Review: Forget about 'immersive' Van Gogh. Pipilotti Rist's MOCA show is the real thing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Near the entrance to “Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor,” newly opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Little Tokyo warehouse space, a slew of projected videos accomplishes something rare. Digital ephemera gets physical, gaining material heft, more like a solid sculpture than usually vaporous video art.

Rist has built the rear façade of a two-story clapboard house on one tall wall of the dimly lighted gallery, with picnic tables scattered about as if they’re out in a big backyard. Brightly colored video projections swirl across the floor, while others shine in the home’s five windows.

To get to the shutter-framed windows to see what’s going on, I found myself walking gingerly across the indoor/outdoor room. It was as if I might trip and stumble over the flickering light of an image projected onto the floor.

Which is nuts, I know. All that’s there is colored light.

But that disconcerting experience, unconsciously felt in the body, is central to the Swiss artist’s eccentric work, which unfolds in an enchanting survey of her video, sculpture and installation art drawn from the last 35 years. The show, postponed more than a year by the pandemic, was worth the wait.

Before video art ever existed, painter Ad Reinhardt once famously warned that sculpture is something you bump into when you back up to look at a painting. Here, video imagery is something you bump into when you try to figure out where you are as you find your way home. Given today’s ubiquity of such always insubstantial but sometimes commanding pictures skittering across countless screens — phone, TV, desktop monitor, laptop, tablet — this is no insignificant feat.

This ethos began to emerge in a powerful way in the two-channel video shown at the 1997 Venice Biennale that made Rist, then 34, an international sensation. The video, “Ever Is Over All,” is projected into a corner, covering two large adjoining walls.

The image on one side is a skewed view of nature — a field or garden full of red-hot poker plants, their spiky crimson and yellow flowers shown in human-size close-up, pressed against the picture plane. On the other, a bubbly young woman wearing a flowing blue party dress and ruby-red slippers — Dorothy Gale as glossy fashion model — strides in slow motion down the sidewalk of an urban Oz.

Clutching a metal version of the red-hot poker flower, she cheerfully raises it overhead, swings and shatters the side windows of cars parked along the street. Crash! (Laughter.) Smash! (Whoop.) A passing female beat cop gives the jaunty vandal an equally jolly smile, and even a tip of the cap.

The installation has long been admired for its jubilant, feminist-inflected defiance of institutionalized norms. (Almost 20 years later, Beyoncé riffed on it in her 2016 music video for “Hold Up.”) Only in a choreographed work of art could such freewheeling destructive fun exist as a constructive anthem.

In the context of the exhibition, though, what is emphasized is its upending of the one-step-removed quality of experiencing digital pictures, trapped behind glass. Familiar with sitting in a car as a passenger looking at the world out the window, experiencing life through a screen? Crash! Smash!

Rist also takes on the corporate dullness and bland commercial manipulation of most digital imagery, chiefly by putting privacy and intimacy on a public pedestal inside a museum. In the first gallery, the vivid videos brightly playing in the windows of her house — so close up as to make them into blazingly colored abstractions — pull you over to see what’s happening. A viewer is unobtrusively seduced into being what amounts to a Peeping Tom, peering into a stranger’s windows.

