears to be an attempt to set the historical record straight - added a crucial diary note to his own file on the May ‘68 meeting.

This stated: “All I hope is that Dickie [Mountbatten] did not go beyond what we had agreed. The fact of the matter is - as Hugh Cudlipp knows only too well - that Dickie was really intrigued by Cecil King’s suggestion that he should become the boss man of a ‘government’.”

Mr Lownie says in his book: “It was beginning to emerge that Mountbatten had shown far more interest than he, or the others, had earlier admitted.”

According to Cudlipp, Mountbatten had even compiled a list of names for a possible national government, including industrialists, senior military figures and civil servants, as well as ‘moderate’ Labour politicians.

Certainly Marcia Williams, Harold Wilson’s secretary and later Baroness Falkender, took the threat of a plot seriously, talking of Mountbatten “as a prime mover in the plan”.

In a conversation with members of the press following Wilson’s surprise resignation in March 1976, Baroness Falkender said: “Mountbatten had a map on the wall of his office showing how it could be done. Harold and I used to stand in the State Room at Number 10 and work out where they would put the guns.”

In the end what appears to have held Mountbatten back from supporting, or even leading, a coup was not any loyalty he may have felt to British Parliamentary democracy, but the influence of the Crown.

Mr Lownie cites Alex von Tunzelmann, the historian and scriptwriter, who - drawing on private information from Buckingham Palace - states: “It was not Solly Zuckerman who talked Mountbatten out of staging a coup and making himself President of Britain. It was the Queen herself.”

'Mountbatten longed to be prime minister'

Even before the Belgravia meeting it was clear Lord Mountbatten had long nurtured political ambitions at the highest level.

During a long conversation with Sir Solly Zuckerman in June 1946, while he was in Oxford to receive an honorary degree, Mountbatten - who had been Supreme Allied Commander of South East Asian during WWII before being appointed the last Viceroy of India - discussed what his post-war role might be.

He even suggested that he should by rights have been able to take the top job itself.

Zuckerman later wrote in his memoirs: “The one job that he felt that he could have done was that of Prime Minister, but that office had been closed down to him because of his royal connections. He talked as if there was nothing he could not do.”

The following year Orme Sargent, the then Permanent Under-secretary at the Foreign Office, confided his fears about Mountbatten’s dictatorial ambitions to the journalist Robert Bruce Lockhart.

Further evidence of Mountbatten’s political aspirations emerged a few years later.

In his book Six Men Out of the Ordinary, Zuckerman writes how in 1951, at a cocktail party at Admiralty House, Mountbatten, who was killed when the IRA blew up his yacht in 1979, began to bemoan “the sorry state of the country”.

Zuckerman writes: “Dickie was immensely worried, and I was not surprised when he again said that with all his political experience, he might have made a better job of leading the country than had Attlee [the first Labour Prime Minister, elected in a landslide in 1945].

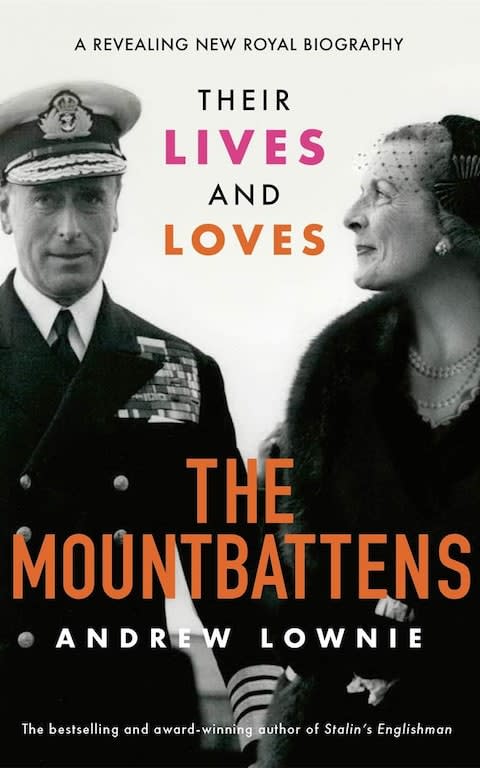

The Mountbattens – Their Lives And Loves by Andrew Lownie (Blink Publishing) is out 22nd August. Visit http://www.themountbattens.com/