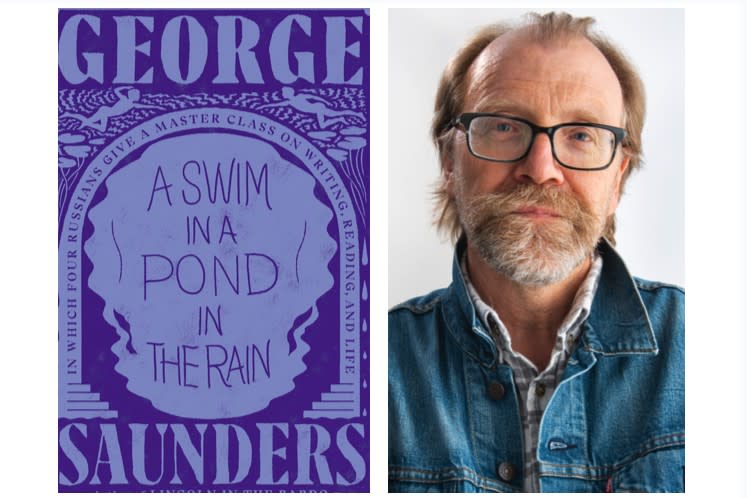

Review: If anyone can teach you writing, maybe George Saunders can?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

About a decade back, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Colson Whitehead had a nice sideline poking fun at people who make pronouncements about good writing. In a speech, he caricatured the plummy, officious critic delivering high-toned statements of the obvious. (“When we see a word, we must ask ourselves foremost, ‘What does it mean?’”) In an essay, he mocked the platitudes that infest most lists of writing rules. (“In many classic short stories, the real action occurs in the silences. Try to keep all the good stuff off the page.”) Point being: Successful fiction is too slippery and complex to be reduced to how-to lists.

George Saunders, also a celebrated fiction writer with an excellent sense of humor, grasps the problem — but not so much that he can resist his own contribution to genre. In his quirky new writing guide, “A Swim in a Pond in the Rain,” he implores, “God save us from manifestos, even mine… The closest thing to a method I have to offer is this: go forth and do what you please.”

He saves that bit for the end (spoiler alert), but from the start, Saunders recognizes the tension inherent to any book about writing: No one system can define successful writing, yet any book on the subject is obligated to propose some kind of process for it. That may explain why so many of the best-loved guides feel self-contradictory. Annie Dillard’s “The Writing Life” makes the job seem like meditative agony; Stephen King’s “On Writing” pitches it as pragmatic dreaming. Because the task is impossible, craft books tend to read like invitations to a kind of shared suffering.

But if Saunders’ writing guide is no more helpful, it’s funnier and more open-hearted. (Indeed, it evokes his book “Congratulations, by the Way,” a graduation speech — another prescriptive genre that’s all but impossible to get right.) And it helps that he’s called in reinforcements. While most such guides offer only excerpts from the good writing you’re shooting for, Saunders includes the full text of seven short stories by four Russian authors: Turgenev, Chekhov, Tolstoy and Gogol. So even if “Swim” fails you, you have a solid anthology of engrossing, gloomy and peculiar classic fiction.

“Swim” is based on a class Saunders has taught for 20 years at Syracuse University’s top-ranked MFA program, and though he approaches the book with I’m-just-winging-it humility, he works in some pedagogy. His trick, pace Whitehead, is not to be so pedagogical about it. Rather than throw down diktats about plot, structure and characterization, he encourages readers simply to walk attentively through each story. Saunders invents shorthand to make the process less intimidating: the acronym TICHN (“things I couldn’t help noticing”) or “ritual banality avoidance.” Though cutesy, it eases that tension, staking out a middle ground between grand generalizations and fussy sentence parsing.

The Russian stories are surprisingly amenable to this kind of work. The rhythmically repeated romantic failures in Chekhov’s “The Darling” let Saunders riff on structure; the tragic ironies of Tolstoy’s “Master and Man” highlight plot and character; Gogol’s “The Nose” is a clinic on how the absurd illuminates reality. Saunders delivers some old-fashioned from-the-lectern close readings, with occasional forays into multiple translations to explicate certain word choices. But he bites off bigger chunks than an academic, likelier to scrutinize paragraphs than lines, pulling out slabs of text to underscore a thought about how the Russians achieved their emotional effects.

For instance, he admires Turgenev’s “The Singers,” despite its flaws: needless exposition, clunky structure, an obvious turn. (Yashka, the “best” singer in the story’s central competition, isn’t the most technically accomplished.) The tale is stuffed with tensions at a more subtle level that make its climax, however anticipated, shine. “Like Yashka, the writer has to risk a cracking voice and surrender to his actual power, his doubts notwithstanding,” Saunders advises.

It’s persuasive in context. But with lines like that, Saunders opens up the kinds of questions that defy answers, even if you have a Booker Prize, a MacArthur "genius" grant and a rack of National Magazine Awards. When do you take a risk and when do you stick to the rules? When do you get to make messes and when is it best to avoid them?

On such points, Saunders may be more honest than most writing teachers, but it’s where “Swim” is at its haziest. “That’s all poetry is, really: something odd, coming out,” he writes. (Thanks. Now what?) “When I was a kid, Lipton had a TV commercial with the catchphrase ‘Is it soup yet?’” he writes. “We’re always asking of a work we’re reading (even if it’s one of our own): ‘Is it story yet?’” (That wouldn’t feel out of place in one of Whitehead’s bits.)

But if the only solution is for writers to figure it out for themselves, Saunders excels at motivating them to do the figuring. Recalling his own early stumbles, he describes how his overly careful and mannered apprentice work eventually gave way to the goofball riffs that informed his first story collection, 1996’s “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline.” It’s a magical moment — George Saunders became George Saunders! — but one defined by unteachable randomness. “It was as if I’d sent the hunting dog that was my talent out across a meadow to fetch a magnificent pheasant and it had brought back, let’s say, the lower half of a Barbie doll,” he writes.

If you want more practical help than that, Saunders provides some exercises in the appendixes. Will any of them make you a better writer? Only time solves that problem. (MFA programs advertise their famous faculty, as if you might acquire brilliance by osmosis, but read any interview with a debut novelist fresh from the workshop and the main virtue is clear: Time to write.) Being a good reader and writer, for Saunders, is a way of living well; it’s a firewall against “people with agendas, trying to persuade us to act on their behalf (spend on their behalf, fight and die on their behalf, oppress others on their behalf).” Living well is tough. How could writing well be any easier?

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.