Review: 2 die at confluence of race, disinformation and guns

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

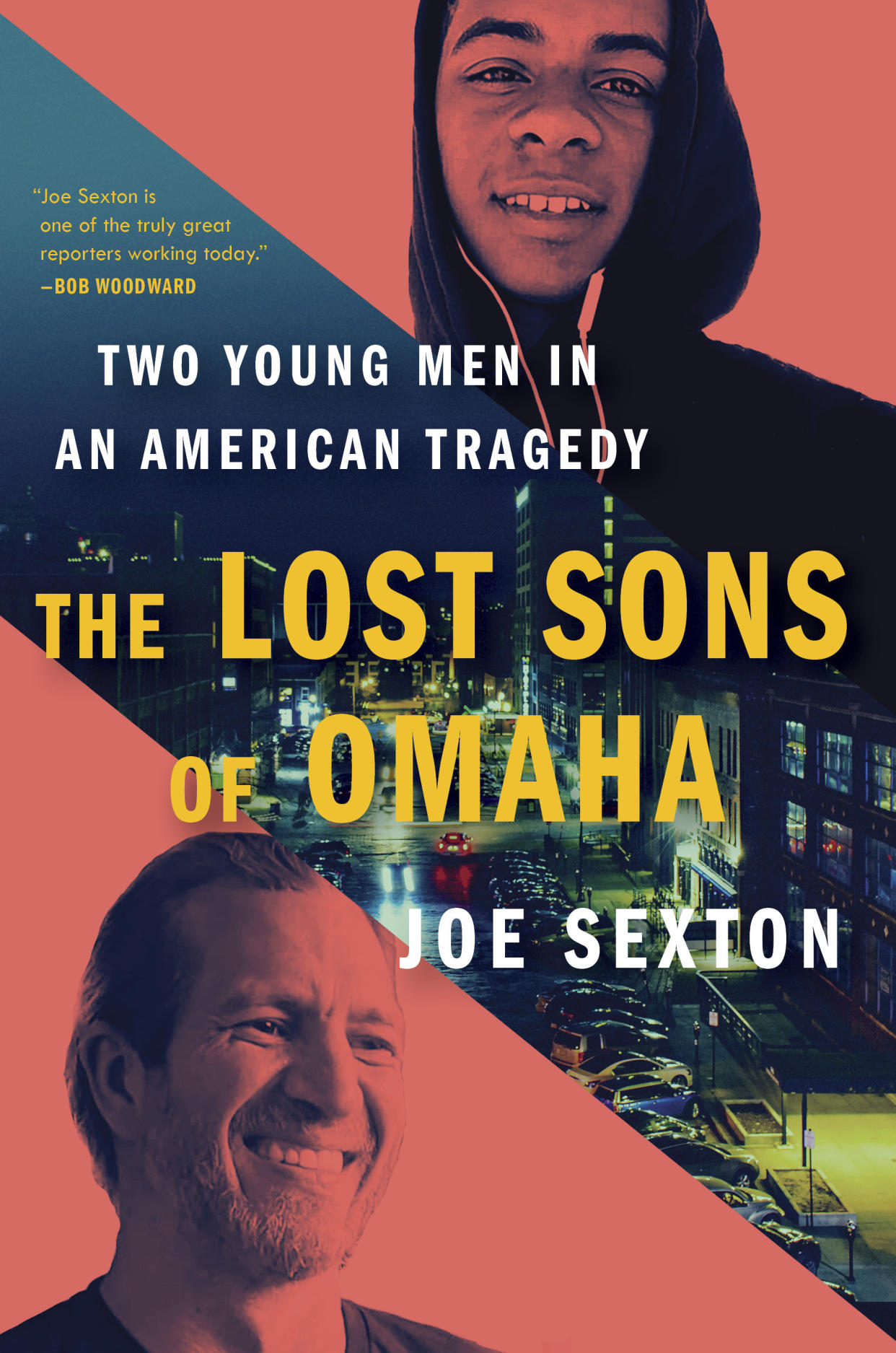

“The Lost Sons of Omaha: Two Young Men in an American Tragedy,” by Joe Sexton (Scribner)

At the intersection of racial tension, economic disparity, social media misinformation and guns, two sons of Omaha died in a made-in-America tragedy in 2020. James Scurlock and Jake Gardner’s lives collided as part of a national unraveling following the death of George Floyd, a Black man, after a white Minneapolis police officer knelt on Floyd’s neck until he could no longer breathe.

Scurlock, a new dad, was not thinking like one on that May 30, the third day of upheaval following Floyd’s death. Video shows him trashing an architecture office near Jake Gardner’s nightclub in the city’s Old Market district.

Gardener was a white Marine veteran of Iraq and had returned to his hometown and opened the bar, which had sustained sharp losses when COVID-19 broke out. Now, the streets of Omaha and other American cities were convulsing with Black Lives Matter protests.

Into that arena, Gardner appeared with a gun to protect his bar from further damage. But realization that Gardner was armed further inflamed the crowd milling along the street.

A woman jumped on Gardner’s back, and then Scurlock. Gardner fired over his shoulder after Scurlock wrapped Gardner in a chokehold.

In deciding against filing charges against Gardner, Douglas County Attorney Don Kleine showed video of the scene and explained how he had concluded that Gardner acted in self-defense.

But to many in Omaha’s Black community, Kleine’s detailed explanation didn’t matter.

As Ja Keen Fox, an Omaha Black activist noted, Blacks were combatting what they saw as “white supremacy and racism.”

And, as Joe Sexton writes in “The Lost Sons of Omaha,” false narratives were emerging and gaining momentum with “extraordinary speed” — that Gardner was a Nazi sympathizer, a psychopath, homophobic and had premeditated the murder of Scurlock.

In the rising heat of social media, the county appointed a special prosecutor; months later, a grand jury indicted Gardner for manslaughter.

Gardner told family and friends he would end up bankrupting his family defending himself and would not survive prison.

He shot himself to death.

Sexton has crafted a meticulously researched and briskly written account that deftly weaves the influences of racial injustice, economic disparity, incendiary social media and guns.

It’s hard to read “Lost Sons” though and not feel an overwhelming sadness — not just for the loss of Scurlock and Gardner but for an America that seems to have lost its moorings — failing to embrace the multi-ethnic society that we are, succumbing to fiction presented as truth and regarding guns as our ultimate settlement.

If it were not for swirling false social media assertions and if Gardner had not tucked a gun into his waistband that fateful night, both men likely would be alive today, bruised and angry but perhaps able to discuss why Blacks see our justice system so differently than whites.