Review: Was Andy Warhol a saint or scourge, genius or dolt? A new biography befits a great life

Andy Warhol, circa 1960, had a problem. Thanks to his success as a commercial artist, he had built up an extravagant lifestyle. He owned an angel-blue Upper East Side townhouse and the tastes to match, but he was no longer winning the big contracts.

Imagine a semi-closeted gay man in New York City logging hours for The Man during the day while working quietly, steadily, at night, trying to create the next vanguard of American painting. You’re actually imagining Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg. Warhol wanted to be that person, desperately, but in his off hours he’d been making negligible drawings.

Art, circa 1960, also had a problem. How do you move painting away from abstraction while also moving it forward? Pop artists — Johns, Lichtenstein, Rosenquist — solved this problem by becoming landscape painters. The American landscape, however, was no longer made up of trees and cows lowing plangently at dusk. It was Dick Tracy, roadside billboards and packaged goods.

With his Campbell’s Soup can paintings, exhibited in Los Angeles in 1962, Warhol was not pioneering anything new. He was merely upping the ante. More than Johns or Lichtenstein, Warhol concealed his own expressive capacity, burying it so deep that any evidence of the sensibility of the artist all but disappeared. You can look at a soup can and wonder at how familiarity, intimacy, warmth, even feelings of love might attach to an inert object, just as you can look at a painting of Marilyn, Liz or Elvis and wonder at how cold, inert, even alien the human form had become. One can say all kinds of things about the work but its power lies, finally, in its horrible silence. And what lies behind that?

Was this man a scourge, capitalism’s most joyous co-conspirator? A satyr, a saint, a sage? Was he a conniving strategist? Or a dim bulb?