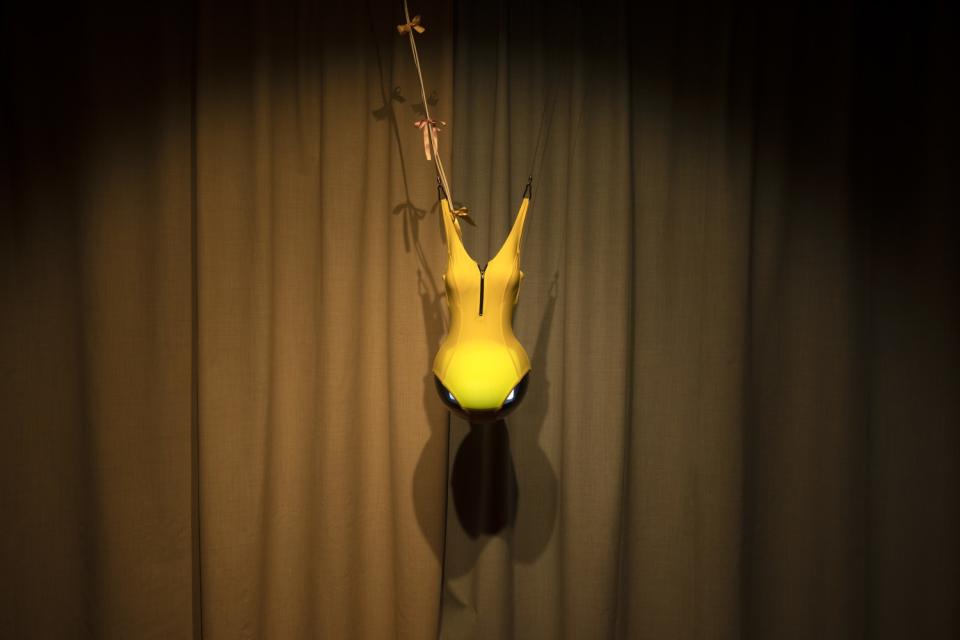

Nearby, down a dim and curtained corridor, a woman’s spotlighted swimsuit in sunshiny yellow is suspended from the ceiling. Cradled inside is a spherical TV monitor roughly the size of a basketball. The swelling feminine form suggests a pregnancy in a womb, video technology represented as a mysterious, growing creative force.

A sticker on the floor exhorts: “Think louder.”

So, it could refer to a medical camera probe into the body — a common enough practice these days. To make out the flickering image playing on the monitor’s curved screen, which might have an answer, it’s necessary to get up close and peer into the swimsuit’s leg holes. Performing an intrusive inspection of a crotch is at once disturbing, funny and puzzling in its effortless dissection of video’s seductive power.

These and related themes recur throughout the show. One room features lounging pillows on the floor, a place to relax and take in the gigantic, vertiginous video projections on adjacent walls. Sensual touch is repeatedly pictured — fingers playing with leaves, giant wiggling toes, naked bodies rolling in grass, apples tossed on the ground and grabbed by a snorting pig — woozy images that loosely recall the fall from grace in the Garden of Eden, here likened to the knowledge avalanche that digital images have provided.

The “Pixel Forest Transformer,” a room filled with strings of chunky, flickering LED lights hanging from the darkened ceiling, evokes neurons enlivened by electrical impulses flashing in the brain. (A hidden media player changes the colors of the LEDs.) Walking among them is like being inside a video screen surrounded by digital pixels. Some are revealed to have long, squiggly tails — spermatozoa, perhaps, which resonate against the labial form that Rist designed for the lights.

Above the museum’s front desk, the nine tiers of a big chandelier in the form of a globe are lined with hanging underpants. It’s like used unmentionables in the wash hung out to dry. The layered globe nods in the direction of a famous Modernist object — Danish designer Poul Henningsen’s 1958 “artichoke” pendant lamp — then undercuts its dignified public aura with a laugh-out-loud funny dose of down-home intimacy.

References to other art are common in Rist’s work, where art comes from other art. The “Pixel Forest Transformer,” for one, recalls the boxed mirror environments of American artist Lucas Samaras and Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama.

“The Innocent Collection,” a white wall covered in white plastic, paper and plastic foam objects — plates, packing material, coffee cups, toilet paper tubes, an apron, etc., all donated by MOCA employees — crosses two predecessors. Kazimir Malevich’s “Suprematist Composition: White on White,” a spiritually radical abstract painting from the anything-is-possible aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution, mates with the found flotsam of British artist Tony Cragg’s 1980s wall sculptures made from plastic trash washed up on the beach.

Occasionally the references overwhelm Rist’s work. “The Innocent Collection” feels thin, not adding much to the sources.

For “Das Zimmer (The Room),” a hugely oversized living room set invites visitors to climb onto an enormous sofa or side chair and curl up to watch her videos on an impossibly small TV monitor. Making us all into a Lily Tomlin-like Edith Ann is merely amusing; the imaginative child wonder provided by a work such as Robert Therrien’s giant sculpture of a table and chairs, made the same year (1994), casts a more expansive shadow.

Appropriation, whether from popular culture or art culture, can be tricky to execute in a compelling way. Most often Rist's cross-referencing makes for a trippy success story.

MOCA curator Anna Katz and curatorial assistant Karlyn Olvido have worked with the artist to transform the sprawling space inside the Geffen Contemporary into Pipilotti’s Playhouse. (Surely Pee-wee Herman would be proud.) The show's planned run, nearly nine months (closing June 6), is far too long; but, the emergence from a cloistered pandemic, where screen life has been further exaggerated, couldn't be better enhanced. The only thing missing from this generous psychedelic excursion through the digital looking glass is a selection of cannabis edibles in the museum shop.

Forget those frankly absurd “immersive” Van Gogh or Monet commercial events lately turning up in empty storefronts across the land. They exploit rather than illuminate the contemporary digital predicament. A bunch of high-resolution slides of famous, hundred-year-old paintings being projected on surrounding walls at an admission price of 55 bucks is simply no match for lounging on a floor pillow to be welcomed into Rist’s eye-popping video garden of electronic Eden. Actual art by a gifted artist is better than reproductions of art sold by a corporation any day — especially at one-third the price.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.