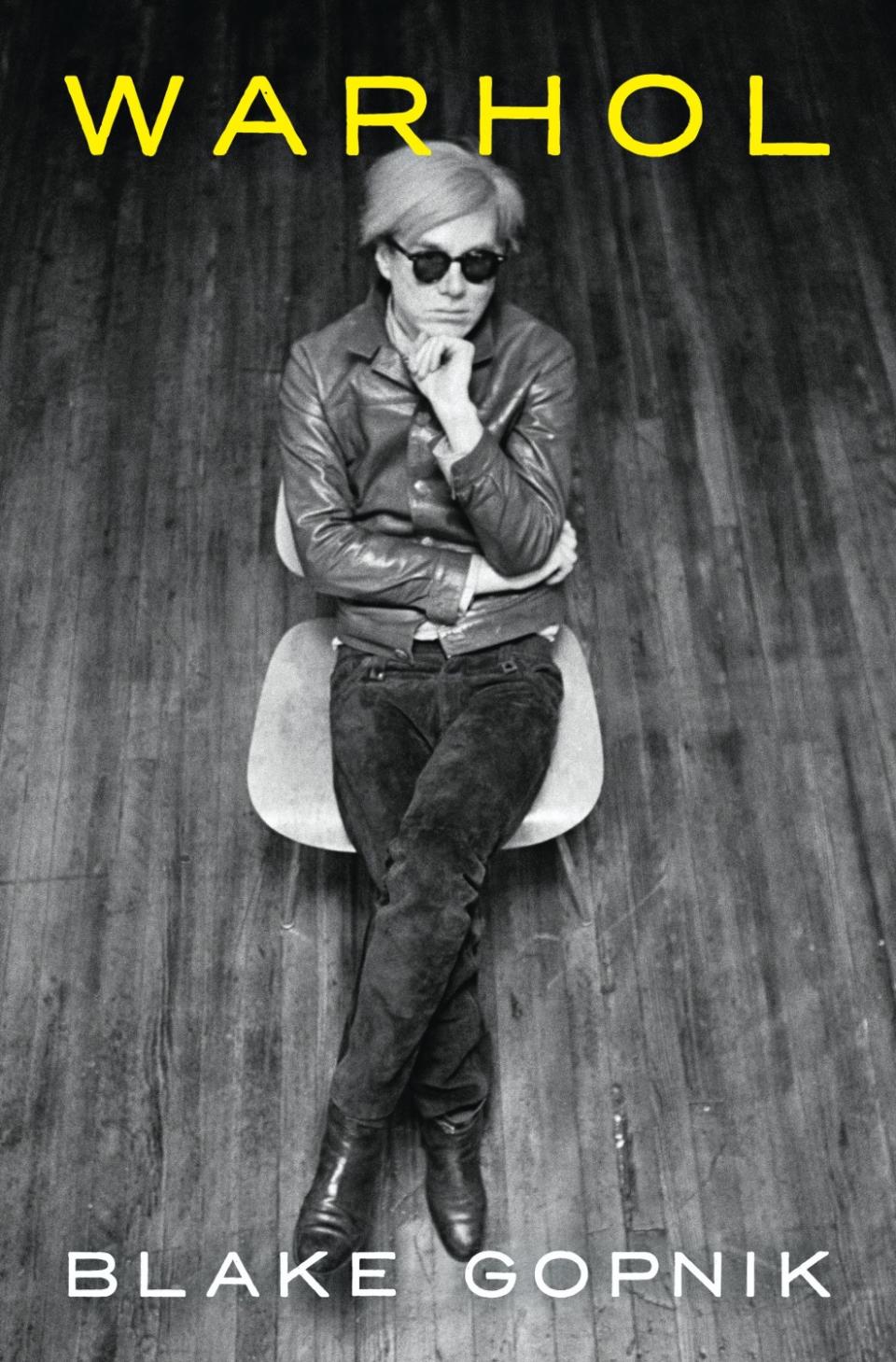

Warhol lived one of the great lives of the 20th century, and he now has a biography worthy of that life. For “Warhol,” Blake Gopnik interviewed hundreds of eyewitnesses and scrutinized every paper trail, down to the artist’s ticket stub for “Cats.” Even at 976 pages, the book rarely leaves you wanting less. It turns out this life, so often discussed in grandiose or mythic terms, is quite intricate, even beautiful, in extreme close-up.

There is Julia Warhola, Andy’s mother, crafting peach tins into the shape of flowers and selling them door to door; actor Dennis Hopper, among the first to “get” Warhol, jumping up and down upon seeing his first soup can; Andy himself, older, mellowed, in a Santa beard, ringing the bell for the Salvation Army. (He lasted 45 minutes.) In this textured portrait of an artist of annihilating smoothness, Gopnik has finely rendered many of Warhol’s milieus. Perhaps most endearing is the intricate social geography of gay New York in the 1940s and ’50s.

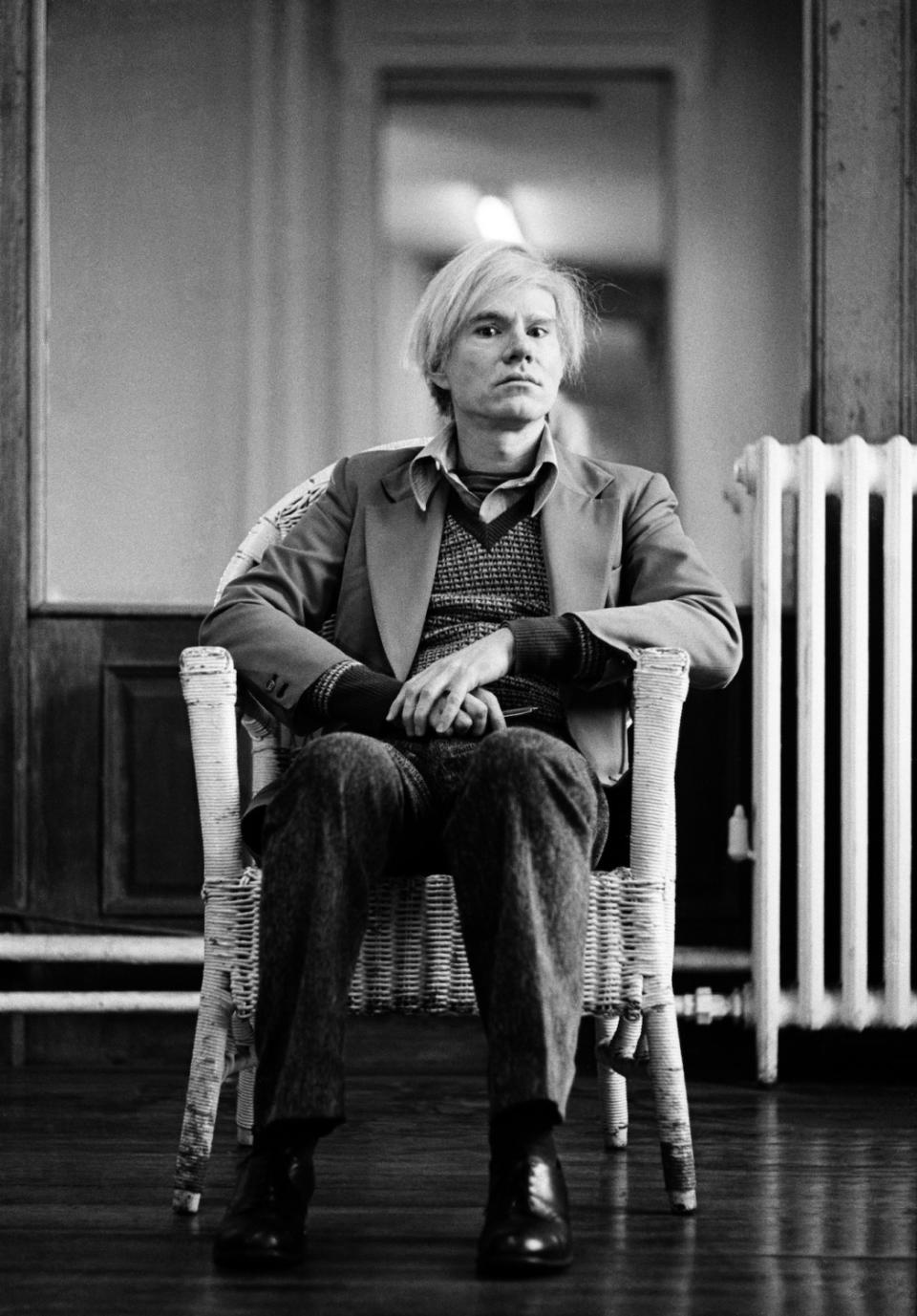

The Warhol of this period has been romanticized as the quintessential urban loner. In fact, Gopnik makes clear, he was a gregarious, well-liked man, surrounded by a fairly ordinary roster of friends and lovers. He was excluded, however, from the art world, which must have cut him deeply. Warhol graduated from the Carnegie Institute expecting to be a fine as well as a commercial artist, but even after he’d abandoned his homoerotic drawings, the major New York gallerists continued to shun him. Leo Castelli found Warhol the person too weird for his tastes, and worried his comic strip imagery was too close to Lichtenstein, whom he already represented.

So Warhol did the unthinkable. He debuted the soup cans in L.A. The show earned his first round of press coverage. Castelli did eventually sign Warhol, but almost none of his best work showed under the dealer’s auspices. The biggest revelation in “Warhol” is how minor a role the art establishment played in forming his reputation. As late as the early ’80s, Warhol could still bemoan how his prices lagged those of Johns and Rauschenberg, and how MOMA had acquired only one of his paintings. (“The little Marilyn. I hate that.”) So — how did he do it?

The quick and very Warholian answer is that he used the power of celebrity. A slower, more careful one is that Warhol shrewdly pitted the Scene against the Institution. And by 1962, modern art was an Institution. In America this meant MOMA, the Jewish Museum, the Met, Castelli. The Scene, meanwhile, was the Factory. The Factory was not just a space where Warhol made art and freeloaders cavorted. It became one of the super-symbolic youthquake It Places of the 1960s.

The Factory was a porous, chaotic arena for scene-making, drawing in exhibitionists, druggies, socialites, rock stars, movie stars, Ivy Leaguers and, most critically, journalists. By the mid-’60s, Time magazine, et al., were hypnotized by this beguiling apostle of desublimation, the Pan figure holding the keys to a secret kingdom called “the underground.”

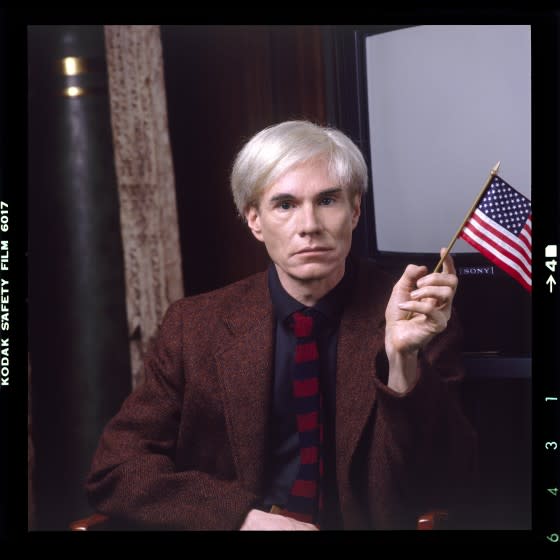

As his art was being turned into a succès de scandale by the gullible press, Warhol began cultivating a public image, one that had little to do with the manner and style of “Raggedy Andy,” the whimsical oddball he’d been since his student days. This new Warhol was leather-clad and hard and, in his way, as horribly silent as the canvases. When he wasn’t merely blank, he was a master of the evasive put-on, the non-answer, the deadpan stammer. (Or simple lie.) He was withdrawing from his manner exactly what was missing in his paintings: affect.

Affect lies in the cadence of our speech, the arrangement of our features, the quality of our laughter. The absence in Warhol is startling; it’s what gives everything he did and touched its radical aura. With his new personal style, Warhol was breaking down any distinction between affect and affectation. The sphinx act drove onlookers wild, until they asked of Warhol the same question they’d asked of the Factory: What is going on inside there?

Warhol exiled people when they bored him; he weaponized his lack of affect as beautifully and efficiently in his relations as he had in his art. He became a genius at making the elect feel caught up in a daring enterprise while provoking in others the special torment he himself knew so well — the feeling of being left out.

Warhol was attached to spaces whose fascination lay in their powers of exclusion: the back room of Max’s Kansas City; Studio 54; the Limelight. Maybe it’s just blunt-force human nature, that the more something excludes you, the more you want in. This is Groucho Marx, inverted and intensified, and the formula applies not only to the Factory but to its buttoned-up sequel. When Warhol pivoted, on a dime, away from the madness, and moved his headquarters to Union Square, he dropped the Factory name and instituted a dress code but nonetheless kept a spatial arrangement designed to highlight degrees of insiderism.

The target wasn’t the press anymore but high-paying clients for his new line of business, society portraiture. Warhol was not the first serious artist to care about money, but he was the first to make a shameless love of it central to his vocation. By rendering up his underground cred to the principles of entrepreneurship, he was not only prophesying the future; he was modeling behavior. The new “studio” was a small, nimble, eat-what-you-kill workplace, organized around the highly branded talents of a single visionary individual.

Was the change so shocking? The single consistent thing about Warhol, from 1960 until the day he died, was his utter refusal to conceive of human beings in the usual way — which is to say as interior, subjective, reflective, self-fashioning, suffering and ethical creatures. This refusal often felt like a lark but, from the evidence gathered by Gopnik, his shallowness lay deeper than that; it went all the way down. Into the era of the yuppie, the fundamental Warholian project was kept intact: to maximize creative autonomy while minimizing human subjectivity, until the former can be said to describe anything you do and the latter all but disappears.

In “Portrait of Andy Warhol,” a painting by Julian Schnabel, Warhol stands against a black-velvet void, naked and exposed but for a pink girdle, which is pulled excruciatingly tight. He looks like an El Greco saint, with hints of a Francis Bacon messiah. The girdle was a medical necessity, thanks to Valerie Solanas’ botched assassination attempt in 1968. In spite of what you made of yourself, I see you as you are, the canvas seems to say, by way of reconnecting Warhol to a tradition of expressivity and suffering — to art history, as it existed before Warhol did his level best to obliterate it.

Warhol won that one, didn’t he? Gopnik promotes a Great Man theory of the case: Warhol was an epochal genius who deserves his place on the “top peak of Parnassus, beside Michelangelo and Rembrandt.” In effect, Gopnik has written two books. The first is an exhaustively researched and definitive account of the life. The second is a series of apologies and excuses for a tax cheat, voyeur-sadist, bad son, skinflint, publicity hound, social climber, shopaholic. Some small-bore skepticism along the way might have helped make the canonical judgment more credible.

We inherit Warhol, circa 2020, not just as an artist but as a climate of feeling — a climate that can easily be confused with reality itself. Paradigms never shift back, precisely, but they do shift again, and fickly. As we come to see Warholism as part of a second Gilded Age, one the pandemic may finally kill off, his reputation will change, and in unexpected ways. Maybe, in the most Warholian gesture of all, the work contains within it the seeds of its own destruction. Rendering Warholism unfashionable, by its own logic, is the same thing as killing it. At that point the artist, once an unrivaled colossus, would fade into an absolute silence, which was, after all, his real medium all along.

Metcalf is the cohost of Slate’s “Culture Gabfest” podcast and is writing a book about the 1980s.

Warhol

Blake Gopnik

Ecco: 976 pages, $45